Perihelion: 2020 May 31.04, q= 0.251 AU

Last year, when I selected the various comets I would be using for “Ice and Stone 2020”’s “Comets of the Week,” I did so with the knowledge – and even hope – that I might find it necessary to swap one or more such selections for current comets that showed potential for becoming bright. I am doing so this week, although unfortunately it does not appear that the comet in question is going to be as bright or spectacular as we might have hoped. Still, it is turning out to be a very interesting object that is attracting a lot of attention right now.

The comet was discovered on December 28, 2019 by the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) survey based in Hawaii; at that time it was a dim object of 19th magnitude. While its small perihelion distance attracted attention almost right away, what really caught astronomers’ attention was the fact that its orbit bears a striking resemblance to the Great Comet of 1844 (old style designation 1844 III, new style C/1844 Y1). Both comets have orbital periods in the neighborhood of 4000 to 4500 years, and it is thus very likely that they are two components of a single comet that split up in the past, perhaps around the time of its previous perihelion passage.

The Great Comet of 1844 passed through perihelion in mid-December of that year and was first observed from the southern hemisphere a few days later. It remained exclusively visible from the southern hemisphere, and was at its best during late December and in early January 1845, when according to the accounts of the time it perhaps reached a peak brightness of magnitude 0 and exhibited a bright tail up to 10 degrees long. Unfortunately, there do not seem to be any surviving paintings or sketches of it from that time.

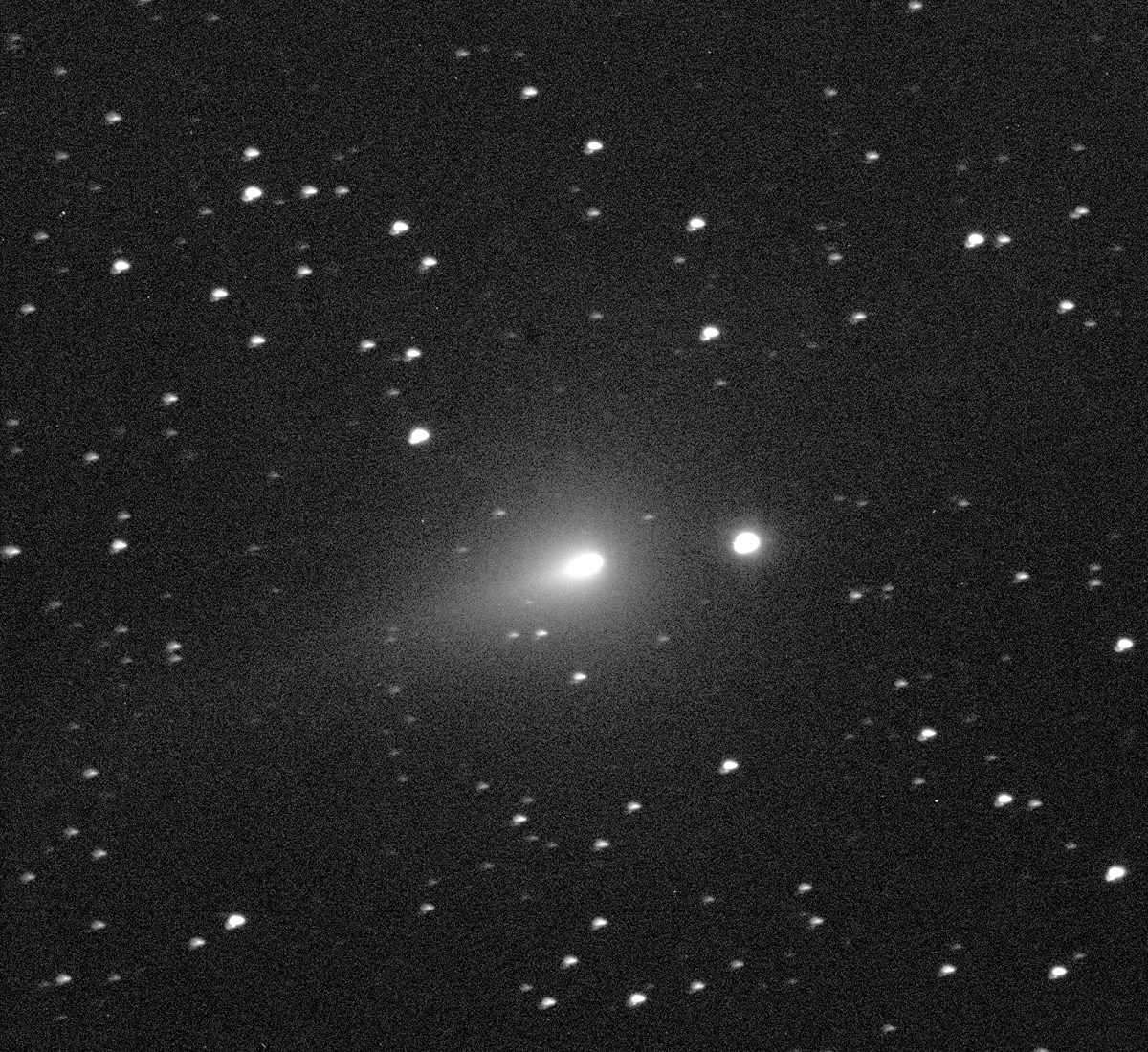

In general, trailing components of split comets tend to be smaller, and thus fainter, than the leading components, and indeed Comet ATLAS initially appeared to be much fainter, intrinsically, than its predecessor. However, it underwent a dramatic rapid brightening as it approached perihelion, and I personally observed an increase in brightness of four magnitudes (from 13th magnitude to 9th magnitude) between late February 2020 and mid-March. By the latter part of March it was approaching 8th magnitude and was exhibiting a large gaseous coma up to 12 arcminutes or more in diameter. While there was no reason to expect it would maintain that rate of brightening up until perihelion passage, at the time it seemed rather likely that it would at least become moderately conspicuous to the unaided eye.

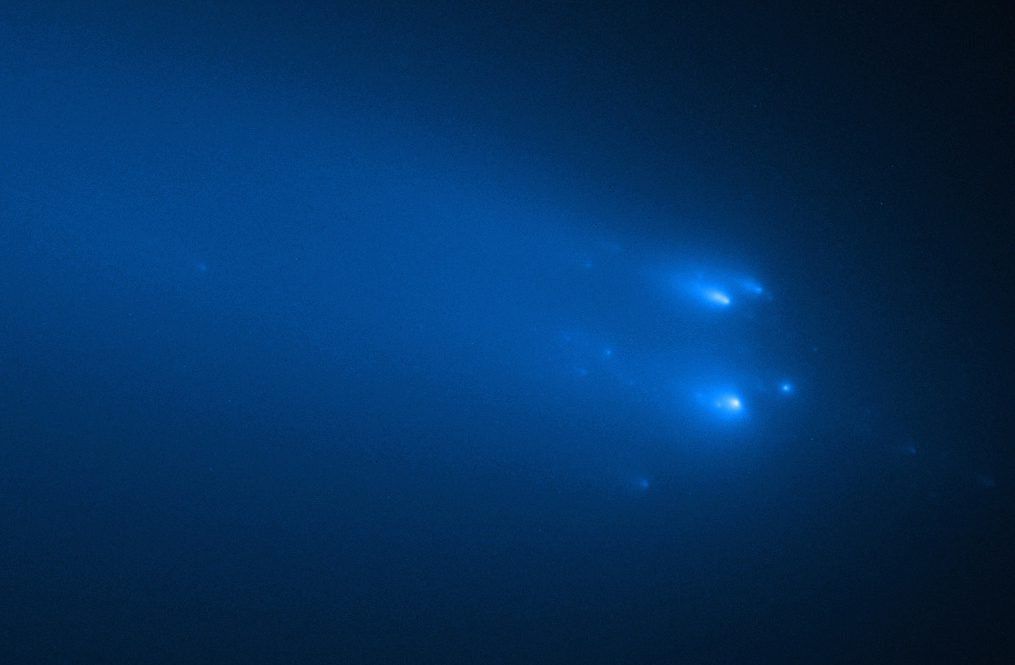

However, in early April various observers began to report that the comet’s nucleus appeared to be breaking up. Within a couple of weeks several distinct nuclei were apparent in the inner coma, and the comet itself had faded by over a magnitude; visually, instead of a relatively bright central condensation like it had exhibited earlier, the central region appeared as a dim, elongated “streak” – a sure sign of disintegration.

High-resolution images of Comet ATLAS’ nuclear region currently show several distinct fragments, and as time goes by it appears that some of these are continuing to fragment “cascade”-style. A very preliminary analysis by comet scientist Zdenek Sekanina suggests that the first splitting event occurred around or just before mid-March – right around the time that the rapid brightness increase began slowing down – although a more recent analysis (incorporating observations made with the Hubble Space Telescope) raises the possibility that the fragmenting process may have actually started many years ago.

At this writing Comet ATLAS is about 10th magnitude and is located in the northern hemisphere’s northwestern sky during the evening hours. Whatever might be left of the comet drops rapidly towards the northwestern horizon over the next couple of weeks, and after being in conjunction with the sun (24 degrees north of it) on May 20 it is better visible in the morning sky, although it will be close to the horizon in twilight and at best will be difficult to observe. If the comet survives perihelion passage it will be in the southern hemisphere’s morning sky beginning in early June, although during the subsequent weeks it remains at a fairly small elongation from the sun as it recedes from the sun and Earth.

It currently thus appears rather likely that we will not be getting any kind of bright and conspicuous showing from Comet ATLAS. However, perhaps in compensation there have been two comets discovered within the recent past that both show some potential of becoming somewhat bright within the near future. The first of these is Comet SWAN C/2020 F8, which was discovered by Australian amateur astronomer Michael Mattiazzo in images taken with the Solar Wind ANisotropies (SWAN) ultraviolet telescope aboard SOHO beginning on March 26, 2020. It is currently visible in the southern hemisphere’s morning sky, already as bright as 5th magnitude and visible to the unaided eye; it is traveling northward, en route to perihelion passage (at a heliocentric distance of 0.43 AU) on May 27, and becomes accessible from the northern hemisphere around the middle of May when it may be as bright as 4th magnitude although it will remain close to the eastern horizon before dawn. Comet SWAN will be in conjunction with the sun (25 degrees north of it) on May 26 and thereafter technically becomes an evening-sky object, although its elongation from the sun remains small and it will soon disappear into twilight.

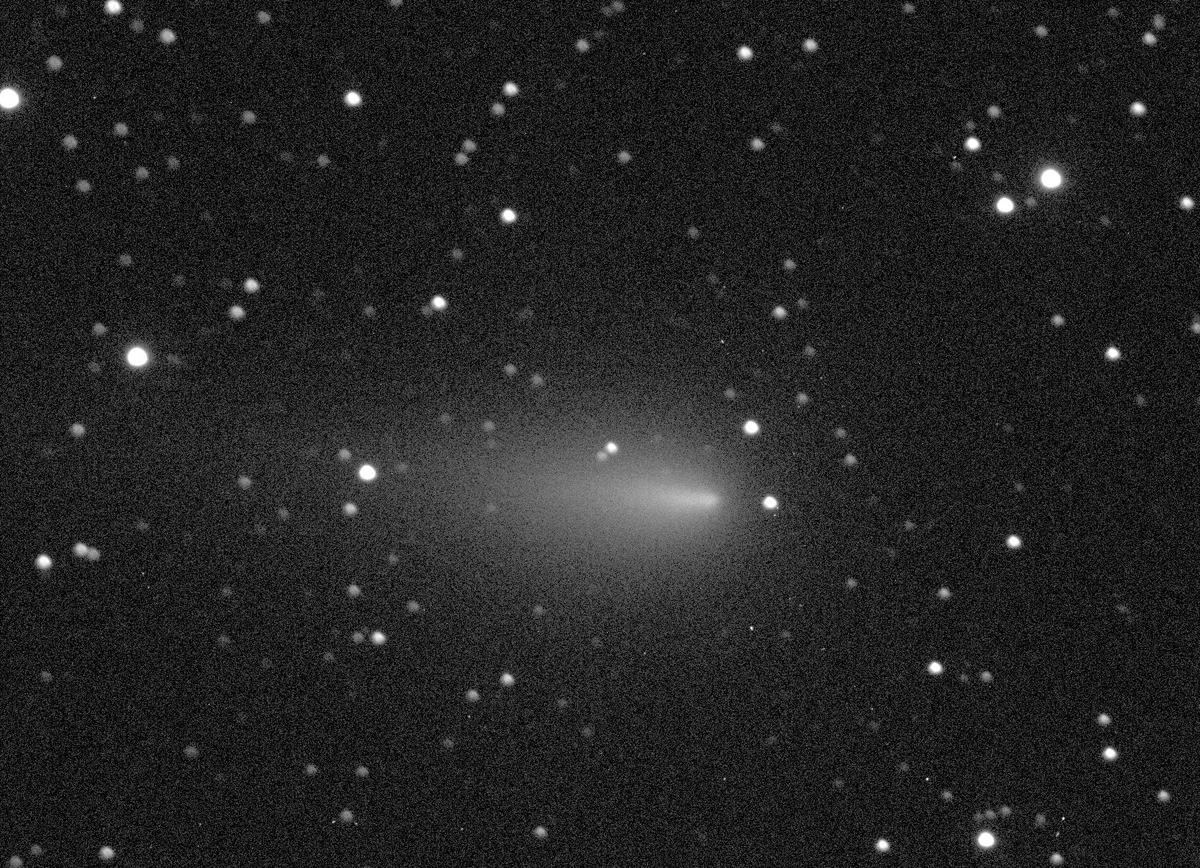

Meanwhile, there is also Comet NEOWISE C/2020 F3, discovered by the NEOWISE mission on March 27, 2020. At present it is about 11th magnitude and best visible from the southern hemisphere, and is traveling northward as it approaches perihelion on July 3 at a heliocentric distance of 0.30 AU. After perihelion, during July it is accessible from the northern hemisphere in the northwestern evening sky, and depending upon how it brightens between now and then there is a possibility that it could be at least somewhat bright. Furthermore, it will be appearing at a moderately high phase angle, and if there is any kind of substantial dust tail there could be some brightness enhancement due to forward scattering of sunlight. It so happens that Comet NEOWISE will be closest to Earth (0.69 AU) on July 23, i.e., the 25th anniversary of the Hale-Bopp discovery, and thus it is least somewhat possible that there could be a moderately bright comet in the sky to mark this important anniversary of one of the biggest events of my life.

As always, I will attempt to carry updated information about each of these comets, and any others that are bright enough for visual observations, at the Comet Resource Center of the Earthrise web site.

More from Week 19:

This Week in History Special Topic Free PDF Download Glossary

Ice and Stone 2020 Home Page