Perihelion: 1943 February 6.72, q = 1.354 AU

The name of Fred Whipple is legendary in cometary astronomy. He spent several decades as an astronomer and professor at Harvard University, and is best known for developing what he called the “icy conglomerate” model of a comet’s nucleus (more commonly referred to as the “dirty snowball”) in a series of papers in the mid-1950s; spacecraft missions decades later verified the essential correctness of his model. Among other accomplishments, he also invented the “Whipple Shield” that protects spacecraft – including crewed platforms like the International Space Station – from micrometeoroid impacts.

During his early years at Harvard Whipple was involved in photographic patrol work, primarily of meteors. While engaged in this effort, between the early 1930s and early 1940s he discovered one asteroid – (1252) Celestia, which he named after his mother – and six comets. One of these is the short-period object now known as 36P/Whipple which, primarily as a result of a close approach to Jupiter in 1981, now travels in an orbit with a period of 8.4 years and the rather large perihelion distance of 3.0 AU which causes it to remain faint. It will pass through perihelion at the end of May.

Whipple discovered his last, and best, comet on a patrol photograph that had been taken on December 8, 1942, and later he was able to identify it on earlier photographs extending as far back as November 5. The various nations of the world were at the time embroiled in World War II, and thus communications between nations could be quite difficult; while the comet was initially referred to in the U.S. as “Comet Whipple,” word of independent discoveries elsewhere eventually came to light, including ones by Carl Fedtke at Konigsberg Observatory in East Prussia (now Kaliningrad in Russia) on December 11 and by G.A. Tevzadze at the Abastumani Observatory in the Caucasus Mountains (in what is now Georgia) on December 15. Even the preliminary discovery designation caused difficulties: the comet was called “1942f” in the U.S. but “1942g” in Europe, and several months elapsed before this could be straightened out. (For what it’s worth, the comet’s old-style perihelion designation is 1943 I and its new style designation is C/1942 X1.)

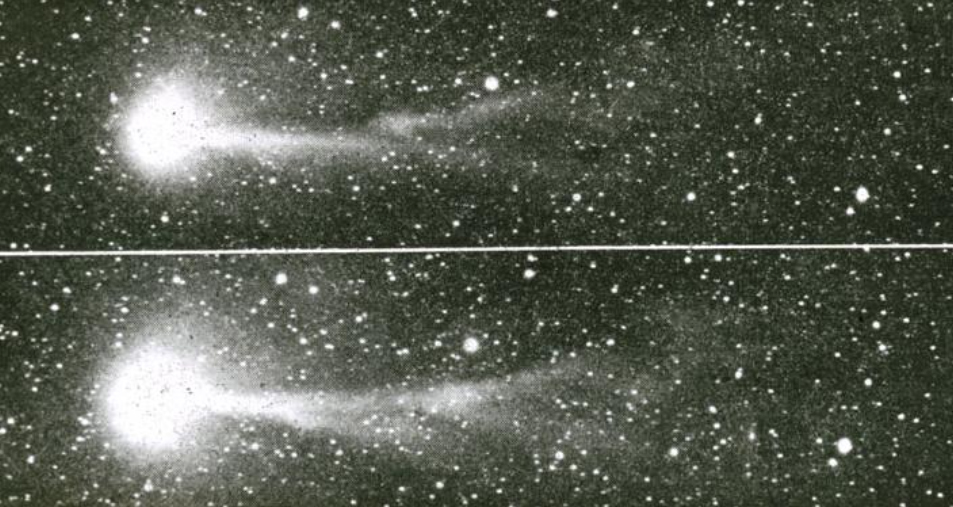

The comet remained well placed for observation, especially for observers in the northern hemisphere, for the next several months, and was nearest Earth (0.43 AU) in late January. Initially around 9th or 10th magnitude around the time of its discovery, it brightened unexpectedly rapidly, already being brighter than 6th magnitude by mid-January and being close to 4th magnitude by the end of that month. It then began fading, as expected, and had dropped to 5th magnitude by the second week of February, however it then underwent an unexpected surge in brightness, being near magnitude 3 ½ during the latter days of February. It was crossing the “bowl” of the Big Dipper at that time and thus was amenable to casual observations; for example, the May 1943 issue of “Sky & Telescope” contains a dramatic first-hand account of an “independent” discovery by a U.S. Navy Quartermaster, Francis Wilmot, from aboard ship in the Atlantic Ocean.

Afterwards, the comet began fading again, dropping below naked-eye visibility in early April, although it exhibited occasional small and short-lived brightness increases during that period. It faded more “normally” after that, with the last observations being obtained in early August.

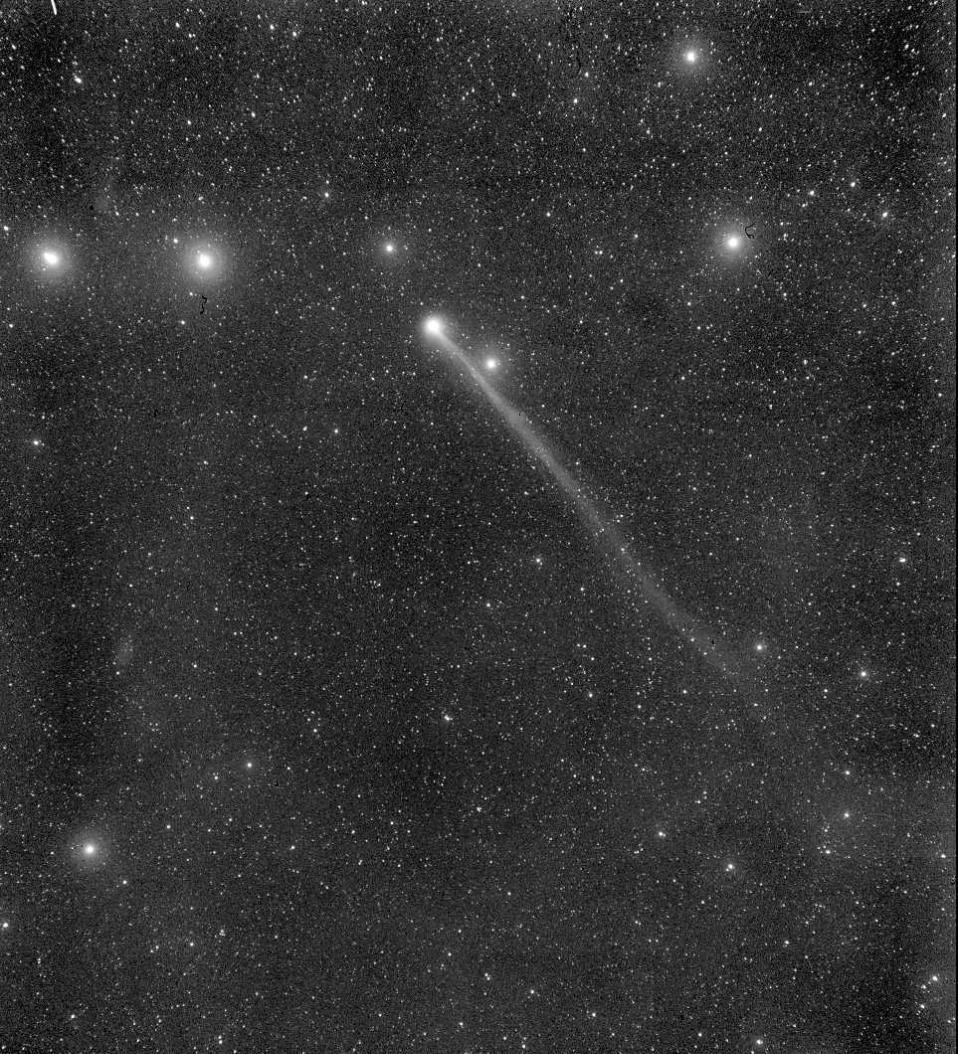

Comet Whipple-Fedtke-Tevzadze was a very dust-poor comet and thus didn’t exhibit much of a dust tail, but it did exhibit a rather long and distinct ion tail, which reached a maximum visual length of about six degrees but extended up to almost 20 degrees on photographs. This tail also exhibited various signs of structure and activity, including at least one disconnection event in late March. At the same time, photographs appeared to indicate a small secondary nucleus, with the best calculations indicating a splitting date around March 9 – curiously, a few weeks after the major brightness increase that often accompanies fragmentation of a comet’s nucleus. In any event, the near-nucleus activity and the goings-on within the ion tail appear to be unrelated to each other, which serves to highlight the wide range of independent physical and chemical processes that take place within comets as they make their passages around the sun.

More from Week 9:

This Week in History Special Topic Bonus Content Free PDF Download Glossary

Ice and Stone 2020 Home Page