Perihelion: 2020 May 4.95, q = 1.615 AU

After devoting my “Comet of the Week” last week to the first comet I ever observed, it seems appropriate to devote this week’s “Comet of the Week” to the brightest comet that is currently visible in our nighttime skies, and which is easily accessible for observations, at least from the northern hemisphere. The full moon early this week might affect observations initially, but by the latter part of the week, and later, the comet should be easy to see.

The comet in question is a discovery of the Panoramic Survey Telescope And Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS) program based at Mount Haleakala in Hawaii, the most prolific of the current near-Earth asteroid survey programs. Pan-STARRS originally comprised a 1.8-meter telescope that first went on-line in 2010, and has recently been joined by a second telescope of the same size. Pan-STARRS made its first comet discovery in October 2010 and has since gone on to find many, many more; at this writing its count of comet discoveries stands at 203, although this will clearly continue to increase. Most of the Pan-STARRS comet discoveries are very faint objects – 20th magnitude or fainter — and stay that way, but a relative few do become somewhat bright, usually many months, or even a year or two, after their discovery. The brightest Pan-STARRS comet thus far is C/2011 L4, which became as bright as magnitude 1.5 when it passed through perihelion in March 2013, although its elongation from the sun was quite small at the time and it was not an especially easy object to see.

Pan-STARRS discovered this comet as far back as October 2, 2017, over 2 ½ years before its perihelion passage, and in fact pre-discovery images back to September 15 were later identified. At the time of its discovery, the comet was located at a heliocentric distance of 9.25 AU and was a rather faint object near 19th magnitude. It has brightened steadily since then, and after being in conjunction with the sun in May 2018 was widely imaged during the last few months of that year and first few months of 2019, being at opposition in mid-November 2018 and brightening from about 16th magnitude to 15th during that period.

After being in conjunction with the sun again in mid-May 2019 Comet PANSTARRS began emerging into the morning sky during July when it was near 14th magnitude, and shortly thereafter it began to be picked up visually. It has brightened steadily since then, being at opposition in early December and being closest to Earth (1.52 AU) on December 29. Although now receding from Earth it is still approaching perihelion in early May, and thus it remains moderately bright near 10th magnitude; it should at least maintain this brightness, and perhaps might even brighten slightly, over the next few weeks.

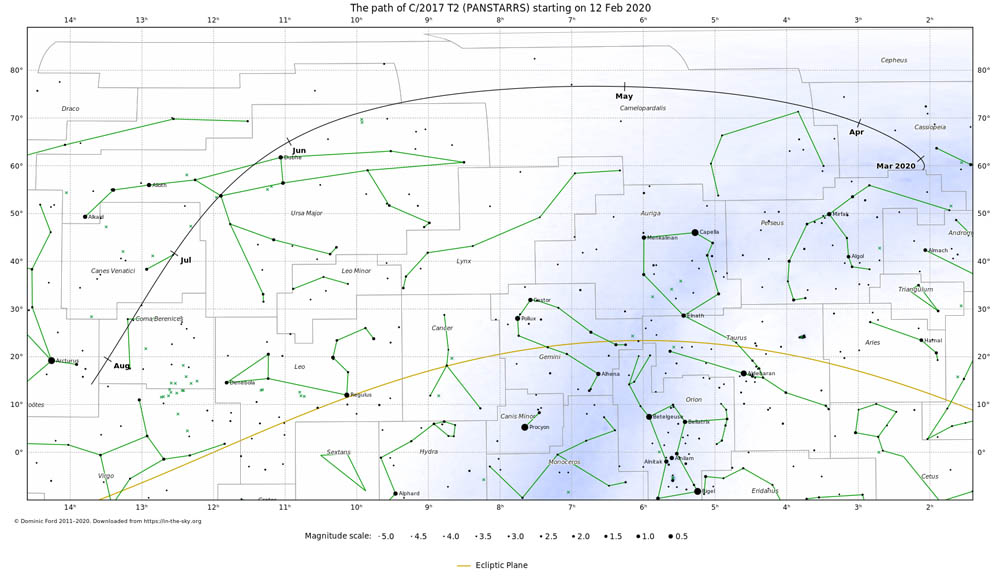

During this week the comet is located in eastern Cassiopeia just a few degrees northwest of the “Double Cluster” in Perseus. Over the next few weeks, it travels to the north-northeast and then curves more directly northeastward; it passes just three degrees east of the star Epsilon Cassiopeiae (the easternmost star of the “W”) in mid-March and then traverses the obscure constellation of Camelopardalis and comes to within 14 degrees of the North Celestial Pole around the time it is at perihelion in early May. It then starts heading southeastward as it crosses into Ursa Major, and passes one degree northeast of the bright galaxies M81 and M82 around May 23 and then crosses diagonally – northwest to southeast – across the “bowl” of the Big Dipper during the first half of June. Afterwards it travels through the constellations of Canes Venatici and Coma Berenices – passing through the eastern regions of the distant Coma Cluster of Galaxies in mid-July – and then through Bootes and (by late August) into Virgo. By that time it will be getting low in the western sky after dusk and will presumably have noticeably faded.

Comet PANSTARRS appears to be rather bright intrinsically, and it is unfortunate that it does not come close to either the sun or Earth. It also appears to be a first-time visitor from the Oort Cloud, and as was discussed in an earlier “Special Topics” presentation, such objects tend to under-perform when compared to initial expectations. However, the only way to determine how bright Comet PANSTARRS might become is to observe and study it as it makes its passage through the inner solar system. The Comet Resource Center at the Earthrise web site will contain regular updates as to its actual performance.

Although there aren’t any especially bright comets currently known that will be coming to perihelion within the near future, there are a few somewhat bright ones that will be appearing within the next few months. Comet 2P/Encke, which has the shortest orbital period of all known comets, passes through perihelion in late June and will be visible from the southern hemisphere afterwards, and will be featured as a “Comet of the Week” around that time. Two long-period comets, both discovered by the ATLAS program based in Hawaii this past December, could become interesting within the near future: Comet C/2019 Y1 is currently around 12th magnitude but could become somewhat brighter around the time it passes through perihelion in mid-March, and Comet C/2019 Y4, while currently a relatively faint object of 16th magnitude, passes through perihelion at the end of May at the small heliocentric distance of 0.25 AU and, at least theoretically, could become fairly bright. Both of these comets appear to be members of comet “groups,” suggesting that they might be fragments of comets that have split; this is the subject of a future “Special Topics” presentation. As with Comet PANSTARRS, the Comet Resource Center will carry information about these and other various comets as they make their respective appearances.

Meanwhile, another intrinsically bright Comet PANSTARRS discovered in 2017, C/2017 K2, is also on its way in, and does not pass perihelion until late 2022. It has the potential to become a rather bright object, although it will not be especially well placed for observation around the time it is brightest, and – unfortunately for those of us in the northern hemisphere – will only be accessible from the southern hemisphere at that time. It will be a future “Comet of the Week.”

More from Week 7:

This Week in History Special Topic Free PDF Download Glossary

Ice and Stone 2020 Home Page