Perihelion: 1996 May 1.40, q = 0.230 AU

Following the discovery of Comet Hale-Bopp in mid-1995, the entire world was awaiting its expected good show in 1997. But while we were waiting, another comet came by and provided another stunning show. This object was discovered on January 30, 1996 by a Japanese amateur astronomer, Yuji Hyakutake, who curiously had discovered another comet (C/1995 Y1) just five weeks earlier only three degrees away from this one’s discovery location.

At the time of its discovery this newer Comet Hyakutake was about 10th magnitude and moving very slowly from night to night. Once its orbit was determined the reason for the comet’s slow apparent motion became obvious: it was headed almost directly towards Earth. It would pass only 0.102 AU from Earth on March 25 – the seventh-closest approach of any known comet to Earth in the 20th Century, and, intrinsically, the brightest comet to pass this close to Earth since the mid-16th Century.

Comet Hyakutake brightened rapidly during the ensuing weeks, and reached naked-eye visibility by the beginning of March. By mid-March it had brightened to 3rd magnitude and was exhibiting a coma almost one degree in diameter, with an ion tail up to five degrees long or longer. On the night of its closest approach, when it was located near the Big Dipper, it was as bright as magnitude 0, with a coma 1 ½ degrees in diameter, and according to my measurements exhibited an ion tail over 50 degrees long; telescopically the inner coma was quite active with distinct jetting activity. Two nights later, when the comet passed near the North Celestial Pole, the brightness had dropped slightly to 1st magnitude, however our view of the tail had become more broadside, and I measured a length of 70 degrees – the longest cometary tail I have ever seen – and some observers reported it as being as long as 100 degrees.

The comet continued fading somewhat as it receded from Earth, and the apparent tail length also decreased somewhat, although by this time a dust tail was also beginning to appear; I was still measuring lengths as long as 45 degrees by mid-April. By this time its elongation was starting to get low as the comet made its approach to perihelion, and when it disappeared into evening twilight during the last week of April it was between 2nd and 3rd magnitude.

There was hope that the comet might brighten again as it passed through perihelion, but this did not happen. It did, however, put on a good showing in the LASCO coronagraphs aboard the joint NASA/ESA SOlar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft that had been launched in late 1995, where it exhibited not only regular ion and dust tails but also a straight third tail that analysis indicated was made up of massive particles that had been ejected from the nucleus during the preceding few days. Following perihelion it was picked up from the southern hemisphere during the second week of May as a 3rd-magnitude object deep in morning twilight with a bright 3-degree-long dust tail. It faded as it receded from the sun and traveled southward, dropping below naked-eye visibility in early June, with the final visual observations being obtained during the latter part of August and the final images being recorded in early November.

As might be expected, Comet Hyakutake was intensely studied from a scientific standpoint, and was observed with a number of instruments, including the Hubble Space Telescope which detected the presence of several small “condensations” in the inner coma that were apparently very small fragments (no more than 15 meters across) that had recently broken off the nucleus. Meanwhile, radar bounce measurements obtained with NASA’s Deep Space Network antenna in Goldstone, California indicated that the nucleus was quite a bit smaller than expected, no more than 2 to 3 km in diameter. The fact that, intrinsically, the comet was as bright as it was – comparable to the intrinsic brightness of Comet 1P/Halley – indicates that a much larger percentage of the nucleus’ surface area was active than was Halley’s.

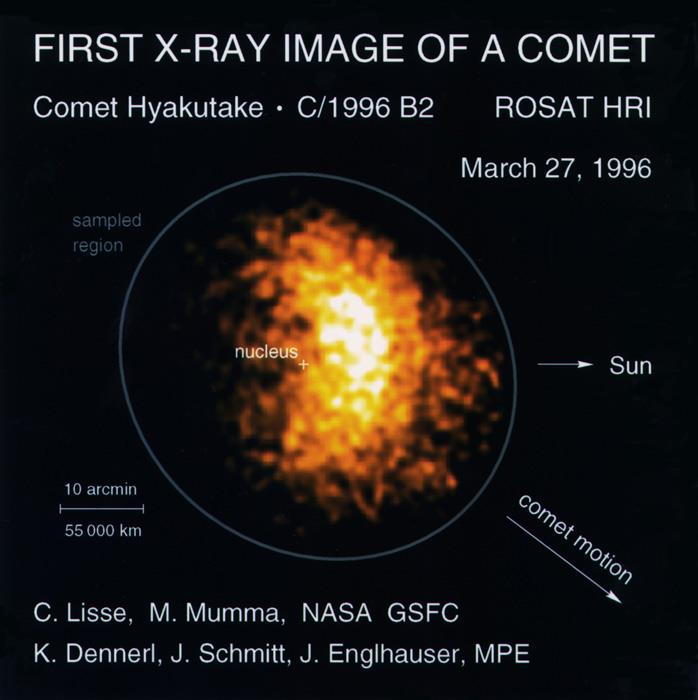

One of the most remarkable scientific observations of Comet Hyakutake was the detection of x-rays by the German Roentgensatellit (ROSAT) x-ray astronomy satellite, initially on March 27 and then on several subsequent occasions. The x-rays came from a crescent-shaped region some 30,000 km sunward of the comet’s nucleus, and once the scientific team knew what to look for, they were able to identify x-ray detections from several previous comets in archived ROSAT data including, remarkably, from the otherwise obscure Comet Arai 1991b some six weeks before that object’s discovery. The origin of cometary x-rays remained a mystery for some time, but was finally explained by observations of Comet LINEAR C/1999 S4 by the Chandra X-ray Observatory in July 2000, which showed that they are produced by charge-exchange reactions between very energetic particles in the solar wind and neutral atoms and molecules in the comet’s environment.

One other noteworthy scientific result came from analysis of magnetic field data taken by the joint NASA/ESA Ulysses spacecraft in May 1996, at which time Ulysses was located at a heliocentric distance of 3.7 AU. The data indicates that Comet Hyakutake’s ion tail was at least 3.8 AU long – by far, the longest cometary tail ever detected – and moreover exhibited distinct curvature, which is contrary to previously held assumptions. This appears to vindicate some of the extremely long tail measurements that some observers made in late March, which were longer than was geometrically possible – under the assumption that the ion tail points directly away from the sun in a straight line.

Comet Hyakutake was the first “Great Comet” to appear after the development of much of modern computer and communications technology, including the Internet. It thus enjoyed a strong virtual presence, including a NASA-sponsored “Night of the Comet” World Wide Web “party” at the time of its closest approach to Earth. Together with the impacts of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 into Jupiter two years earlier and the display of Comet Hale-Bopp the following year – both of these objects being future “Comets of the Week” – Comet Hyakutake helped spawn a dramatic renewal of popular interest in comets during the mid- to late 1990s. Such are among the legacies of what was truly a most remarkable comet.

More from Week 13:

This Week in History Special Topic Free PDF Download Glossary

Ice and Stone 2020 Home Page