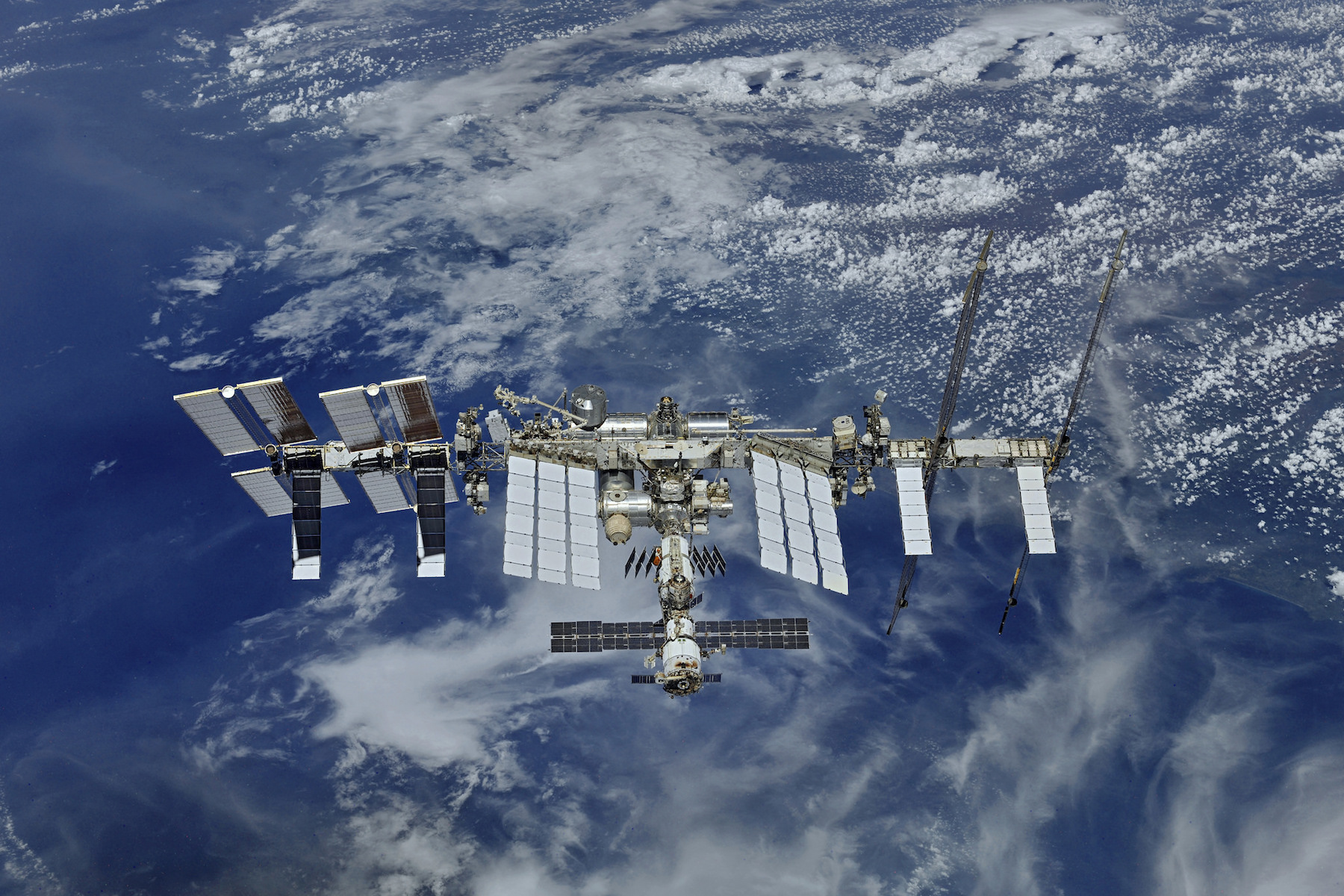

November 2 marked 20 years since the first residents arrived on the International Space Station (ISS). The orbiting habitat has been continuously occupied ever since.

Twenty straight years of life in space makes the ISS the ideal “natural laboratory” to understand how societies function beyond Earth.

The ISS is a collaboration between 25 space agencies and organisations. It has hosted 241 crew and a few tourists from 19 countries. This is 43% of all the people who have ever travelled in space.

As future missions to the Moon and Mars are planned, it’s important to know what people need to thrive in remote, dangerous and enclosed environments, where there is no easy way back home.

A brief history of orbital habitats

The first fictional space station was Edward Everett Hale’s 1869 “Brick Moon”. Inside were 13 spherical living chambers.

In 1929, Hermann Noordung theorised a wheel-shaped space station that would spin to create “artificial” gravity. The spinning wheel was championed by rocket scientist Wernher von Braun in the 1950s and featured in the classic 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Instead of spheres or wheels, real space stations turned out to be cylinders.

The first space station was the USSR’s Salyut 1 in 1971, followed by another six stations in the Salyut programme over the next decade. The USA launched its first space station, Skylab, in 1973. All of these were tube-shaped structures.

The Soviet station Mir, launched in 1986, was the first to be built with a core to which other modules were added later. Mir was still in orbit when the first modules of the International Space Station were launched in 1998.

Mir was brought down in 2001, and broke up as it plummeted through the atmosphere. What survived likely ended up under 5000 meters of water at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

The ISS now consists of 16 modules: four Russian, nine US, two Japanese, and one European. It’s the size of a five-bedroom house on the inside, with six regular crew serving for six months at a time.

Adapting to space

Yuri Gagarin’s voyage around Earth in 1961 proved humans could survive in space. Actually living in space was another matter.

Contemporary space stations don’t spin to provide gravity. There is no up or down. If you let go of an object, it will float away. Everyday activities like drinking or washing require planning.

Spots of “gravity” occur throughout the space station, in the form of hand or footholds, straps, clips, and Velcro dots to secure people and objects.

In the Russian modules, surfaces facing towards Earth (“down”) are coloured olive-green while walls and surfaces facing away from Earth (“up”) are beige. This helps crew to orient themselves.

Colour is important in other ways, too. Skylab, for example, was so lacking in colour that astronauts broke the monotony by staring at the coloured cards used to calibrate their video cameras.

In movies, space stations are often sleek and clean. The reality is vastly different.

The ISS is smelly, noisy, messy, and awash in shed skin cells and crumbs. It’s like a terrible share house, except you can’t leave, you have to work all the time and no-one gets a good night’s sleep.

There are some perks, however. The Cupola module offers perhaps the best view available to humans anywhere: a 180-degree panorama of Earth passing by below.

‘A microsociety in a miniworld’

The crew use all kinds of objects to express their identities in this miniworld, as space habitats were called in a 1972 report. Unused wall space becomes like your refrigerator door, covered with items of personal and group significance.

In the Zvezda module, Orthodox icons and pictures of space heroes like Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and Gagarin create a sense of belonging and connection to home.

Food plays a huge role in bonding. Rituals of sharing food, celebrating holidays and birthdays, help form camaraderie between crew of different national and cultural backgrounds.

It’s not all plain sailing. In 2009, toilets briefly became a source of international conflict when decisions on the ground meant Russian crew were forbidden to use the US toilets and exercise equipment.

In this “microsociety”, technology isn’t only about function. It plays a role in social cohesion.

The future of living in space

The ISS is massively expensive to run. NASA’s costs alone are US$3-4 billion a year, and many argue it’s not worth it. Without more commercial investment, ISS may be de-orbited in 2028 and sent to the ocean floor to join Mir.

The next stage in space-station life is likely to occur in orbit around the Moon. The Lunar Gateway project, planned by a group of space agencies led by NASA, will be smaller than the ISS. Crews will live on board for up to a month at a time.

Its modules, based on the design of the ISS, are due to be launched into lunar orbit in the next decade.

One preliminary habitat design for the Lunar Gateway has four expandable crew cabins, to give people a little more space. But the sleeping, exercise, latrine, and eating areas are all much closer together.

Since ISS crews like to create improvised visual displays, we might suggest including spaces reserved for such displays in next-generation habitats.

In popular culture, the ISS has become Santa’s sleigh. In recent years, parents around the world have taken their children outside on Christmas Eve to spot the ISS passing overhead.

The ISS has shaped the space culture of the 20th and 21st centuries, symbolising international cooperation after the Cold War. It still has much to teach us about how to live in space.![]()

This article was authored by Alice Gorman and Justin St. P. Walsh. It is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.