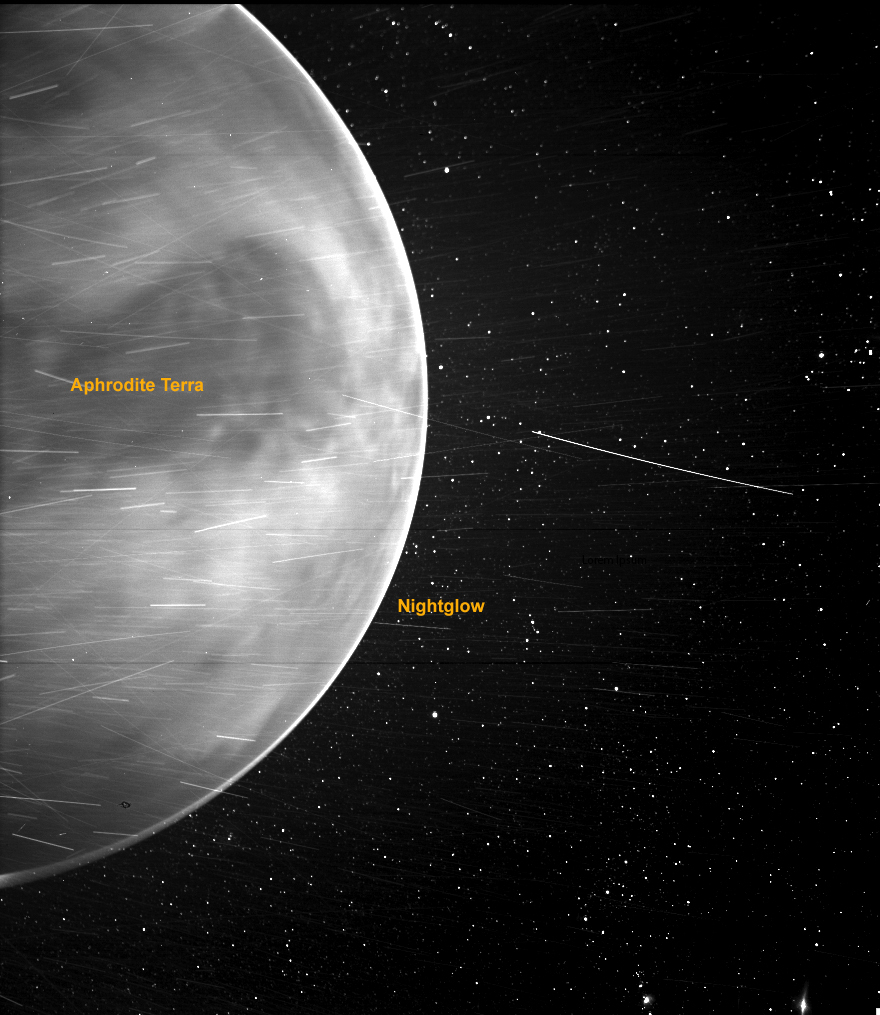

The Parker Solar Probe captured an absolutely stunning glimpse of Venus during its third close flyby of the planet in July 2020, as seen in a newly released image from NASA and the mission’s science team.

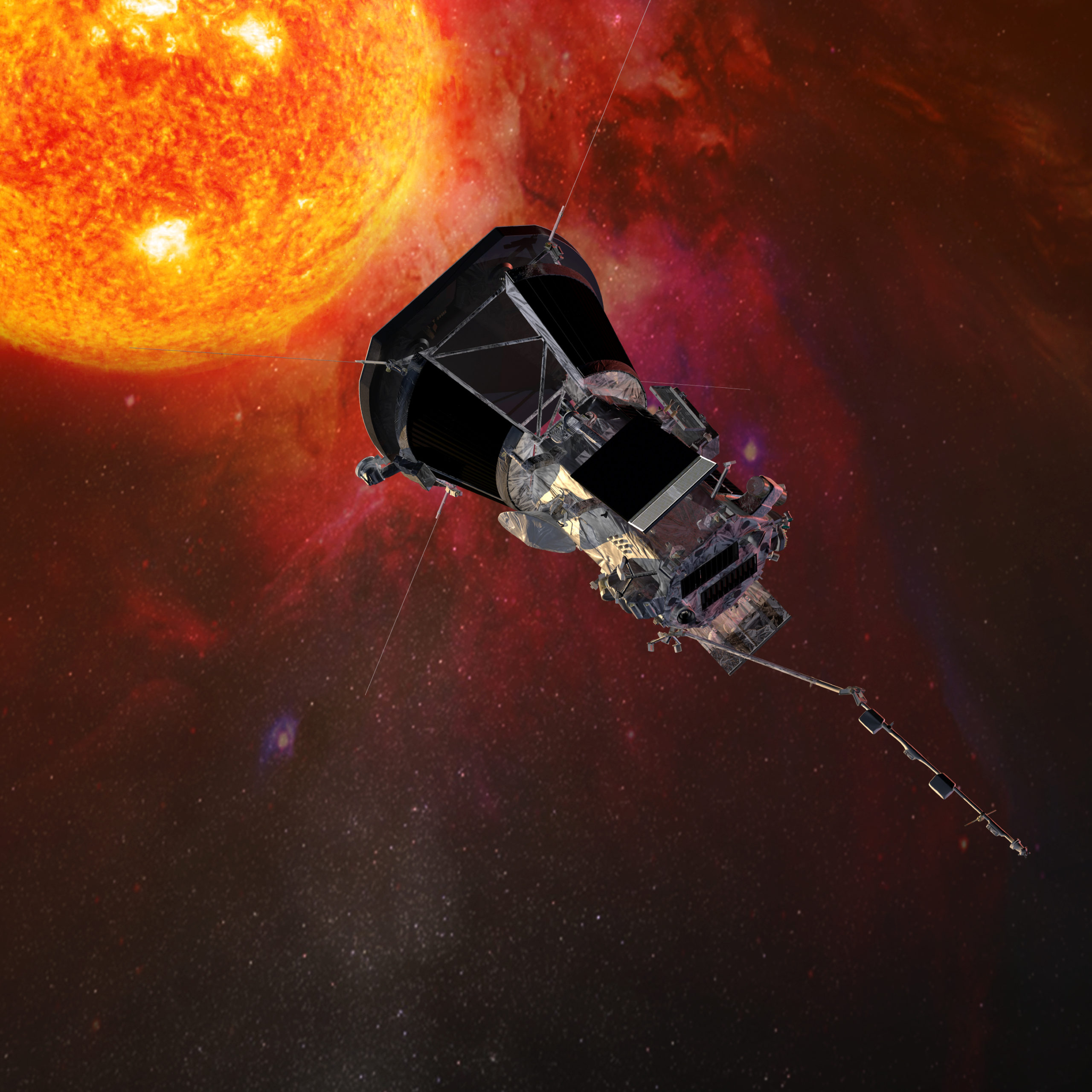

Although the Sun is the focus of the Parker Solar Probe’s seven-year-long mission to “touch” the Sun and fly through the solar corona for unprecedented science gathering operations, she needs to whip past Venus on seven targeted flyby’s as gravity assists to bend the spacecraft’s orbit and fly closer and closer to the Sun to carry out its research goals to study the dynamics of the solar wind at unprecedented close range to its source.

Meanwhile Parker also just completed its fourth flyby of Venus on Feb. 20 since launching two and a half years ago in Aug. 2018.

“But — along with the orbital dynamics — these passes can also yield some unique and even unexpected views of the inner solar system,” said the team in a statement.

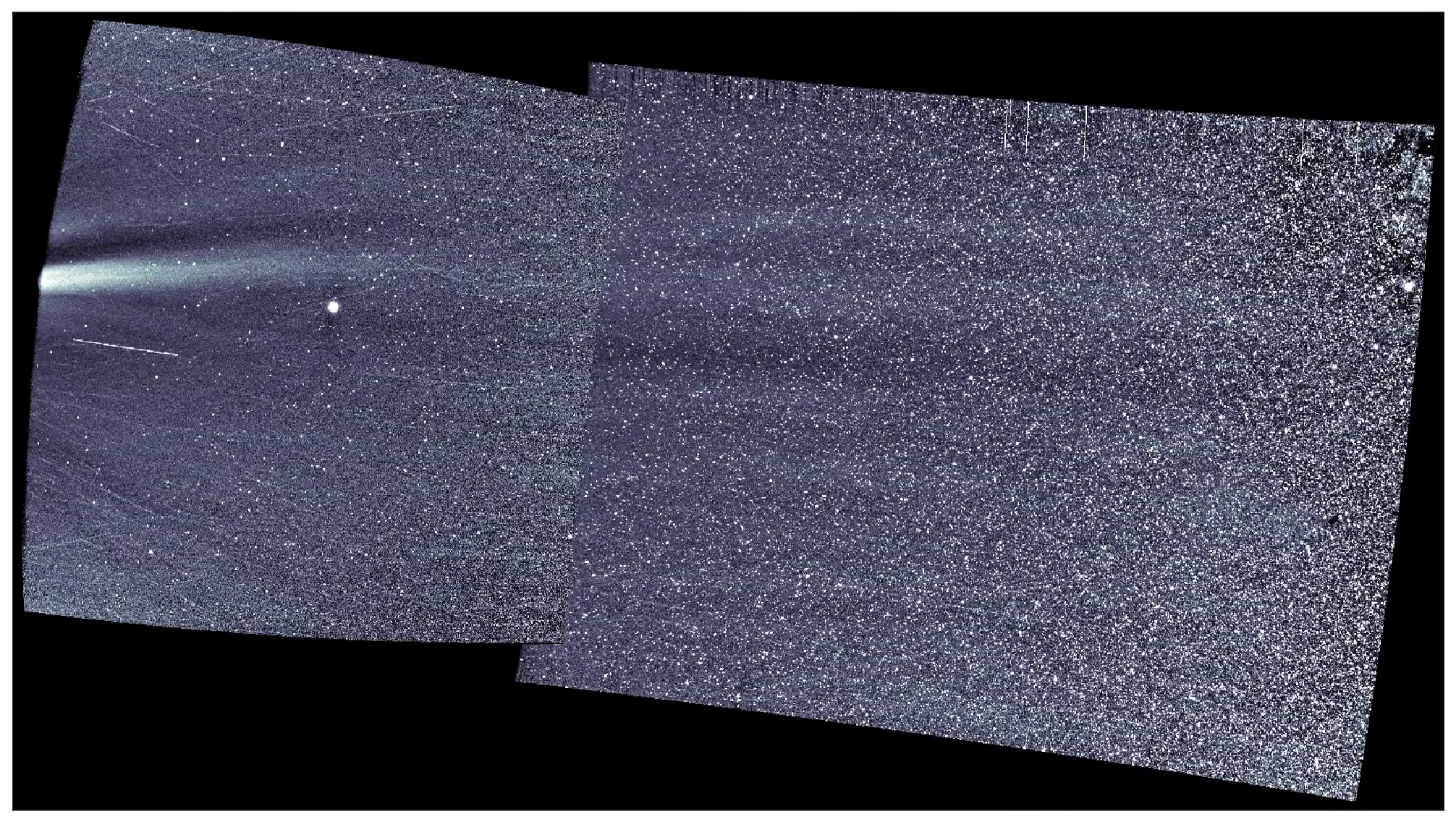

“During the mission’s third Venus gravity assist on July 11, 2020, the onboard Wide-field Imager for Parker Solar Probe, or WISPR, captured a striking image of the planet’s nightside from 7,693 miles [12,309 km] away.”

Look closely at the center of the image and you can see a prominent dark feature named Aphrodite Terra which is the largest highland region on the Venusian surface.

Aphrodite Terra appears dark because of its lower temperature, about 85 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius) cooler than its surroundings.

WISPR also detected “a bright rim around the edge of the planet that may be nightglow — light emitted by oxygen atoms high in the atmosphere that recombine into molecules in the nightside.”

“#ParkerSolarProbe captured this stunning view of Venus during its close flyby of the planet in July 2020. The image shows a bright rim around the planet’s edge, thought to be nightglow, and the dark shape of Aphrodite Terra, a highland on Venus’ surface,” the PSP team said via twitter.

“Parker Solar Probe flies by Venus to perform gravity assist maneuvers — designed to draw its orbit closer to the Sun — a total of seven times throughout its mission.”

The team was surprised to see Venusian surface features with WISPR.

“WISPR is tailored and tested for visible-light observations. We expected to see clouds, but the camera peered right through to the surface,” said Angelos Vourlidas, the WISPR project scientist from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, who coordinated a WISPR imaging campaign with Japan’s Venus-orbiting Akatsuki mission.

See below an annotated version of Venus as seen by WISPR.

The WISPR instrument “is designed to take images of the solar corona and inner heliosphere in visible light, as well as images of the solar wind and its structures as they approach and fly by the spacecraft.”

“WISPR effectively captured the thermal emission of the Venusian surface,” said Brian Wood, an astrophysicist and WISPR team member from the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C.

“It’s very similar to images acquired by the Akatsuki spacecraft at near-infrared wavelengths.”

This surprising observation sent the WISPR team back to the lab to measure the instrument’s sensitivity to infrared light, said NASA. If WISPR can indeed pick up near-infrared wavelengths of light, the unforeseen capability would provide new opportunities to study dust around the Sun and in the inner solar system. If it can’t pick up extra infrared wavelengths, then these images — showing signatures of features on Venus’ surface — may have revealed a previously unknown “window” through the Venusian atmosphere.

“Either way,” Vourlidas said, “some exciting science opportunities await us.”

During the fourth of the seven planned Venus gravity assists this past week on Feb 20, Parker Solar Probe was set up “for its eighth and ninth close passes by the Sun, slated for April 29 and Aug. 9. During each of those passes, Parker Solar Probe will break its own record when it comes approximately 6.5 million miles (10.4 million kilometers) from the solar surface, about 1.9 million miles closer than the previous closest approach – or perihelion – of 8.4 million miles (13.5 million kilometers) on Jan. 17, wrote Mike Buckley in a mission blog.

“At just after 3:05 p.m. EST, moving about 54,000 miles per hour (about 86,900 kilometers per hour), the spacecraft will pass 1,482 miles (2,385 kilometers) above Venus’ surface as it curves around the planet. Such Venus gravity assists are essential to the mission to bring the spacecraft close to the Sun; Parker Solar Probe relies on the planet to reduce its orbital energy, which in turn allows it to travel closer to the Sun – and inspect the properties of the solar wind closer to its source.”

Parker is equipped with four onboard science instrument suites.

The key goals are to try and answer fundamental questions about the nature of the Sun and develop an understanding of how the Sun works – such as why is the solar corona so hot. It’s much hotter than the Sun’s surface.

Scientists also want to know why the solar wind is accelerated to supersonic speeds.

The mission will conduct set Venus flybys to set up 24 perihelion close encounters with the Sun through 2024. The Venus flybys will precisely set its trajectory toward the Sun and slow the probe down instead of speeding it up.

The $1.5 Billion mission began with a dazzling middle-of-the-night blastoff of the mighty Delta IV Heavy rocket in the wee hours of the morning, Aug. 12, 2018 – and delivered the car-sized spacecraft to its intended trajectory towards Venus and the Sun.

The 23-story tall triple barreled United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy rocket successfully launched at 3:31 a.m. EDT Aug. 12, 2018, from the Florida Space Coast and put on a brilliant display of firepower with 2.1 million pounds of thrust spewing forth from the trio of liquid oxygen/liquid hydrogen RS-68A main engines that quickly turned night into day a few hours before the natural sunrise under nearly cloud-free skies.