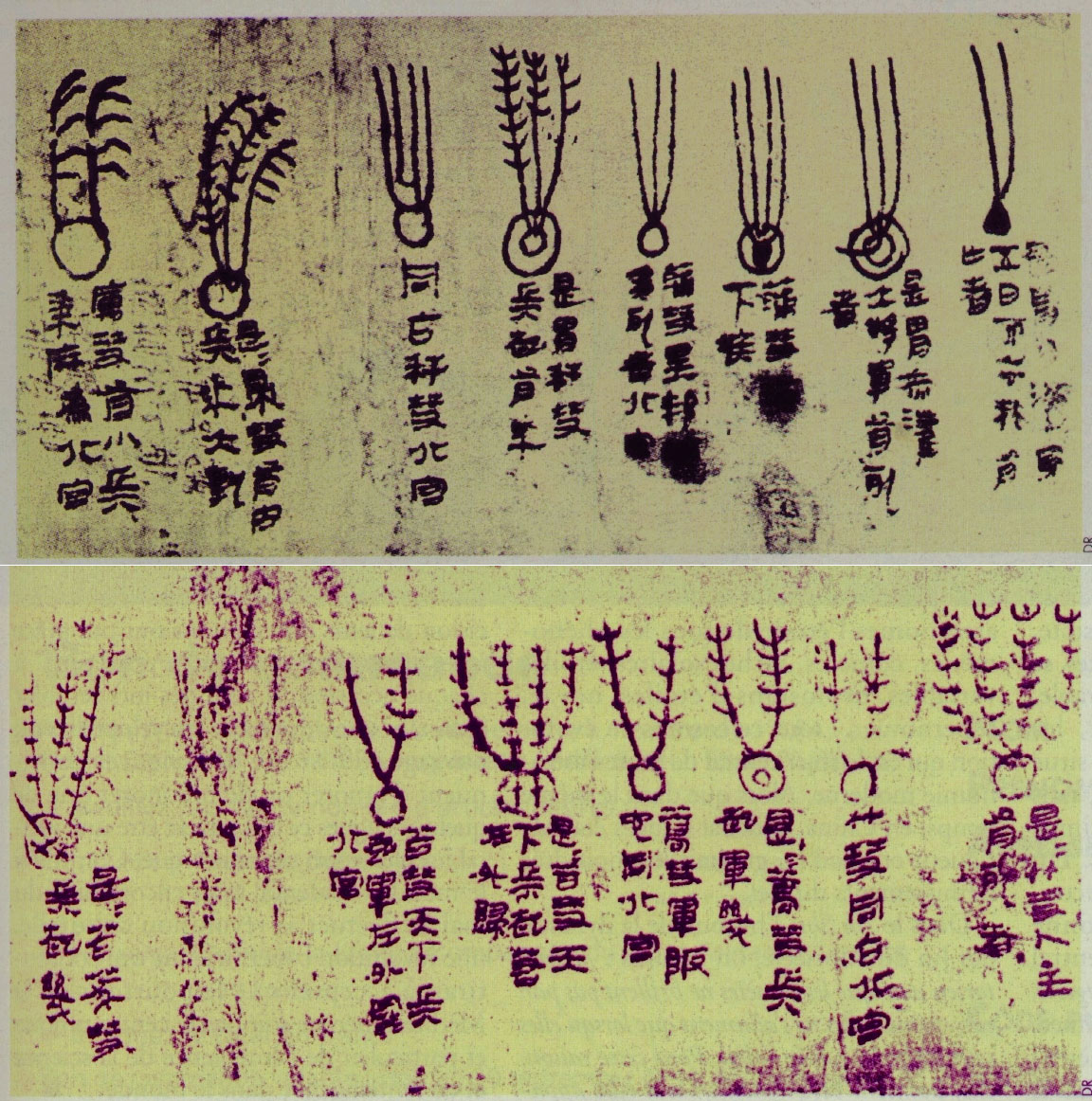

Up until a few centuries ago, all the comets that were seen by human beings were “discovered” via the unaided eye. It is unlikely that there were ever any search efforts for these objects, rather, when they appeared they essentially revealed themselves to the people who were alive at that time. Probably the closest thing to any “search effort” was conducted by the court astronomers of the various Chinese dynasties, who were primarily tasked with watching the skies for anything unusual. They kept relatively detailed records of the comets they observed, indeed, much of what we know about comets that appeared prior to about the year 1600 comes from these records. It should perhaps be kept in mind that for a comet to become noticed to naked-eye observers it probably needs to be at least as bright as 3rd or 4th magnitude.

After the invention of the telescope in the early 17th Century it was inevitable that, eventually, such an instrument would be used to discover comets. The first such discovery took place on November 14, 1680 when a German astronomer, Gottfried Kirch, discovered what would later become the Great Comet of that year (and a future “Comet of the Week”). As the subsequent decades passed more and more comets began to be discovered with telescopes.

What were apparently the first systematic search efforts for comets began during the mid- to late 18th Century and were conducted by French astronomer Charles Messier – best known for the catalogs of deep-sky objects he compiled in order to avoid mistaking them for comets – and his contemporaries like Pierre Mechain and Jacques Montaigne. Caroline Herschel, sister of Uranus discoverer William Herschel, discovered eight comets in the late 18th Century, and another French astronomer, Jean Louis Pons, dominated comet discoveries during the first three decades of the early 19th Century. Among the many successful comet hunters of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, those with the most discoveries include Lewis Swift, Edward Barnard, William R. Brooks, and Charles Perrine in the U.S., and Alphonse Borrelly and Michel Giacobini in France.

The most successful visual comet hunters of the early to mid-20th Century were William Reid in South Africa and Leslie Peltier in the U.S. In 1940 a Japanese amateur astronomer, Minoru Honda, discovered his first comet, and then discovered eleven more up through 1968 (as well as several novae in subsequent years); inspired by their countryman, Japanese amateur astronomers began to devote significant energy towards discovering comets, and dominated the field during the 1960s and 1970s and well into the 1980s, and it was not unusual for comets to have two or three Japanese names assigned to them. During the recent past the most successful visual hunters have been Don Machholz (11 comets between 1978 and 2010) and David Levy (9 comets between 1984 and 2006) in the U.S. and William Bradfield (18 comets between 1972 and 2004) in South Australia; all three of these individuals have previous and/or future “Comets of the Week.”

In addition to all the above-named individuals, there have been numerous others who have swept the sky looking for comets, and who have perhaps one or two comet discoveries to their credit. From time to time there have been the occasional “accidental” discoveries, i.e., a comet that is detected while the discoverer is examining something else; my own discovery of Comet Hale-Bopp C/1995 O1 – this week’s “Comet of the Week” – is a distinct example of this.

All of the earliest known asteroids were also discovered visually, although the first-known one, (1) Ceres, was an accidental discovery. Unlike comets, which can usually be noticed right away due to their large and diffuse comae, asteroids are much more difficult to identify since they appear starlike and can only be detected by their motion against the background stars. Nevertheless, some astronomers were reasonably successful at this endeavor, with the most successful one being Austrian astronomer Johann Palisa, who discovered 122 asteroids between 1874 and 1923.

By the late 19th Century astro-photography was starting to come into its own, and asteroids were starting to show up on photographic plates so often that one astronomer of that era referred to them as the “vermin of the skies.” Among the more successful asteroid discoverers who utilized photography was the German astronomer Max Wolf, who discovered 248 asteroids between 1891 and 1932.

The first comet to be discovered via photography was found by American astronomer Edward Barnard on October 13, 1892, who accidentally discovered it on a 4-hour exposure he took of a Milky Way star field near the star Altair in the constellation Aquila. The comet – about 12th magnitude at the time of its discovery – was found to be of short period, however it was lost until it was re-discovered in 2008 by Andrea Boattini with the Catalina Sky Survey – see below – and it is now known as Comet 206P/Barnard-Boattini.

Beginning in the late 19th Century various observatories around the world engaged in photographic patrol programs for comets and asteroids, and many of these made quite a few discoveries of these objects. One of the more notable of these was the one conducted at Lowell Observatory in Arizona beginning in 1929 and which utilized wide-field photographic plates; as discussed in last week’s “Special Topics” presentation this was specifically instituted to look for Percival Lowell’s “Planet X” and it was during the course of this survey that Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto the following year. The survey continued for another decade afterward, and netted many asteroid discoveries as well as two comets, although both of these were not recognized until many months after the fact and had become lost. Both of these comets have now been identified with periodic comets discovered during the relatively recent past.

One interesting variation of the various observatory-run survey programs was a visual survey for comets conducted at Skalnate Pleso Observatory in then-Czechoslovakia (present-day Slovakia) from the mid-1940s to the late 1950s. The program resulted in several comet discoveries during that period, with one of the individuals involved, Antonin Mrkos, discovering 11 comets. His brightest one, Comet Mrkos 1957d, is a future “Comet of the Week.”

A Schmidt telescope is an instrument invented in 1930 by German-Estonian optician Bernhard Schmidt specifically designed to take wide-field photographs of large areas of the sky. One of the earliest and most productive Schmidt telescopes was one with a 1.2-meter aperture constructed at Palomar Observatory in California in the late 1940s, and in an effort partially funded by the National Geographic Society between 1949 and 1955 this instrument carried out a detailed survey of the entire sky visible from California. Many asteroids and over a dozen comets were discovered during the course of this “Palomar Sky Survey,” and the digitized version of the survey images remains one of the most useful tools in astronomy today. A southern hemisphere version of the Palomar Sky Survey was conducted with a similar-size Schmidt telescope located at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales during the 1970s, and a second-generation Palomar Sky Survey was conducted with the Schmidt telescope at Palomar from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s; both of these surveys also produced numerous asteroid and comet discoveries.

These and other Schmidt telescopes at various observatories around the world have been utilized for survey efforts on a rather frequent basis, and indeed the Palomar Schmidt has yielded numerous asteroid and comet discoveries over the years, including the first-known centaur, (2060) Chiron, in 1977. (See the “Special Topics” presentation on centaurs.) A smaller Schmidt telescope, with an aperture of 46 cm, has also been constructed at Palomar, and planetary geologist Eugene Shoemaker conducted a survey program with this instrument from 1982 to 1994 that netted 32 comet discoveries as well as numerous asteroids; one of the comets was Shoemaker-Levy 9 – last week’s “Comet of the Week” – which impacted Jupiter in 1994. Astronomer Eleanor Helin conducted a similar survey program with this same telescope during that same timeframe and also made discoveries of several comets and asteroids.

The invention of the charge-coupled device, or CCD, which utilizes electronic computer chips instead of film for its recording surface, in the late 1960s has revolutionized just about every facet of astronomy. CCDs, which are far more efficient than photographic emulsions and thus can reach fainter magnitudes in a much shorter span of time, began to be utilized for astronomy in 1980, and the recovery of Comet 1P/Halley in 1982 with a CCD attached to the 5.1-meter Hale Telescope at Palomar Observatory was an early and powerful demonstration of their capabilities.

It would only be a matter of time before CCDs would be utilized for search efforts for asteroids and comets. The earliest CCD chips were quite small and thus couldn’t cover a very large field, although their efficiency and short exposure time made up for this. The first CCD survey program was Spacewatch, the brainchild of astronomer Tom Gehrels (who had utilized the 1.2-meter Palomar Schmidt telescope to make discoveries of several comets and near-Earth asteroids), which went on-line at Kitt Peak Observatory in Arizona in late 1983 with a 0.9-meter telescope. Initially, Spacewatch was pretty much limited to recoveries of expected periodic comets, but with the installation of a larger chip in late 1989 it began discovering faint near-Earth asteroids almost right away. Spacewatch found its first comet – the first ever discovered via CCD – on September 8, 1991, a very faint periodic object now known as Comet 125P/Spacewatch. The Spacewatch program continues operating today, and has undergone numerous upgrades including larger and more efficient computer chips as well as the addition of a 1.8-meter telescope; it has racked up quite a few discoveries, including the Apollo-type asteroid now known as (35396) 1997 XF11 which, as discussed in a previous “Special Topics” presentation, created quite a stir when orbital calculations were indicating a very close approach to Earth in 2028.

The impacts of the fragments of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 into Jupiter in July 1994 generated a lot of public interest in the potential threat due to impacts by comets and asteroids, and among other things led to the chartering of a commission led by Eugene Shoemaker – one of that comet’s co-discoverers – and tasked with recommending appropriate courses of action to counter that threat. The Shoemaker Commission’s strongest recommendation was the development of comprehensive survey programs to search for and identify potentially threatening objects well in advance, and with CCD imaging starting to come into its own, along with the continuing improvements in computer technology, the time was ripe for the first such survey efforts to become operational.

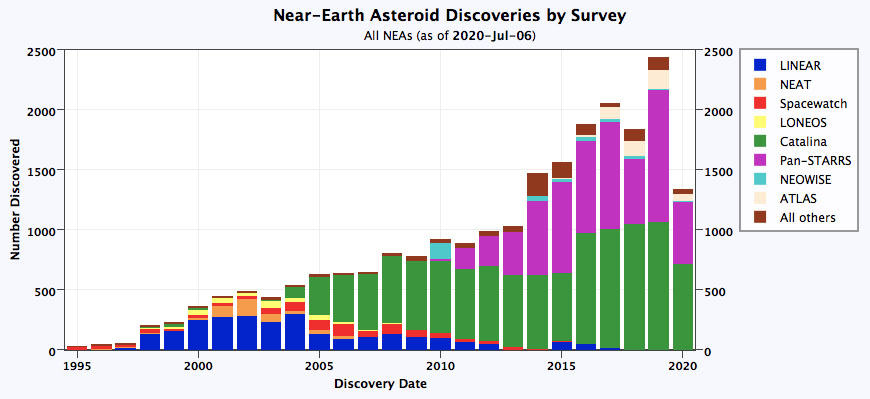

The first comprehensive survey was the LIncoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research (LINEAR) program, developed by Grant Stokes at Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Lincoln Laboratory and which utilized funding from the U.S. Air Force to develop the large computer chip used for the imaging. The chip was placed on a 1-meter Ground-based Electro-Optical Deep Space Surveillance (GEODSS) telescope located at Lincoln Laboratory’s Experimental Test Station near the northern end of White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, and after tests that were conducted in mid-1996 and again in 1997 – during which approximately twenty near-Earth asteroids were discovered – LINEAR went fully on-line in March 1998.

At that time the field of near-Earth asteroid discovery changed almost overnight, as LINEAR began reporting discoveries of such objects on almost a nightly basis. Before long, almost all other discovery programs were rendered all but obsolete, and LINEAR dominated the field for the next several years, although eventually additional survey programs (discussed below) became operational and began making their own discoveries. LINEAR also dominated the discoveries of comets and main-belt asteroids as well, and by the time it was shut down at the end of 2012 LINEAR had discovered over 200 comets, over 2400 near-Earth asteroids, and over 140,000 main-belt asteroids. Among its discoveries were the first bright naked-eye comet of the 21st Century, Comet C/2001 A2 (a previous “Comet of the Week”), and the first confirmed Atira-type asteroid – (163693) Atira – in February 2003.

Following the termination of the initial survey LINEAR’s efforts turned toward testing of a 3.5-meter Space Surveillance Telescope on an adjacent site at White Sands Missile Range for a few years during the mid-2010s, during which time it discovered a handful of additional comets and near-Earth asteroids. This instrument is currently scheduled to be deployed to Exmouth, Western Australia, and to become operational in 2021, and although its primary mission is the search for artificial space debris, it will likely discover more comets and near-Earth asteroids in the process.

Another early comprehensive survey effort was the Near-Earth Asteroid Tracking (NEAT) program developed by Eleanor Helin. An early incarnation of NEAT went on-line in late 1995 and utilized a 1-meter GEODSSS telescope based at Mount Haleakala in Hawaii, and over the next 3½ years it discovered approximately 30 near-Earth asteroids, two comets, and the first-known long-period “Damocloid” object, 1996 PW. (These objects are discussed in a future “Special Topics” presentation.) After this initial effort was terminated in mid-1999 a more comprehensive version became operational in mid-2000 which involved both a 1.2-meter GEODSS telescope at Haleakala as well as the refitted 1.2-meter Schmidt telescope at Palomar. During the subsequent six years NEAT discovered several hundred near-Earth asteroids and over fifty comets.

One other productive early comprehensive survey effort was the Lowell Observatory Near-Earth Object Search (LONEOS) program, which utilized a 0.6-meter Schmidt telescope located at Lowell Observatory’s Anderson Mesa station outside of Flagstaff, Arizona, and which initially went on-line in 1993, expanded its capability in 1998, and terminated in 2008. During its years of operation LONEOS discovered approximately 22,000 main-belt asteroids, almost 300 near-Earth asteroids, and 40 comets.

For the past decade and a half, one of the most productive survey programs is the Catalina Sky Survey based in Arizona which, after some earlier smaller efforts in the mid- to late 1990s, became fully operational in 2004. The Catalina survey utilizes a 0.7-meter telescope located on Mount Bigelow near Tucson, and the Mount Lemmon Survey, which operates under the same management, utilizes a 1.5-meter telescope on that peak. As of now the Catalina and Mount Lemmon surveys have discovered several thousand near-Earth asteroids and over 200 comets.

Between 2004 and mid-2013 (at which time funding was terminated) the Catalina survey program also managed the Siding Spring Survey that was based at the namesake observatory in New South Wales. During that time it was the only comprehensive survey program based in the southern hemisphere, and it discovered several hundred near-Earth asteroids and slightly over 100 comets, three-fourths of these being made by Rob McNaught. Two of the survey’s most important discoveries were Comet McNaught C/2006 P1 – a previous “Comet of the Week” – which was the 21st Century’s first “Great Comet,” and Comet Siding Spring C/2013 A1 – a future “Comet of the Week” – that passed extremely close to Mars in October 2014. Following the survey’s termination there has not yet been another comprehensive survey program in the southern hemisphere.

The most comprehensive survey program operating at this time is the Panoramic Survey Telescope And Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS) program run by the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii and based on Mount Haleakala. Pan-STARRS, which became operational in 2010, utilizes a 1.8-meter telescope (as well as a second telescope of the same size that has been operational since 2015) and since then has discovered several thousand near-Earth asteroids and over 200 comets. What can be considered as Pan-STARRS’s most important discovery is the interstellar object 1I/’Oumuamua in 2017, which is the subject of a future “Special Topics” presentation.

Two other productive survey programs that are operating at this time are the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) program based in Hawaii and the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) program based in California. ATLAS, which went on-line in 2015, utilizes two 50-cm telescopes, one based at Haleakala and the other based on Mauna Loa, and has to date discovered over 450 near-Earth asteroids and 48 comets, including Comet ATLAS C/2019 Y4, a previous “Comet of the Week.” The ZTF program, which utilizes the again-refitted 1.2-meter Schmidt telescope at Palomar, became operational in early 2018, and although it looks for transient phenomena both within and outside the solar system, has discovered a handful of comets and near-Earth asteroids, including the three Atira-type asteroids with the smallest-known orbits (2019 AQ3, 2019 LF6, and 2020 AV2, the last of these being the first-known asteroid to travel entirely within the orbit of Venus).

Over the recent years several smaller-scale survey programs have also been successful at discovering comets and near-Earth asteroids. There have also been a couple of space-based survey programs, which, like the ZTF, have searched for phenomena both within and outside the solar system. During the ten months it was operational in 1983 the InfraRed Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) spacecraft discovered six comets, including the Earth-grazing Comet IRAS-Araki-Alcock 1983d – a previous “Comet of the Week” – and a few near-Earth asteroids, including (3200) Phaethon which appears to be the parent object of the Geminid meteor shower and which may have been an active comet in the past. (Phaethon is discussed in more detail in future “Special Topics” presentations.) The Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) spacecraft launched in late 2009 discovered 17 comets and several dozen near-Earth asteroids before its superfluid helium coolant ran out in early 2011; among its discoveries was the first-known – and so far only known – “Earth Trojan” asteroid, 2010 TK7. (Trojan asteroids are the subject of a future “Special Topics” presentation.) Two of WISE’s detectors remained operational, and in 2013, under the mission name Near-Earth Object Wide-Field Survey Explorer (NEOWISE), WISE was reactivated to search for Earth-approaching asteroids, and to date has found approximately 200 such objects as well as 15 comets, including Comet NEOWISE C/2020 F3 which is currently a bright object in our nighttime sky and which is next week’s “Comet of the Week.”

At this time the most active and productive survey programs are the Catalina and Mount Lemmon surveys, Pan-STARRS, ATLAS, ZTF, and NEOWISE. If things go as planned, they will soon be joined by a larger effort: the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) – recently renamed the Vera Rubin Observatory– a large 8.4-meter telescope that will be based in northern Chile. Construction of the Rubin Observatory telescope began in 2015 and it is expected to see “first light” this year, with full operations commencing in early 2022. The plan is for the Rubin Observatory to produce a ten-year-long survey wherein it will image the entire nighttime sky (visible from Chile) down to 24th magnitude every few nights, and the data will immediately become accessible to the public.

In the face of all the current and expected survey programs, it would seem that there is not a lot of room left for possible discoveries by amateur astronomers. Indeed, it has appeared for some time that the era of visual comet discoveries is all but over, although in November 2018 Don Machholz visually discovered his twelfth comet – the first visual comet discovery from anywhere in the world in eight years. Whether or not he, or anyone else, will ever find another comet in such a manner – especially once the Rubin Observatory survey becomes operational – remains to be seen.

It should be noted that two Japanese amateur astronomers, Shigehisa Fujikawa and Masayuki Iwamoto, independently discovered Machholz’s comet at the same time with CCDs, and in fact Iwamoto discovered another comet just barely over a month later and then another one early this year. Indeed, several amateur astronomers have had successful discovery efforts with their own CCD and/or digital camera systems, one of these being the Southern Observatory for Near-Earth Asteroids Research (SONEAR) program run by several amateur astronomers in Brazil which has helped fill in the gap left by the termination of the Siding Spring Survey and which has discovered over 30 near-Earth asteroids and nine comets. Terry Lovejoy in Queensland has discovered six comets with his system; three of these became naked-eye objects, and two of these are future “Comets of the Week.” Then there is Gennady Borisov in the Crimea, who has specialized in searching for objects at small elongations from the sun; in addition to some near-Earth asteroids he has discovered nine comets, including the recent interstellar Comet 2I/Borisov I/2019 Q4 – another future “Comet of the Week.” Perhaps, then, there is still room for contributions from amateur astronomers and other aficionados of the nighttime sky.

More from Week 30:

This Week in History Comet of the Week Free PDF Download Glossary

Ice and Stone 2020 Home Page