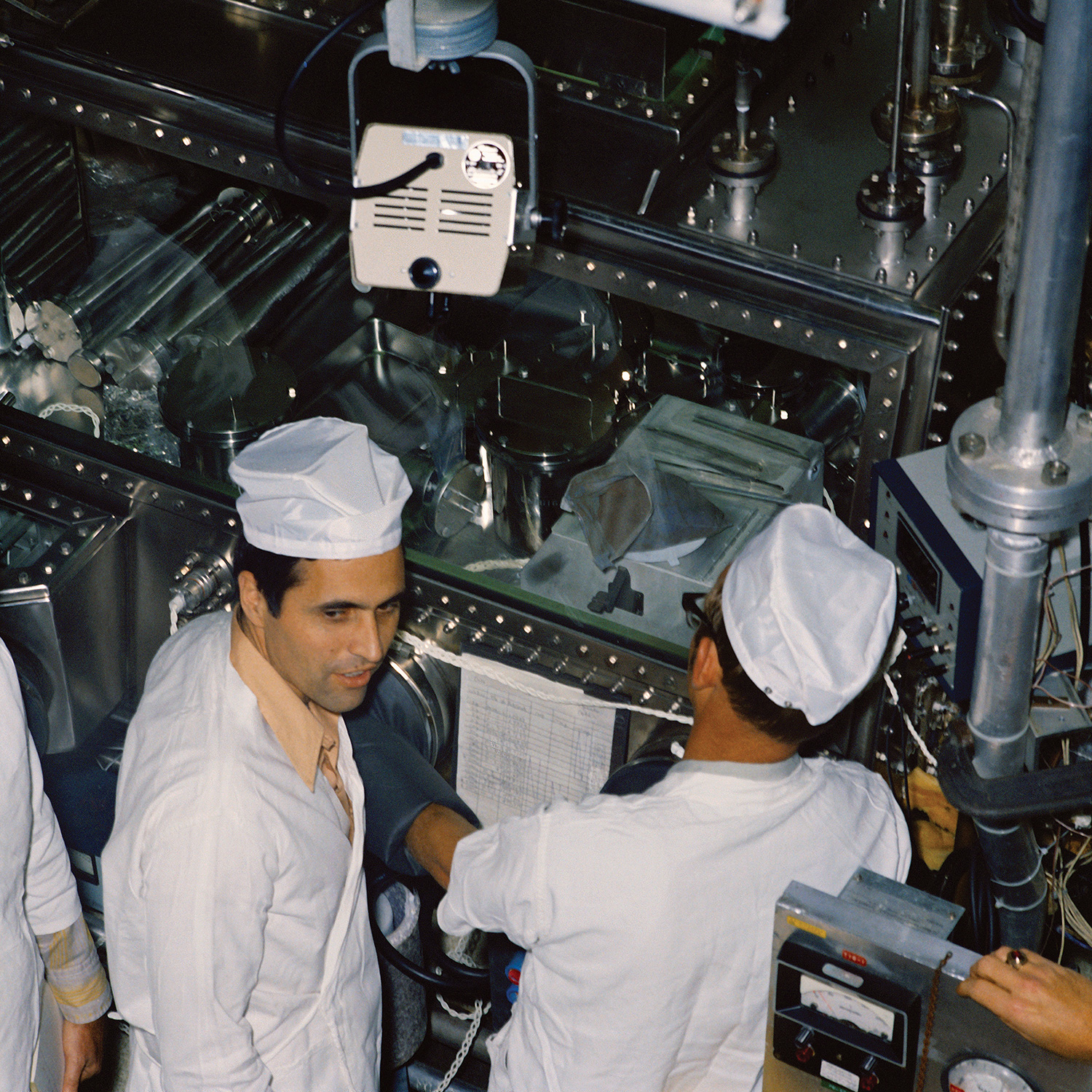

Of the 12 men who explored the Moon, only Dr. Harrison ‘Jack’ Schmitt was a professional geologist. After years spent training those who had gone before him, he blazed a trail for the scientist-astronauts who would later follow him into space.

Schmitt: “Well I think it was important to the space program because it set the stage for scientists and engineers who were not trained in the military, and indeed many of them who were not pilots, to participate in Skylab and Space Shuttle and the International Space Station.

“Now from a pragmatic point of view, that is the important thing, but it also illustrated that whatever you are going to do in space, you want to send people who are professionally expert in a particular field that is important, and that has been, more or less. If you are going to do field exploration on the Moon, the most likely person to do that, the best is a trained field geologist. And in the Apollo program that person also had to be a trained pilot.”

While Schmitt did receive pilot training through the military while serving as a civilian astronaut, the experience of exploring the Moon presented other obstacles to overcome once on the surface.

Schmitt: “Well, the main difference in my experience is the time constraint. We had a certain amount of time on the Moon, and we only had a certain amount of time outside the spacecraft for any given day. And then, of course, added to that is the physical constraint of operating in a space suit.”

“Now there are some environments on Earth where some or all of those constraints exist one way or another, but in my experience, I felt much more time pressure and physical limitation pressure than in other activities I’ve felt here on Earth.

Despite the fact that five other lunar missions had been conducted, Schmitt went to the Moon prepared to be surprised.

Schmitt: “I think in the field, when you go into a new area, you have to assume that everything you see, that is new and no body else has seen before, is a surprise. But you go into the field with working hypotheses, hopefully several, to test, and sometimes it pans out that one or the other hypotheses explain what you ultimately see. And other times you have to come up with entirely new hypotheses because of what you have found.

“And the Moon was no different than my work in Norway or Alaska or Montana or other places.”

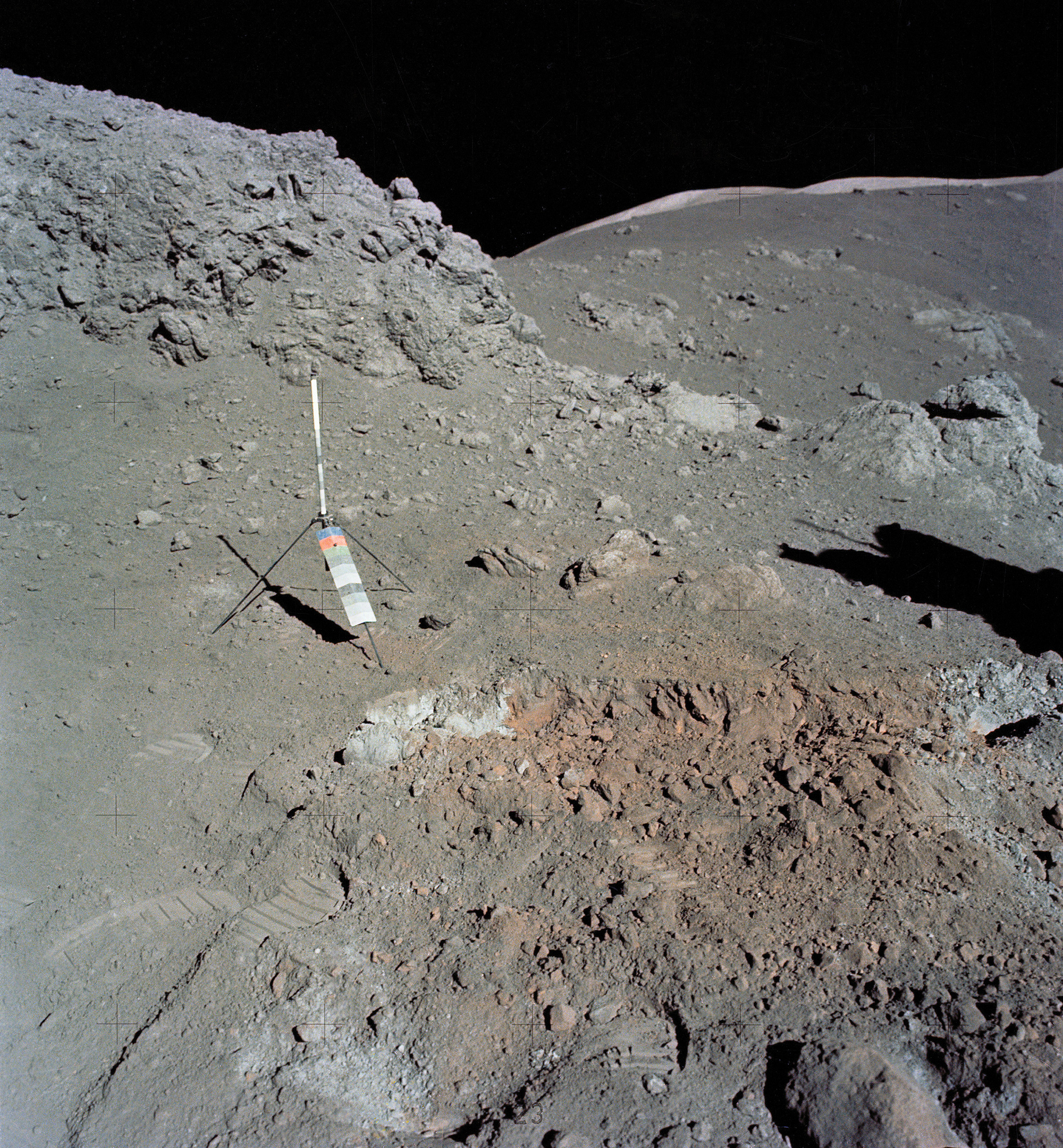

Schmitt only had three excursions over three days to explore the Moon, but the journey proved to be fruitful with the discovery of what appeared to be ‘orange soil.’

Schmitt: “The orange soil that I called it at the time, which became known once it got back here as orange volcanic glass, was something that a field geologist, you would like to think, would pick up. It was a pretty subtle coloration. And the debris layer that surrounded the crater Shorty was fairly subtle, but it is the kind of thing that a geologist’s eye is trained to pick up.

“It also related to one of the several working hypothesis that I had relative to the origin of that crater that we called Shorty. It looked very much like an impact crater. That was the most probable outcome of the studies. But we had entertained the possibility, based on the low resolution photographs we had, that it could be a volcanic crater.

“When we started to see coloration around it, that triggered in my mind the idea that we see color around the volcanos here on Earth due to alteration of the rocks and that hypothesis might still be valid. “It didn’t take very long looking at the crater Shorty however to be absolutely sure that it was indeed an impact crater so we had to come up with some other explanation for the presence of that orange volcanic glass in its rim.

“That is still an area of some debate right now. The most important aspect of the glass though is that it has opened up the real possibility that the water that has been discovered at the poles of the Moon may well be indigenous water, that is water that has come out of the Moon and migrated to the poles.

“Before the water was discovered in the orange volcanic glass – and that happened just a couple years ago – before that was discovered inside of the glass, the dominate hypothesis for the origin of water in permanently shadowed area of the poles, was that it has come from the impact of comets or water-bearing asteroids on the Moon. That is still a very real possibility and it may actually be a combination of several sources of water.

“But certainly the orange volcanic glass and its companion green glass that was found but not fully recognized on Apollo 15, those both have water in them. So, it has opened up the possibility that water has actually come from the interior of the Moon.”

Even after 40 years of study, the lunar rocks brought back from the Moon still are revealing their secrets to Schmitt and other researchers.

Schmitt: “The lunar samples are the gift that keeps on giving. There has been a very, very active lunar science community. They continue to come up with not only new ideas on what to test, but new technology on which to run those tests. Forty years ago you could not have detected the water in a small bead of volcanic glass. That was done just recently. Now we have the technology and equipment by which most kinds of analysis can be conducted.

“I continue to try to integrate the new information, both from the soils and from the robotic missions that have gone to the Moon. Most recently the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter has provided high resolution photography of most of the Moon, and in particular the Apollo landing sites. I’ve been going back into that photography to see if it enhances my understanding of what we saw when we were actually there.”

Heading out beyond the Moon is a goal that the geologist side of Schmitt definitely sees as the future of space exploration, but he is practical enough to realize that even with such an endeavor, the Moon will likely play an important role.

Schmitt: “I think the most obvious long-term goal, that is also the most technologically feasible in a long term goal, is Mars. But I think the fastest way to get there is to go back to the Moon, and use the Moon not only for a scientific understanding of the Earth and the Moon, but also to develop the techniques necessary for actually carrying out a Mars mission.

“The technology and operational procedures we will need on Mars and going to Mars will be very very different in what we are used to. The Moon however is a place only three days away and operations can be fully developed. Plus the Moon has resources that I think are going to be very important. Not only for providing the necessary consumables for going to Mars, and the protection from space radiation, and the water, but also enable to show us how to operate when you have no workable communications with the Earth.

“The astronauts that work on Mars, the geologists and others that work on Mars, are going to be totally on their own because the communication delay will make it impossible for what we call real-time communication with the Mission Control Center.

“That doesn’t mean the Earth won’t be involved, but it will be involved as an analytics, support and planning center rather than a place that actively provides real time support, such as we had on Apollo.

“I think most geologists would prefer working on Mars, rather than working on the Moon because there would be less interruptions.”

When it comes to STEM education, Schmitt believes that a certain way of teaching mathematics is the key to preparing the next generation of scientists and explorers.

Schmitt: “Mathematics, in particular, opens up a whole new spectrum of possible endeavors to any individual that studies it. Not only endeavors that link to every day life here on the planet, but other opportunities that will come in the future that are presently unforeseen.

“Mathematics is the language of those kind of opportunities, and students really need, more than anything else, is to be able to speak and think in that language much, much better than they normally do.

“I strongly recommend that people who are involved in the so-called STEM fields, that they consider that mathematics really needs to be taught as a language. So that it is readily available, and not something that you look up and have to read about.”

For the child of today looking to make the discoveries of tomorrow, both on Earth and in space, Schmitt thinks being prepared can only come with a broad education.

Schmitt: “With any field of endeavor, the teaching requirement is to be prepared. To be prepared not only for that field, but be prepared for that field to change. And the only way you can be prepared to do that is to have a really strong fundamental basic education. Not only in STEM fields. The science, technology, engineering and math – math again should be the first on that list – but also in other fields. Language, history, philosophy, all of those are important parts of your education. Those young people must concentrate on getting as broad and as basic an education as possible so that they will be flexible in the future.”

After leaving NASA, Schmitt successfully ran in New Mexico for a Senate seat in the U.S. Congress. He believes it is important that everyone stays informed about happenings in government.

Schmitt: “Everyone needs to be involved in politics, whether they want to be or not. The political field is what determines the way that our society is run, and the way it is governed, and how much liberty we are going to have.

“Most of the trends in recent times have been to restrict liberty rather than to enhance it. And so it is very, very important that people of all walks of life recognize that politics is something that they have to be involved in.

“They have to have as much information as they can gather in order to make the decisions, not only about elections, but about their role in society. That is being lost on an awful lot of people, including lost in our education system.

“But a system that allows the individuals, the voting public, the information they need to have in order to understand that being strong in space has many different benefits. Probably the most important is really related to our national security. That is, that the psychological benefit of the primary defender of liberty on this planet, being active and indeed dominate in space is extraordinarily important in the geopolitical sense.”

For Schmitt, the Moon has not been the final frontier, even though he continues to study it. There are still plenty of places to explore and discoveries to be made right here on Earth.

Schmitt: “Oh, no question about it, and that is why science is exciting to most of those people who are involved in it. In that you never know what is going to appear over the horizon, whether it is in the laboratory or in the field.

“The nice thing about geology is that almost any place you go still has places to explore and things to learn. And you never run out of opportunities, believe me.”

It’s been four decades since Schmitt last walked upon the Moon, and despite the fact that none have followed since, he does hold out hope for the future.

Schmitt: “It was very clear when I became the 12th person to step on the Moon, that there was not going to be any person to do that for some time. Now, did I think it would really be 50 or 60 years before that happened again? No.

“I am very disappointed that we still do not have a coherent plan to get back to the Moon and gather the scientific understanding that is waiting for us there, as well as the resources that are there.

“But again, I’m an optimist, I think if we get our education system put in great shape again, young people will lead us to the Moon, as they did in Apollo.

“That’s one of the things you have to remember is that Apollo was a young persons program. The vast majority of people in Apollo were in their 20s. And that is what makes these kinds of things happen. Young people with a good basic education, and also the motivation and stamina and imagination to really take on these kinds of projects. “I run into them every day.”

Apollo 17’s Gene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt recently spent more than a half hour apiece discussing a variety of topics with RocketSTEM. The phone interviews were conducted by Chase Clark, with assistance from Anthony Fitch. The conversations have been edited for length.