The rumble of a rocket engine and then a distant sonic boom break the breezy silence of a remote desert plain. Another unmanned commercial rocket has been launched from Spaceport America. Soon, perhaps in a few months, Virgin Galactic will begin space tourism flights with a futuristic spacecraft air launched from a mothership using Spaceport America’s 12,000-foot runway for takeoff and landing.

How did this, the world’s first purpose-built commercial spaceport, come to be built in southern New Mexico? It was the continuation of more than seven decades of space development in a geographic setting ideally suited for it.

A fruitful desert

It was Robert Goddard, inventor of the liquid fuel rocket, who first recognized New Mexico’s suitability for space research. After his dramatic fourth test launch in his home state of Massachusetts in 1929, the state fire marshal forbade any more launches. Goddard began searching for another location with the best possible features: a large expanse of flat open space, little vegetation to catch on fire, few people who could be frightened or injured during his tests, generally good weather throughout the year, power availability, and access to rail and air transportation. A higher elevation was also desirable for fuel conservation. He consulted with a meteorologist and with aviator Charles Lindbergh, who had flown over much of the country.

Finally, Goddard chose the town of Roswell in southeastern New Mexico. He and his assistants moved there in July 1930. His first rocket launch, in December 1930, reached an altitude of 2,000 feet and a speed of 500 miles an hour, far surpassing the 90 feet altitude and 60 mile-an-hour speed he had accomplished in Massachusetts. Working in New Mexico until 1942, he launched the first manmade vehicle to travel faster than the speed of sound and sent a rocket to an altitude of nearly 9,000 feet.

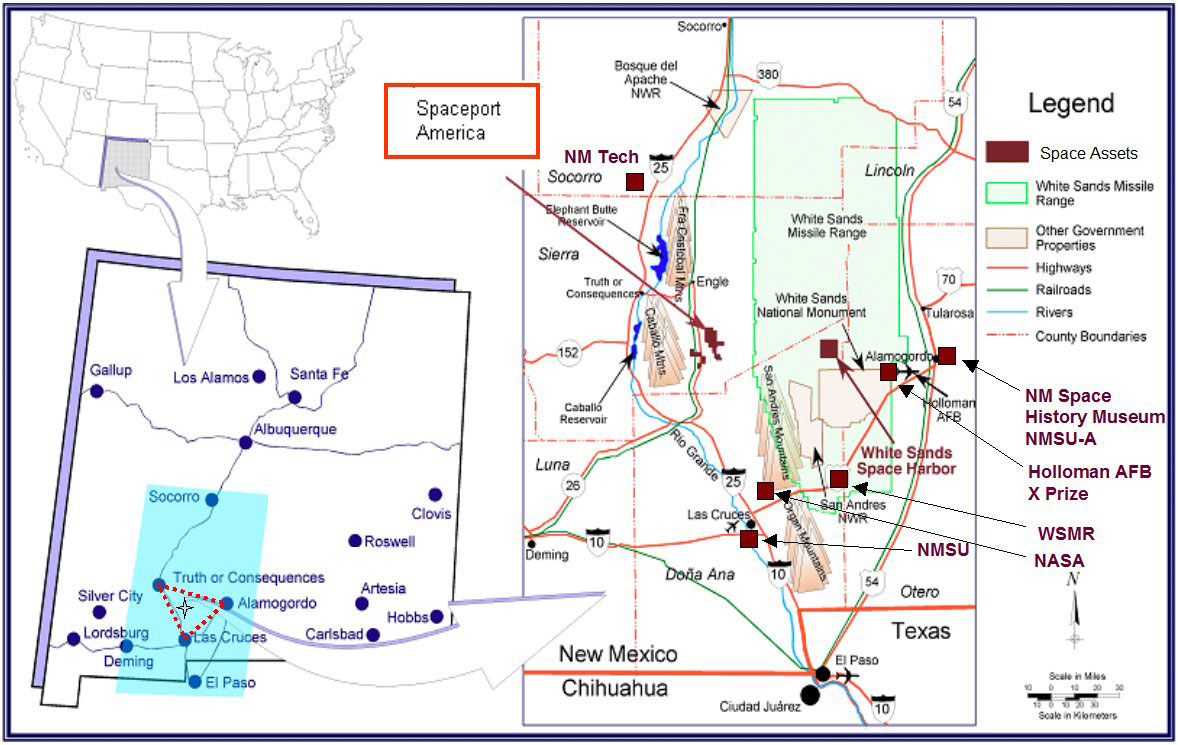

For essentially the same reasons Goddard had selected southern New Mexico for his test site, the US Army established White Sands Proving Ground a hundred miles west of Roswell in 1945. They launched their first atmosphere-testing rocket, the WAC Corporal, at White Sands three months later. Rocket development still continues at the White Sands facility, which was renamed White Sands Missile Range (WSMR) in 1958. Nearly all of the in-flight training for landing space shuttles was conducted at White Sands.

During the 1950s and early 1960s, researchers conducted vital experiments on human tolerance for space travel at Holloman Air Force Base, 50 miles east of White Sands Missile Range. Those experiments examined the effects of cosmic radiation, microgravity, acceleration and deceleration forces, and the physical and psychological effects of confinement in a small capsule in a near-space environment. The chimpanzees launched early in NASA’s Mercury program were trained at Holloman.

Ideas for commercializing space

By 1990, southern New Mexico had been involved with space programs for sixty years. It was part of the local culture in Las Cruces, a city twenty miles west of White Sands Missile Range. Burton Lee, whose mother lived in Las Cruces, was a consultant to NASA on the idea of developing an industry to supply commercial reentry capsules for research and commercial use. That program needed a recovery site for the capsules in the United States. Lee talked to a couple of leaders of the Physical Science Laboratory at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces and the director of the WSMR Flight Safety Office about possibly using the missile range for that purpose.

“At the same time, I was pursuing, on my own initiative, this idea of a spaceport,” Lee said on The Space Show in December 2006. “I wrote the initial market study, strategic plan, and business plan. I went to Washington to speak with [New Mexico] Senator [Pete] Domenici’s staff about what the spaceport could mean for the economic development of southern New Mexico.” In 1992, a group of aerospace executives joined him to form the Southwest Regional Spaceport Task Force to explore the viability of an inland commercial spaceport and its potential for economic development.

Meanwhile, in the early 1990s, the US government was pursuing the development of a reusable single-stage-to-orbit launch vehicle. The first prototype, the Delta Clipper Experimental (DC-X) developed by McDonnell Douglas, was flight tested at White Sands Missile Range between 1993 and 1996. After the DC-X test vehicle was disabled on its final test landing, NASA officials decided to pursue a different type of reusable single-stage-to-orbit launch vehicle, VentureStar, developed by Lockheed Martin. That company wanted to test its prototype at a commercial spaceport rather than a government facility. It requested bids for a launch site in 1998.

The New Mexico legislature had created an Office of Space Commercialization in its Department of Economic Development in 1994 to market and promote the state’s space-related resources and to coordinate, develop, and manage its regional spaceport program. Its staff wrote a proposal for hosting the VentureStar tests in southern New Mexico.

Fourteen states submitted bids for the VentureStar program, but the project was cancelled in 2001, just before site selection results were to be announced. In January 2002, a Lockheed Martin official told members of the New Mexico Space Commission, “You were number one. Your proposal was head and shoulders above the rest.” In response, the New Mexico Office for Space Commercialization’s executive director, Hanson Scott, said, “Even though there is no VentureStar program, New Mexico has proven that we have a strong team and other advantages from the point of view of being evaluated by a major aerospace company for a reusable space launch vehicle.”

During the 2002 election season, Bill Richardson was campaigning to be governor of New Mexico, and Rick Homans was his deputy campaign manager. “The first that we heard the word spaceport was campaigning in southern New Mexico,” Homans said. “We didn’t really understand it all too well, but we heard a lot of excitement, support, and enthusiasm about it.”

Richardson won the election and appointed Homans the state’s Secretary of Economic Development. A delegation from the Southwest Regional Spaceport Task Force visited Homans within weeks after he took office in January 2003. “They laid out this concept of an inland spaceport that would be very useful and workable with the development of reusable launch vehicles and reusable booster systems,” Homans said. “They said, in a very visionary kind of way, ‘We’re not asking you to do anything except to listen and to understand and to wait for the right time. The biggest mistake would be to move forward prematurely. We have to wait for this industry to begin to emerge, and that’s when we go forward.’”

Commercial space events

They didn’t have to wait long. In a few months, a package arrived on Homans’ desk. In it was an invitation to bid on being the host site for an annual competition for commercial space vehicles. Competition was already underway for the Ansari X Prize, a $10 million award for development, without government funding, of a three-person reusable suborbital spacecraft. Twenty-six teams were competing for that prize, and at most one would win by the contest deadline of December 31, 2004. Peter Diamandis, organizer of the Ansari X Prize, wanted to encourage contenders to continue developing their concepts after that deadline, so he created the X Prize Cup. It would be an annual event held in the same place every year for commercial space industry competitions and for stimulating public interest.

“As I opened this envelope and laid it out, there were 8-by-10 color glossies of different kinds of technologies from all over the world for reusable launch vehicles [for the Ansari X Prize competition],” Homans said. “And as I had it out there and saw this description of the X Prize Cup, it just hit me that this is what the beginning of a new industry looks like. We realized if we are going to claim the right to help give birth to this new industry, we have to win the right to hold the X Prize Cup.”

New Mexico’s was one of four proposals submitted for hosting the X Prize Cup. In May 2004, New Mexico was selected over Florida, California, and Oklahoma. “It took many years of environmental studies and technical feasibility safety studies to prove that inland launch would be safe,” Lee said. “Those original studies were done for the single-stage-to-orbit [VentureStar] program and laid the technical basis … to propose to the X Prize Foundation to host the X Prize Cup and to base Spaceport America out of the Las Cruces area.”

Defining the first competition, raising prize money, and allowing development time for competitors would take time, but Diamandis wanted to start encouraging public interest more quickly. A preliminary event, the Countdown to the X Prize Cup, featured exhibits and demonstrations of existing technologies in October 2005 in Las Cruces. Between 10,000 and 15,000 people attended several events over a four-day period.

NASA signed on as the sponsor of the first X Prize Cup competition. It offered $2 million for two levels of awards in two categories for preliminary development of an unmanned lunar lander. In general terms, the rocket-powered vehicle had to rise to a specified height above a launch pad, travel a specified distance horizontally, and land on another pad after a minimum flight time. The vehicle could then be refueled before repeating the flight and landing back on the original launch pad. Each team had two and a half hours to move their vehicle from a staging area to the launch pad, complete both legs of the flight, and return the vehicle to the staging area.

Four teams signed up, but only one was ready to compete in the first X Prize Cup in October 2006 at the Las Cruces airport. No prizes were awarded, but 15,000 to 20,000 people watched the lunar lander challenge and other events.

The 2007 X Prize Cup was held at Holloman Air Force Base. Again, only one of the teams was ready for competition, and no prize was awarded. The two-day event attracted at least 80,000 people.

Because of funding and scheduling issues, the X Prize Cup event was not held in 2008. However, the lunar lander challenge competition was held at the Las Cruces airport that October. Armadillo Aerospace won the first of the prizes with a successful pair of flights by its Mod vehicle. In 2009, teams were allowed to attempt the lunar lander competition at individual sites of their choosing. Armadillo Aerospace and Masten Space Systems won the remaining three prizes in Texas and California, respectively.

Creating the spaceport

The X Prize Cup might be considered the tipping point for getting New Mexico’s spaceport from a vision to a reality. In June 2004, a month after his state was selected for the competition site, Homans went to California to observe the first full test flight of SpaceShipOne, a leading contender for the Ansari X Prize. On that flight, the commercial spacecraft was air-launched from a mothership and flew just above the 62 miles required to win the prize. Two months later, it would fly even higher and repeat the feat in less than two weeks to win the prize. The test flight impressed Homans on both emotional and practical levels. “It did not escape us, the huge significance of this being the beginning of a whole new industry in which New Mexico will play a very big role,” he said.

The significance of SpaceShipOne also did not escape Richard Branson, founder of the Virgin family of companies. He established Virgin Galactic, which he envisioned as the world’s first commercial spaceline, offering passenger spaceflights as an airline offers commercial airplane flights. He contracted with Burt Rutan, the designer of SpaceShipOne, to expand the concept into a mothership and spaceship (SpaceShipTwo) that could carry a pilot, a copilot, and six space tourists. Homans saw it as another opportunity for New Mexico’s space industry. “Just like with the X Prize Cup, we said that it was absolutely essential that we recruit Branson to operate out of New Mexico,” he said.

In 2005 New Mexico established the state’s Spaceport Authority, with Homans as its first chairman. He and Richard Kestner, the director of the Office of Space Commercialization, flew to London to pitch a new spaceport to Virgin Galactic officials. They were armed with several space tourism polls and economic impact studies. In December 2005, Branson announced that the world headquarters of Virgin Galactic would be established in New Mexico. The following month, he came to Santa Fe to lobby New Mexico legislators. The lawmakers appropriated $110 million toward building the Southwest Regional Spaceport, which was soon renamed Spaceport America. Two counties directly affected by the spaceport’s location passed tax increases to provide the rest of the $210 million needed to design and build the facility.

The location chosen for the spaceport is a 28-square-mile parcel 45 miles north of Las Cruces. It is adjacent to the western boundary of White Sands Missile Range, which has restricted air space to unlimited altitudes and offers support with flight tracking and payload recovery.

Spaceport activity

Virgin Galactic signed on as the anchor tenant for Spaceport America, but it would not be the only tenant. In 2006, UP Aerospace began launching unmanned suborbital rockets carrying government research payloads, student experiments, and commercial cargo. At that time, the spaceport’s only facilities were a launch pad and three small buildings. By January 2014, UP Aerospace and Armadillo Aerospace had conducted twenty unmanned vertical launches from the spaceport. A larger launch facility is being constructed for use by SpaceX, which signed a three-year agreement to test its Falcon 9R rocket there.

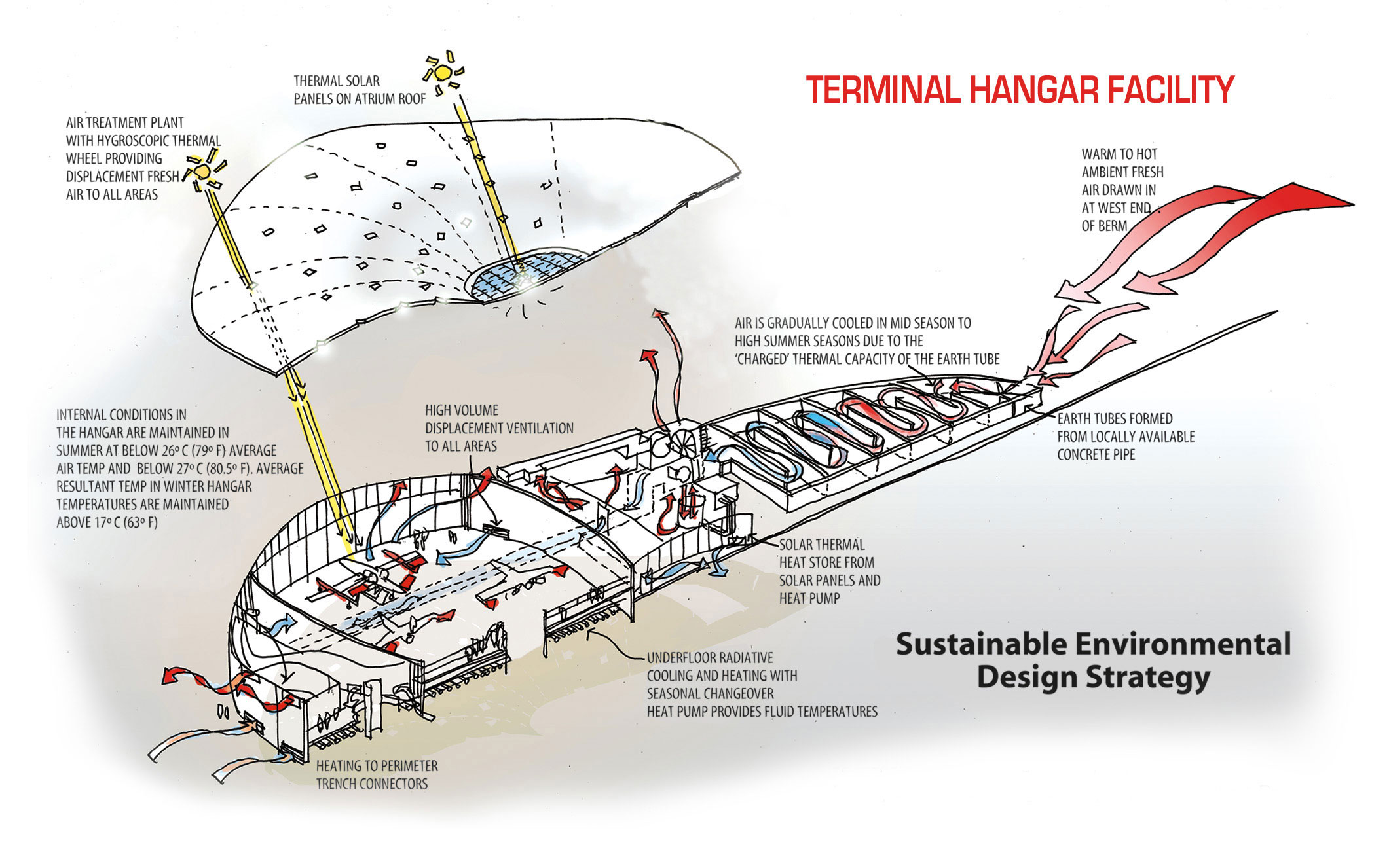

The most visually appealing part of Spaceport America, the Gateway to Space, received a certificate of occupancy in late 2012 and the interior is currently being fitted out by Virgin Galactic. A combination terminal and hangar, the building will house up to two motherships and five spaceships. It will also have lounge and observation spaces for ticket holders and their guests. As of this writing, Richard Branson plans/hopes to be on the first passenger-carrying flight from Spaceport America during the spring of 2015.