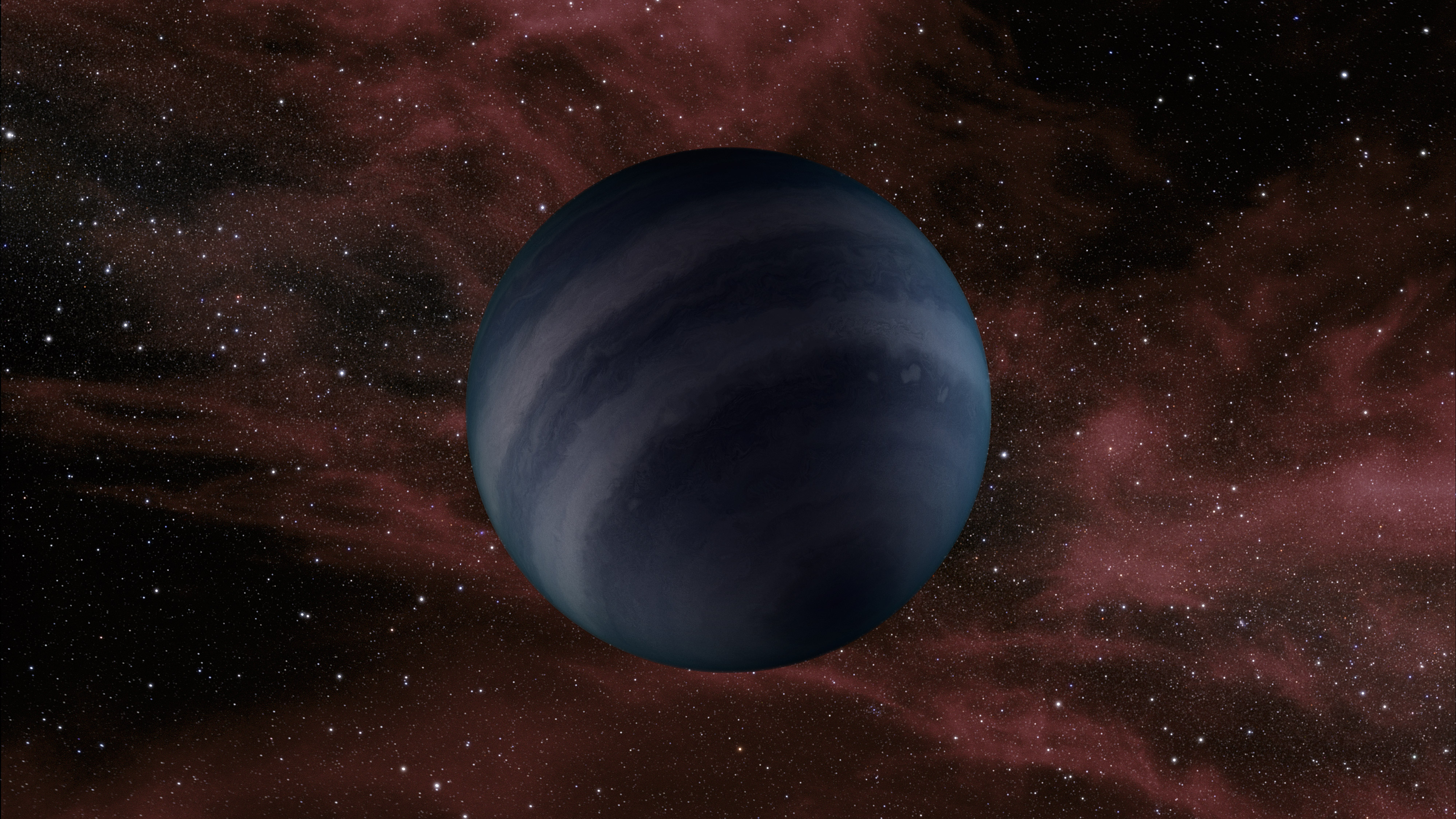

In 2011, astronomers on the hunt for the coldest star-like celestial bodies discovered a new class of such objects using NASA’s Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) space telescope. But until now, no one knew exactly how cool the bodies’ surfaces really are. In fact, some evidence suggested they could be at room temperature.

A new study using data from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope shows that while these so-called brown dwarfs are indeed the coldest known free-floating celestial bodies, they are warmer than previously thought, with surface temperatures ranging from about 250 to 350 degrees Fahrenheit (125 to 175 degrees Celsius). By comparison, the sun has a surface temperature of about 10,340 degrees Fahrenheit (5,730 degrees Celsius).

To reach these surface temperatures after cooling for billions of years, these objects would have to have masses of only five to 20 times that of Jupiter. Unlike the sun, the only source of energy for these coldest of brown dwarfs is from their gravitational contraction, which depends directly on their mass. The sun is powered by the conversion of hydrogen to helium; these brown dwarfs are not hot enough for this type of “nuclear burning” to occur.

The findings help researchers understand how planets and stars form.

“If one of these objects were found orbiting a star, there is a good chance that it would be called a planet,” said Trent Dupuy, a Hubble Fellow at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and a co-author of the study, appearing online in the journal Science Express. But because they probably formed on their own and not in a planet-forming disk orbiting a more massive star, astronomers still call these objects brown dwarfs even if their mass is of planetary size.

Characterizing these cold brown dwarfs is challenging because they emit most of their light at infrared wavelengths and are very faint due to their small size and low temperature.

To get accurate temperatures, astronomers need to know the distances to these objects. “We wanted to find out if they were colder, fainter and nearby, or if they were warmer, brighter and more distant,” explains Dupuy.

Using Spitzer, the team determined that the brown dwarfs in question are located at distances 20 to 50 light-years away.

If one of these objects were found orbiting a star, there is a good chance that it would be called a planet.

To determine the distances to these objects, the team measured their parallax — the apparent change in position against background stars over time. As Spitzer orbits the sun, its perspective changes and nearby objects appear to shift back and forth slightly. The same effect occurs if you hold up a finger in front of your face and close one eye and then the other. The position of your finger seems to shift when viewed against the distant background.

But even for these relatively nearby brown dwarfs, the parallax motion is small. “To be able to determine accurate distances, our measurements had to be the same precision as knowing the position of a firefly to within 1 inch from 200 miles away,” explained Adam Kraus, professor at the University of Texas at Austin and the study’s other co-author.

The new data also present new puzzles to astronomers who study cool, planet-like atmospheres. Unlike warmer brown dwarfs and stars, the observable properties of these objects don’t seem to correlate as strongly with temperature. This suggests increased roles for other factors, such as convective mixing, in driving the chemistry at the surface.

For more information about Spitzer, visit http://spitzer.caltech.edu and www.nasa.gov/spitzer.