Perihelion: 1957 April 8.03, q= 0.316 AU

There weren’t any bright comets that appeared the year I was born, 1958, but two bright comets appeared the previous year. These two objects were the brightest comets to become easily visible from the northern hemisphere since the return of Comet 1P/Halley in 1910.

The first of the two comets was discovered by Sylvain Arend and Georges Roland on routine asteroid patrol photographs taken at Uccle Observatory in Belgium on November 8, 1956, although the comet’s images weren’t noticed until a week and a half later. Being around 11th magnitude at the time and close to opposition, it was found to be five months away from perihelion passage, and it brightened steadily over the coming months as it approached the inner solar system. During January 1957 it was between 9th and 10th magnitude, and it brightened further to about 7th magnitude by the time it disappeared into evening twilight around the end of February.

After being hidden in sunlight for about a month, Comet Arend-Roland became briefly visible from the southern hemisphere around the beginning of April. The comet’s elongation remained small – never exceeding 18 degrees – but according to reports, including those made by scientists in Antarctica for the International Geophysical Year (which officially began on July 1), it was as bright as 2nd magnitude with a tail up to 5 degrees long. Before long it disappeared back into sunlight en route to a second conjunction with the sun.

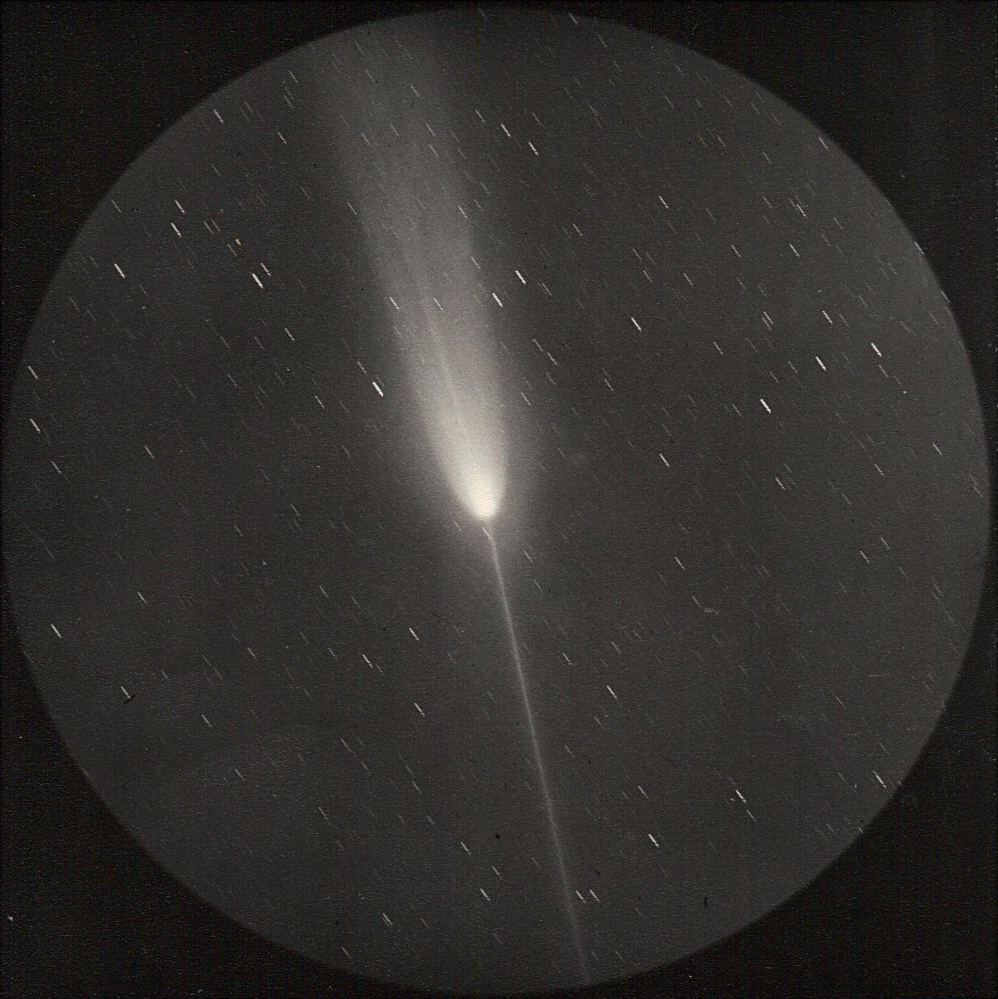

Around April 20 Comet Arend-Roland emerged back into the northern hemisphere’s evening sky, rapidly traveling northward; closest approach to Earth (0.57 AU) was in fact on the 20th. Initially it was as bright as magnitude 1 or 0, with a bright dust tail – likely enhanced due to forward scattering of sunlight – 25 to 30 degrees long. It faded fairly rapidly, being close to 3rd magnitude, although still with a 15-degree-long tail, by the end of April.

A particularly striking feature of Comet Arend-Roland during the latter days of April was the presence of a prominent sunward-pointing tail, or “anti-tail.” Initially this appeared as a somewhat broad fan, which became narrower each day until April 25 when it appeared as a very narrow “spike” extending up to 15 degrees from the coma. During subsequent days this expanded into a fan shape again, although on the opposite side of the coma from where it had been previously, and it also faded dramatically, disappearing by the first few days of May.

This “anti-tail” was due to dust grains that had been ejected from the comet before perihelion, which in turn lagged behind the comet as it made its passage through perihelion and began its trek away from the sun. This material remained in the plane of the comet’s orbit, which Earth crossed on April 25; on that day, we were seeing this material exactly edge-on, and slightly askew on the days immediately before and after. The “anti-tail,” then, was merely a projection effect, caused by sunlight being scattered off these dust grains in the comet’s orbit. Various other comets have also exhibited “anti-tails,” although that of Arend-Roland probably remains the most dramatic example.

By May the comet was entering northern circumpolar skies, and it faded below naked-eye visibility around the middle of that month. Visual observations continued until the latter part of June, and photographically it was followed until April 1958, by which time it had become very faint; two months earlier it had passed within a few arcminutes of the North Celestial Pole.

With the five months of lead time before perihelion passage Comet Arend-Roland was a well-studied comet from a scientific perspective including, as previously mentioned, by scientists involved with the International Geophysical Year. It was the first comet to be detected with radio telescopes, but such was the state of the technology at the time that little useful science could be obtained from these observations, other than rough examinations of the evolution of large-scale phenomena in the comet’s coma and tail.

Comet Arend-Roland turned out to be a first-time visitor from the Oort Cloud, and the gravitational perturbations it encountered during its passage through the inner solar system were enough to place it into a slightly hyperbolic orbit and thus eject it from the solar system altogether. It will thus never be seen again . . . However, just a few months later another bright comet, Comet Mrkos 1957d, graced the nighttime skies of Earth, and this object will be a future “Comet of the Week.”

More from Week 17:

This Week in History Special Topic Free PDF Download Glossary

Ice and Stone 2020 Home Page