Perihelion: 2024 April 21.00, q = 0.781 AU

For this week’s “Comet of the Week” I am turning my eye towards the near-term future: a comet that I hope to see within the next few years.

While there perhaps is no exact formal definition of the term, the phrase “Halley-type comet” is generally used for those comets with orbital periods between 20 and 200 years. (“Centaur” comets like 95P/Chiron and 174P/Echeclus are generally excluded from this; these objects, along with other centaurs, are discussed in a previous “Special Topics” discussion.) Unlike the shorter-period Jupiter-family comets, which tend to have small orbital inclinations, Halley-type comets have inclinations that range all over, and a significant fraction of them are in retrograde orbits. The prototype, certainly, is none other than Comet 1P/Halley itself, with an orbital period of 76 years and which travels in a retrograde orbit with an inclination of 162 degrees.

With the advent of the comprehensive survey programs two decades ago numerous Halley-type comets are being discovered quite frequently nowadays. Prior to that, only a relatively small number of them were known, and there are only a handful of what can be called “classical” Halley-type comets, which perhaps can be loosely defined as those that were known before the beginning of the 20th Century. Some of these comets, like Halley, are moderately bright.

One of these “classical” Halley-type comets was discovered in July 1812 by the champion French comet hunter Jean Louis Pons. The comet reached a peak brightness of approximately 4th magnitude and was followed for two months, which was long enough for the astronomers of that era to determine that it had an orbital period in the vicinity of 70 years. It was expected to return in the early 1880s but was not found despite several searches, but then in September 1883 the champion American comet hunter William R. Brooks discovered a comet which soon proved to be the long-awaited comet discovered by Pons. The viewing geometry was rather favorable during that return, with perihelion occurring in late January 1884; the comet passed 0.64 AU from Earth earlier that month and reached a peak brightness of 3rd magnitude. According to the astronomers of that time, the comet underwent a series of short-lived brightness flares as it approached perihelion, and spectroscopic studies indicated that these were apparently due to ejections of large dust clouds from the nucleus.

German amateur astronomer Maik Meyer has recently completed an examination of historical records in an effort to identify potential earlier returns of Comet Pons-Brooks. A comet observed in January 1457 by Paolo Toscanelli in Florence, Italy, and also by observers in China and Japan, appears to be such a return, as does a comet also observed from China and Japan in October and November 1385. Calculations suggest the viewing geometry would have been relatively favorable during both of these returns, and the available data (such as it is) suggests that the comet was as bright as 2nd or 3rd magnitude both times.

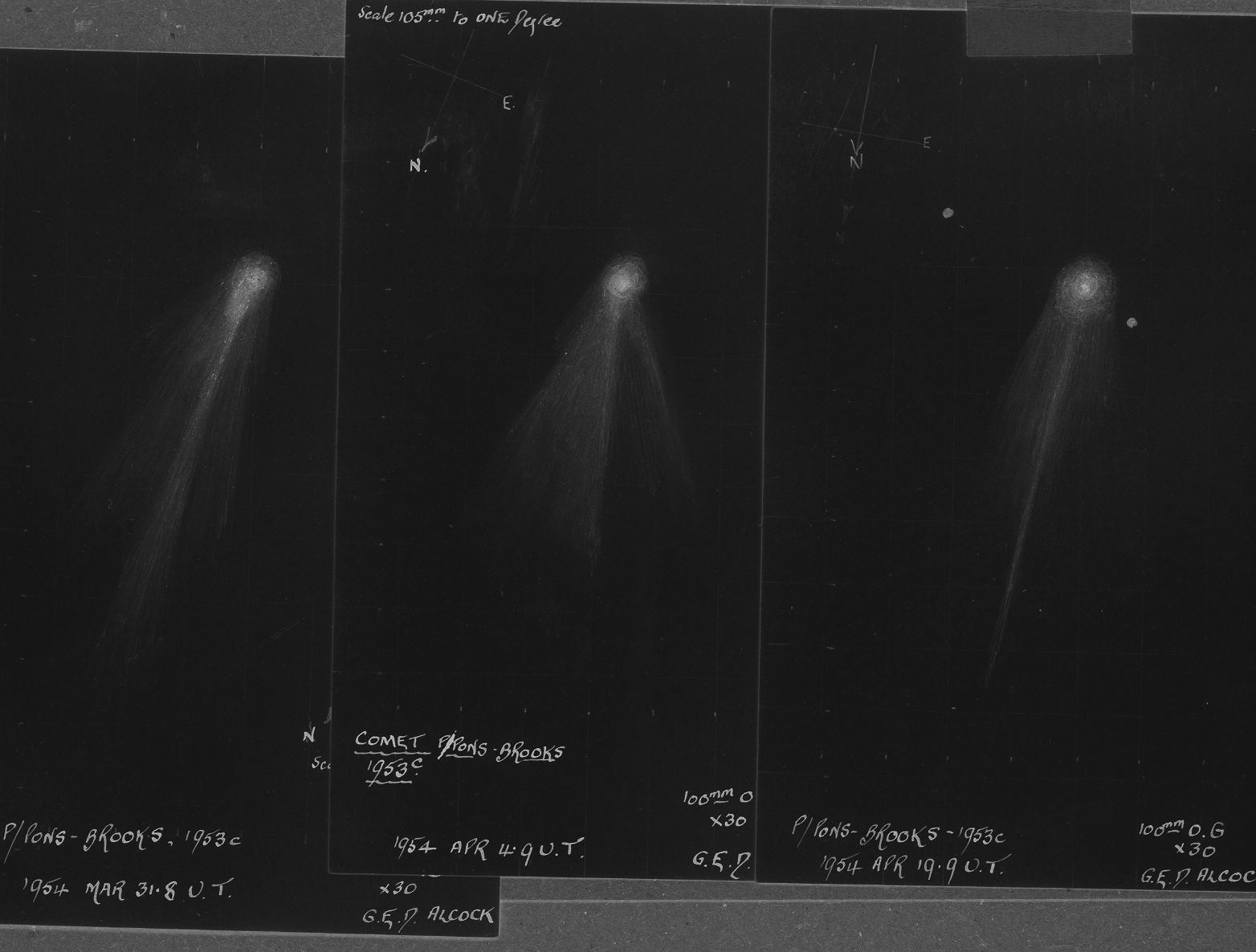

Meanwhile, Comet Pons-Brooks most recently passed through perihelion in May 1954 – four years before I was born, incidentally. The viewing geometry was not too favorable that time and the comet was never brighter than 6th magnitude, although as was the case in 1883-84 it exhibited several short-lived brightness flares while en route to perihelion.

We are now just four years away from Pons-Brooks’ next perihelion passage. As of this writing, it has not been recovered yet, although conceivably that could happen within the not-too-distant future. It is currently located in southeastern Hercules at a heliocentric distance of 12.3 AU, and for the next few years it passes through opposition right around the time of the June solstice.

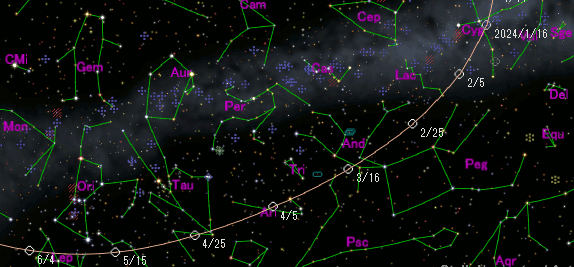

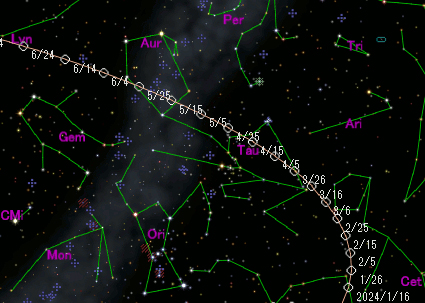

As was the case in 1954, the viewing geometry in 2024 is relatively unfavorable. During the run up to perihelion the comet remains on the far side of the sun from Earth, although it will be located well to the north of the sun and thus observable from the northern hemisphere in the evening sky. On the final approach to perihelion the elongation remains rather small, being around 37 degrees in mid-March and shrinking to 29 degrees by the beginning of April and to 21 degrees by the time of perihelion passage. Since the comet is, intrinsically, rather bright, it may reach a peak brightness of around 5th magnitude. After perihelion it travels southward and will be visible from the southern hemisphere – albeit still at a relatively small elongation for a while – as it recedes and fades.

Comet Pons-Brooks will bring a special treat along with it when it returns. One of the other “classical” Halley-type comets is 13P/Olbers, which was discovered by the German astronomer Heinrich Olbers in March 1815 and which returned in 1887 when it was first picked up by none other than William R. Brooks. It most recently returned in 1956 – just two years before I was born – and reached a peak brightness between 6th and 7th magnitude.

Comet Olbers is next expected to pass through perihelion on June 30, 2024, just a little over two months after Pons-Brooks. As with the other comet, the viewing geometry for Comet Olbers is not especially unfavorable as it stays on the far side of the sun from Earth, with the elongation remaining between 25 and 30 degrees during the final approach to perihelion, but it will remain accessible from the northern hemisphere during this period and should reach a peak brightness between 6th and 7th magnitude. Both comets will be visible in the northern hemisphere’s evening sky during the first few months of 2024, and in mid-April they will pass less than 17 degrees from each other, with Pons-Brooks being perhaps three magnitudes brighter than Olbers but lower in the sky.

More from Week 15:

This Week in History Special Topic Free PDF Download Glossary

Ice and Stone 2020 Home Page