Perihelion: 1997 April 1.14, q = 0.914 AU

This week’s “Special Topics” presentation discusses, among other things, how the practice of discovering comets has changed over the years. Up until a couple of decades ago a rather large percentage of the known comets were discovered by amateur astronomers regularly scanning the skies with relatively small telescopes in deliberate search attempts, and several comet hunters scored multiple successes. Ever since I first began observing comets I had wanted to discover one, and I accordingly engaged in this practice myself, especially during the latter years of the 1980s, but as time went by and I continued to be unsuccessful in this quest, and as my career and family responsibilities began to increase, I began to grow discouraged, and in the early 1990s, after racking up 400 hours of unsuccessful hunting for comets, I gave up the effort. Then, three years later, I ended up discovering one accidentally. I’m not sure if there is a lesson there or not . . .

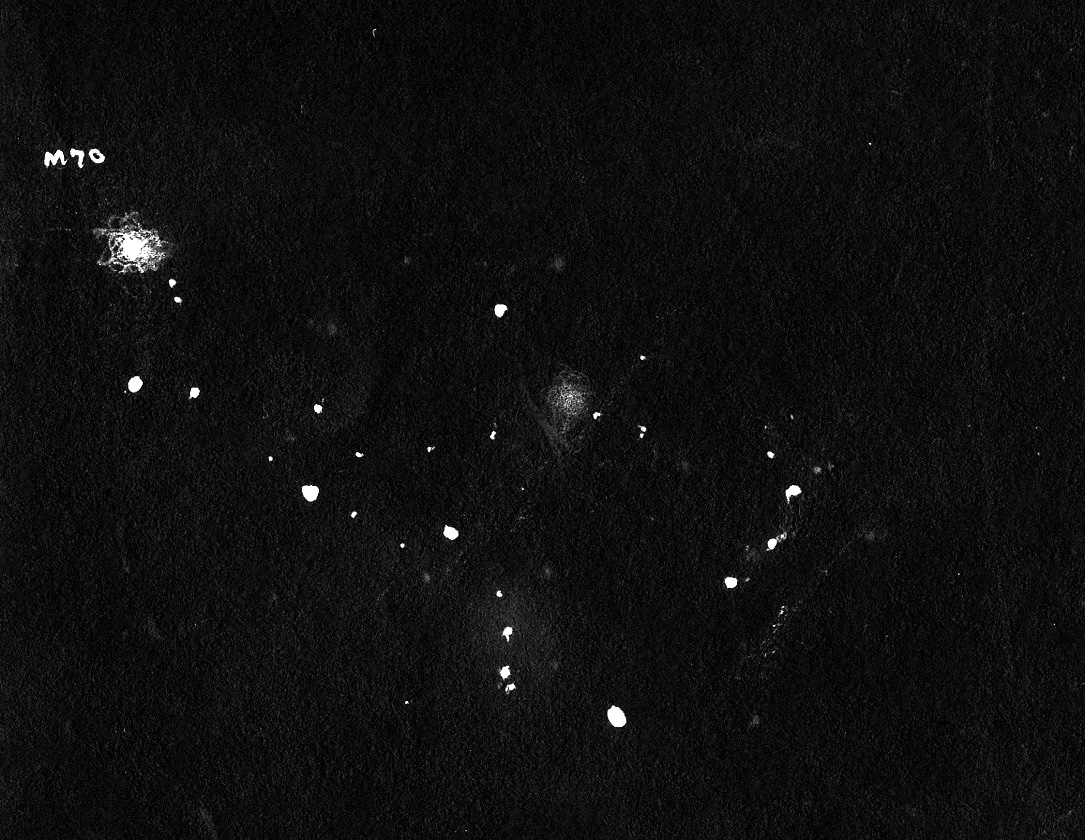

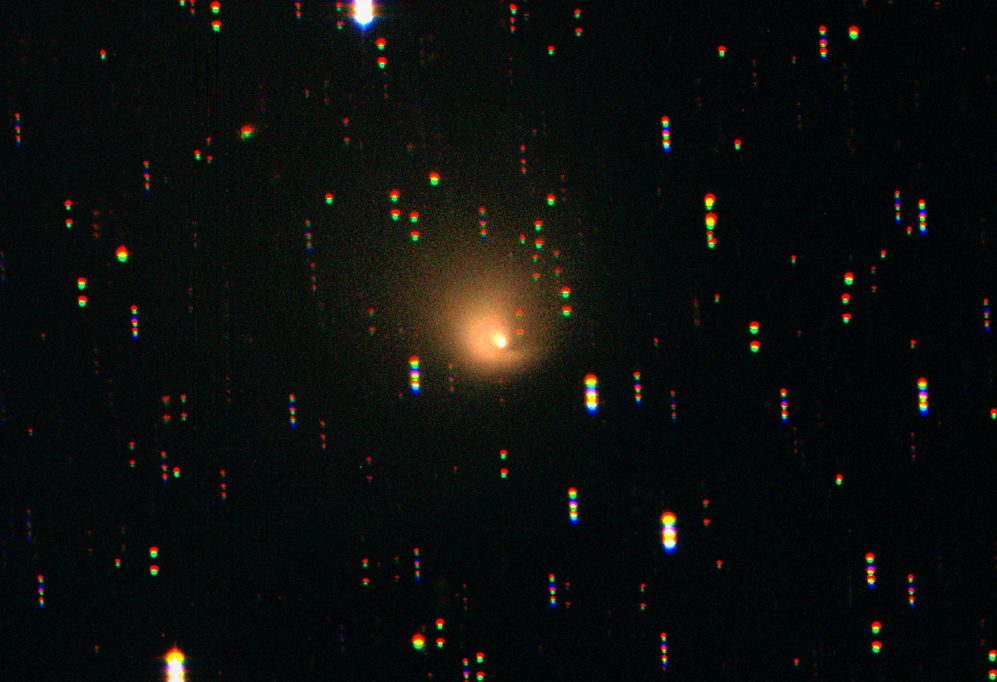

Throughout all that time, and afterwards, I continued my regular comet observing, and on the night of July 22-23, 1995, I had plans to observe the two comets I was then following, but while taking a break between them I decided to look at some deep-sky objects, and when I turned my telescope towards the globular star cluster M70 in Sagittarius shortly after midnight I noticed a diffuse 11th-magnitude object in the same field of view. Over the course of the next 40 minutes I could tell that this object was moving against the background stars. Meanwhile, in my neighboring State of Arizona, an amateur astronomer named Thomas Bopp was observing the sky with some friends in the desert south of Phoenix, and noticed the same diffuse object. Our respective discoveries were apparently within about five minutes of each other.

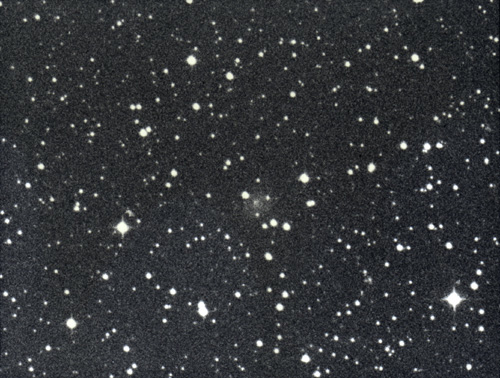

Comet Hale-Bopp was found to be located at the large heliocentric distance of 7.15 AU at the time of its discovery. For a comet at such a distance to be as bright as it was indicated a very high intrinsic brightness, and indeed, intrinsically it is the second-brightest comet ever seen in recorded history (only Comet Sarabat in 1729 was brighter). Once orbital calculations indicated that the comet was still over a year and a half away from perihelion passage, which would take place within 1 AU of the sun, it became apparent that a potential “Great Comet” was on the way. Rob McNaught at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales then located a pre-discovery image of Comet Hale-Bopp on a photographic plate taken at Siding Spring on April 27, 1993 – at which time the comet’s heliocentric distance was 13.1 AU – and this helped establish that the comet was not a first-time visitor from the Oort Cloud, thus adding further grounds for optimism for a bright display.

The comet was followed extensively for the remaining months of 1995, and it remained quite active, occasionally exhibiting small outbursts in its nuclear region, and studies indicated that the activity was being driven by sublimation of carbon monoxide. After being in conjunction with the sun at the beginning of 1996 it emerged into the morning sky in February, being about 9th magnitude at the time. The comet brightened steadily throughout the course of 1996, becoming faintly visible to the unaided eye shortly before mid-year (at which time its heliocentric distance was a little over 4 AU) and being close to magnitude 3.5 at the very end of the year when it was again passing through solar conjunction.

After emerging back into the morning sky in early January 1997 Comet Hale-Bopp brightened rapidly as it made its final approach to perihelion, reaching 1st magnitude in late February and magnitude 0 in early March, when it was successfully observed during the total solar eclipse on March 9 that crossed Mongolia and Siberia. It was nearest Earth (1.32 AU) on March 22, at which time it was also in conjunction with the sun but well north of it, and thereafter became primarily visible in the northwestern evening sky after dusk. During the last couple of weeks of March and first couple of weeks of April the comet reached a peak brightness of magnitude -1 and exhibited a prominent dust tail close to 20 degrees long as well as a prominent ion tail roughly 15 degrees long.

Following perihelion passage the comet traveled southward and began fading, and was lost to the northern hemisphere during the latter part of May. By this time it had become accessible from the southern hemisphere, and was around 2nd magnitude during June (albeit low in the west after dusk). After another conjunction with the sun in early July the comet was again briefly visible from mid-northern latitudes as a 5th– and then 6th-magnitude object low in the southern sky, but dropped permanently below the southern horizon from northern temperate latitudes during the latter part of November. It remained accessible from the southern hemisphere from that point on, with the final naked-eye observations being reported right around that same time. I saw it for the last time on May 26 from New South Wales when it was 9th magnitude, and the last visual observations that I’m aware of were made in early July 2000 – shortly after it had passed directly over the Large Magellanic Cloud – when it was around 14th magnitude. Larger telescopes continued to follow it well after that time, and the comet apparently remained active until 2010, at which time its heliocentric distance was almost 30 AU. The final images as of this writing were taken on August 13, 2013, by Karen Meech and Olivier Hainaut with the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile; at that time its heliocentric distance was 36.4 AU and it appeared as a very faint, stellar object close to 24th magnitude.

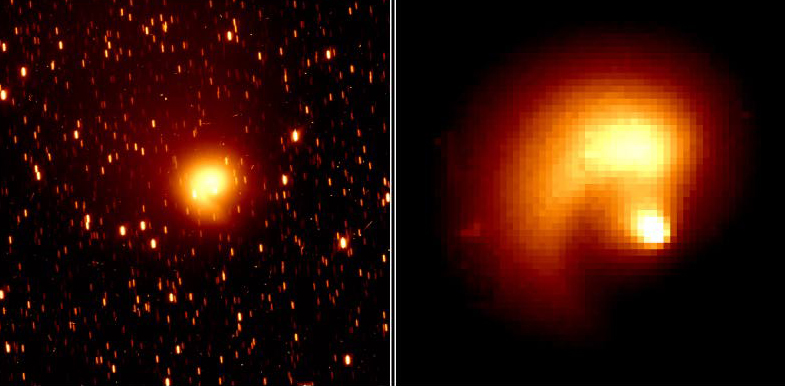

Especially with the long lead time that allowed for detailed observation planning, Comet Hale-Bopp was a scientific boon. Although it never came close enough to Earth for an accurate determination, most studies indicate that Hale-Bopp has a nucleus roughly 40 km in diameter – among the largest on record. Physically, the coma was as large or larger than the sun, and ultraviolet images taken with the Solar Wind ANisotropies (SWAN) telescope aboard the SOlar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft indicate that its Lyman-alpha hydrogen cloud was 2/3 of an AU across. Numerous substances, including several first-time detections of various organic compounds as well as material also found in interstellar dust clouds, were detected within Hale-Bopp, and studies suggest that it – and presumably most if not almost all other long-period comets as well – initially formed in the other solar system between Jupiter and Neptune. One especially interesting scientific result was that the deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio in Hale-Bopp’s water is about twice that of Earth’s seawater – a result consistent with that of some other comets but inconsistent with some others, and which has important implications for Earth’s natural and biological history. This subject is addressed further in a future “Special Topics” presentation.

Comet Hale-Bopp was also very popular with the general public as well, and it can be safely said that it was viewed by more people than any other comet in history. It found its way into numerous movies and episodes of television programs, and quite a few songs about it were written as well – I discuss some of these in a previous “Special Topics” presentation. My life was certainly interesting throughout this time, as I found myself being asked for numerous interviews and public speaking engagements. One of the most memorable events was a private comet-viewing session at the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C. with then-U.S. Vice President Al Gore and his wife.

With over 20 years’ worth of astrometric observations available, it is conceivable that some reasonably valid statements can be made about Comet Hale-Bopp’s past and future. A 2017 study by Rainer Kracht and Zdenek Sekanina suggests that the comet would have previously returned around 2251 B.C.; while it could well have been a bright object at that time, there are no records from that era that can conclusively be tied to it. If Kracht and Sekanina’s predicted perihelion time in early December of that year is accurate, then the comet would have passed very close to Jupiter a little over a year previously, possibly being perturbed from being a first-time visitor from the Oort Cloud into the 4600-year orbit that it occupied thereafter. Meanwhile, in April 1996 while approaching its most recent perihelion Comet Hale-Bopp passed 0.77 AU from Jupiter, which cut its orbital period almost in half. While this should perhaps not be taken too seriously, Kracht and Sekanina predict the next perihelion passage as taking place around August 6, 4393. Regardless of whether or not that prediction is accurate, the comet should certainly be returning sometime within that general timeframe, and presumably should once again be a bright object as it was in 1997. Provided that there is still a human civilization on Earth at that time – and perhaps “Ice and Stone 2020” participating students could have something to say about that – any humans living during that time can once again appreciate the lovely object in their nighttime sky, and it might very well be known by its present name, in turn giving me a type of immortality that few individuals in history have ever achieved.

More from Week 30:

This Week in History Special Topic Free PDF Download Glossary

Ice and Stone 2020 Home Page