Throughout “Ice and Stone 2020” I refer to numerous specific objects, including in all of my “Comet of the Week” presentations as well as in several of my “Special Topics” presentations and in the lists of weekly historical events. It is appropriate, then, to discuss how these various objects are designated and named.

The conventions used for designating asteroids have changed somewhat over the decades, but, in general, most newly-discovered asteroids are assigned designations of the form:

<year>space<upper case letter><upper case letter><numerical subscript>

Examples would be 2020 AB and 2020 DC5.

In this scheme, the year refers to the year of discovery. The first letter corresponds to the half-month that the discovery took place: “A” is the first half of January, “B” is the second half of January, “C” is the first half of February, and so on. For traditional reasons, the letter “I” is skipped; thus, “H” refers to the second half of April, “J” refers to the first half of May, “K” refers to the second half of May, and so on, up through “Y,” which represents the second half of December.

The second letter of this designation scheme refers to the order of discovery within the half-month in question: “A” is the first asteroid discovered within that half-month, “B” the second asteroid discovered, and so on. Once again, the letter “I” is skipped; thus, the eighth asteroid discovered within a half-month would be “H,” the ninth would be “J,” the tenth would be “K,” and so on, up through “Z,” which would be the 25th. At this point, the letters rewind with a numerical subscript: the 26th asteroid discovered within a half-month would be “A1,” the 27th would be “B1,” the 50th would be “Z1,” the 51st would be “A2,” the 75th would be “Z2,” the 76th would be “A3,” and so on, for as far as necessary. With the advent of the comprehensive survey programs that became operational during the last couple of years of the 20th Century there have been some half-months that have needed three-digit numerical subscripts.

In the above examples, 2020 AB would be the second asteroid discovered during the first half of January 2020, and 2020 DC5 would be the 132nd asteroid discovered during the second half of February 2020.

One significant departure from this scheme involves a series of collaborative programs between Palomar Observatory in California and Leiden Observatory in The Netherlands. In these programs series of photographs taken by Tom Gehrels with the 1.2-m Schmidt telescope at Palomar were carefully scrutinized by the husband-and-wife team of Cornelius and Ingrid van Houten at Leiden in searches for asteroids. The initial “Palomar-Leiden survey” was conducted in 1960, and any asteroids discovered via this survey received designations of the form <four digit number>space”P-L.” This survey was subsequently followed by three additional surveys in 1971, 1973, and 1977 that were designed to search specifically for Jupiter Trojan asteroids (which are discussed in a future “Special Topics” presentation). The asteroids discovered in these surveys were assigned designations in the form of <four digit number>space“T–” <survey> with <survey> being “1,” “2,” or “3” for the 1971, 1973, and 1977 surveys, respectively.

Examples of asteroids discovered during the course of these programs are 3540 P-L, 1180 T-1, 2255 T-2, and 3105 T-3.

Not every asteroid that is discovered and designated is a separate object from all others. Especially with main-belt asteroids, an object may be “discovered” and assigned new designations at various different oppositions. The IAU’s Minor Planet Center is generally tasked, among other things, with finding various linkages between different designations and determining when they might refer to the same asteroid at different oppositions (or sometimes even the same opposition, but found by different surveys). Once such a link is established, an asteroid may then be recovered at future oppositions, and/or found in images taken at previous oppositions.

For example, several years ago the Minor Planet Center found that the asteroids that had been designated 1968 HD, 1976 SO1, 1979 FX1, 1982 SZ4, 1985 HV1, and 1985 JX were in fact all the same object, orbiting in the main asteroid belt with an orbital period of 5.6 years and an eccentricity of 0.14.

These designations are generally considered as temporary. During the first several decades that asteroids were being discovered they were assigned permanent numbers, usually written in parentheses, in the order of discovery. For example, the first asteroid discovered, Ceres, is (1), Pallas, the second asteroid to be discovered, is (2), Eros, the first known near-Earth asteroid, is (433), and so on. Some of these early-numbered asteroids were “lost” after discovery, although all of these have since recovered. (The longest period of being “lost” was for the near-Earth asteroid (719) Albert, which was discovered in 1911 and subsequently “lost” until it was accidentally re-discovered in 2000.)

Today, these permanent numbers are not assigned until an asteroid has been observed at several oppositions and its orbit is well-enough known such that there is no significant possibility that it might become “lost” within the foreseeable future. The multiple-designated asteroid in the above example has now been assigned the permanent number (4151). With the advent of the comprehensive survey programs during the past two decades the number of asteroids with well-determined orbits, and thus with permanent numbers, has skyrocketed; the highest assigned number at this writing is (545135). The vast majority of the higher-numbered asteroids are tiny and dim objects.

Once an asteroid has been numbered, it can be assigned a name. Per tradition, the person or entity that discovers an asteroid has the privilege of proposing a name, which must be approved by a special committee set up by the IAU for this purpose. According to current guidelines, this privilege remains for ten years once an asteroid has been assigned a number; after this time, anyone can propose a name.

Especially with all the surveys going on nowadays, the “discoverer” of an asteroid is not especially clear-cut, and the large majority of discoveries are made by survey programs – many of which operate at least semi-autonomously – and not by individual people. The exact definition of “discoverer” has changed a bit over the years, but today the operational definition is the entity that makes the “earliest-reported observations at the opposition with the earliest-reported second-night observation.”

In continuing with the tradition of the names given to planets, the first asteroids were given names of gods or other entities from Greek or Roman mythology. However, after a while it became apparent that there are far more asteroids than there are gods, and astronomers accordingly began naming asteroids after family members, colleagues, benefactors, observatories, hometowns, and so on.

While most proposed names are acceptable, and are published within the Minor Planet Center’s Minor Planet Circulars on a regular basis, there are some guidelines:

- A name must be 16 characters or fewer in length;

- Pronounceable (in some language);

- Non-offensive.

Names or a purely or primarily commercial nature are not accepted, and names of persons or events known primarily for military or political activities are acceptable only after 100 years or more have elapsed since the person died and/or the event occurred.

Notwithstanding the general acceptance of names, there are certain types of asteroids where certain naming conventions hold. Apollo-type asteroids (i.e., those with perihelion distances within Earth’s orbit) are still generally assigned names out of Greek or Roman mythology, and Aten-type asteroids (i.e., those with orbital periods of less than one year) are generally assigned names out of Egyptian mythology. Jupiter Trojans are assigned names of characters from the Trojan War, with asteroids in the leading group of Trojans (at the Jupiter-Sun L4 point) being named for Greek characters, and asteroids in the following group (at the Jupiter-Sun L5 point) being named for Trojan characters. (Two of the earliest-known Trojans, (617) Patroclus and (624) Hektor, were named before this convention was established, and are thus in the opposite “camps;” they perhaps can be considered as “spies.”) Objects in the Kuiper Belt generally receive the names of creation deities.

Some of the many asteroid names can be considered humorous or otherwise “interesting.” For example, there is (2309) Mr. Spock, named by the discoverer for his cat and not the Star Trek character. (The usage of pets’ names for asteroids is now discouraged). There are also (3142) Kilopi and (11111) Repunit; the rationale for these names is left as an exercise for the reader.

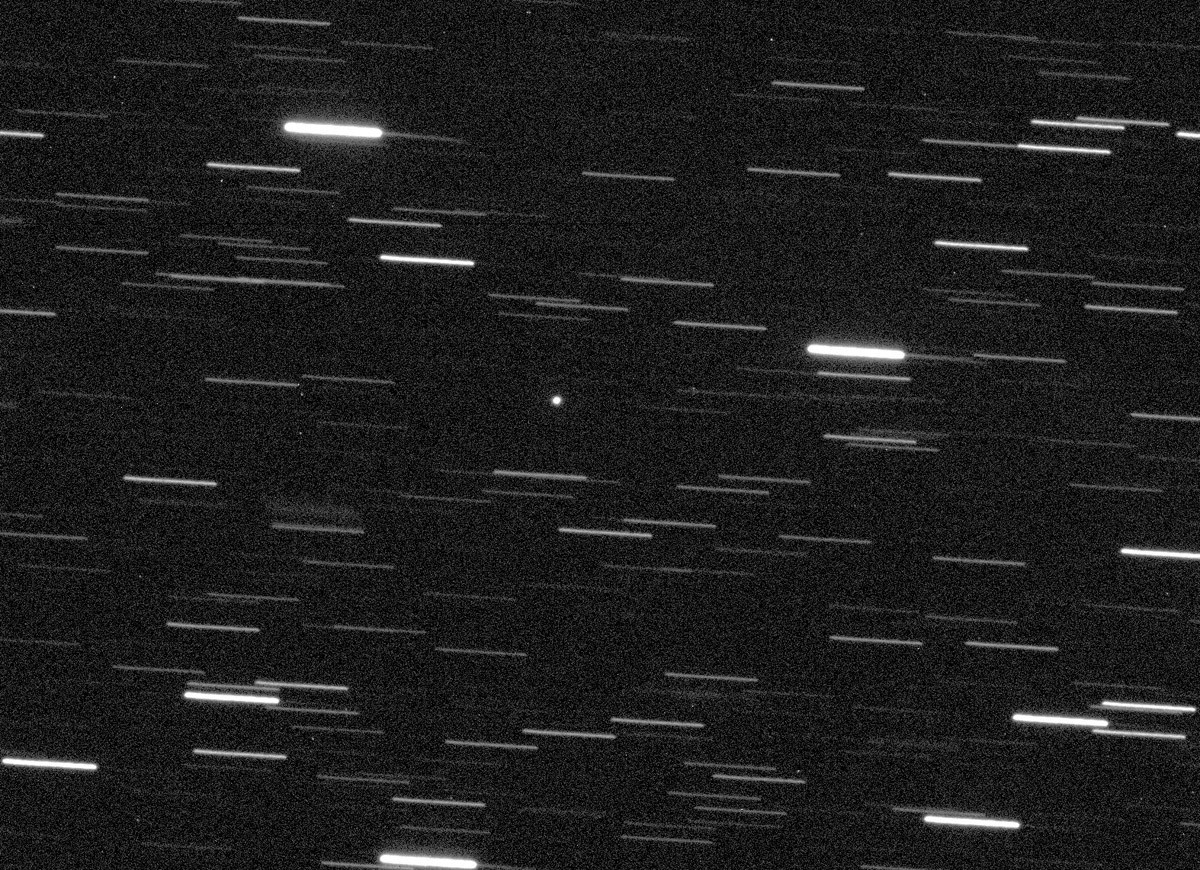

Asteroid (4151), described above, was discovered by the husband-and-wife team of Eugene and Carolyn Shoemaker at Palomar on April 24, 1985, with the primary discovery designation being 1985 HV1. In April 1991 it was given the name Alanhale, the first celestial object, of two, that has my name on it. The second one, which came along four years later, is much better known.

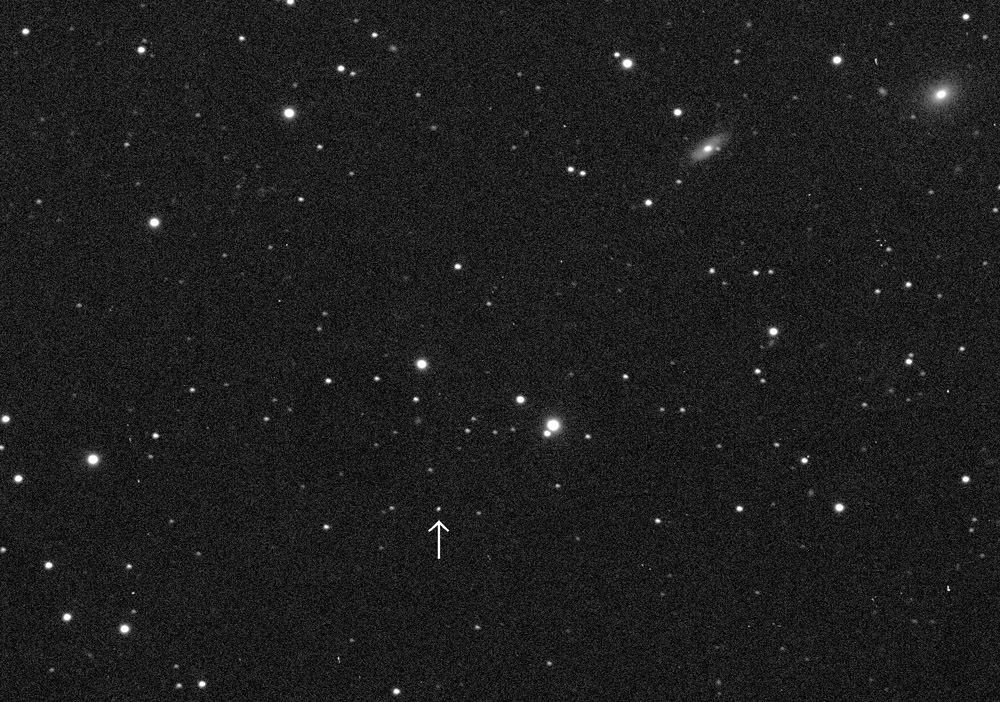

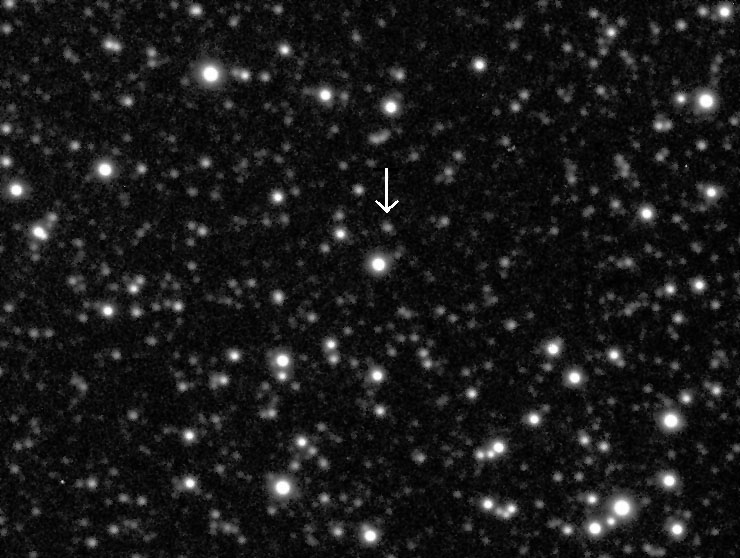

For what it’s worth, (4151) Alanhale will be at opposition this coming August, when it should be around 17th magnitude. It should be a little over a magnitude brighter at the opposition at the beginning of 2023, when it will be close to perihelion.

<year><lower case letter>

In this scheme the “year” would be the year of its discovery, and the lower case letter would indicate the order of discovery that year. (In this scheme, recoveries of expected returns of periodic comets were treated as “discoveries.”) The first comet I ever observed, Comet Tago-Sato-Kosaka, had the designation 1969g, indicating that it was the seventh comet to be discovered or recovered in 1969.

This scheme has an obvious limitation in that it can only accommodate 26 discoveries. Up until the latter decades of the 20th Century this wasn’t an issue, for there weren’t that many comets being discovered. However, as observing techniques and instrumentation improved, and more and more comets began being discovered, it eventually became necessary to expand this scheme, into the following format:

<year><lower case letter><numerical subscript>

In 1987, the first year that this scheme became necessary, the 26th comet was 1987z, the 27th was 1987a1, the 28th was 1987b1, and so on. Although this never became necessary, if there had been a 52nd comet, that would have been 1987z1, the 53rd would have been 1987a2, the 54th would have been 1987b2, and so on.

A couple of years after a particular given year, comets would be assigned “permanent” designations of the form:

<year>space<Roman numeral>

Here, the “year” is the year of perihelion passage, and the Roman numeral indicates the order of perihelion passage during that year. (The one- to two-year delay was meant to allow for any late discoveries that might take place.) Comet Tago-Sato-Kosaka’s permanent designation is 1969 IX, indicating that it was the ninth comet to pass through perihelion in 1969.

As time went by, this dual-designation system became more and more cumbersome, plus there were occasions when very belated discoveries on old photographs required the assignment of permanent designations that were out of order when it came to the sequence of perihelion passages. At the beginning of 1995 the IAU implemented a new scheme, which did away with the perihelion-based designations altogether and instead utilized discovery designations of the form:

<prefix>/<year>space<upper case letter><number>

Here, “year” is the year of a comet’s discovery, the upper case letter refers to the half-month of discovery in the same manner as in the discovery designations of asteroids, and the number is the numerical order of discovery within that half-month.

The prefix refers to the orbital and/or physical status of the comet. The two most commonly-utilized prefixes are “C,” denoting long-period comets, and “P,” denoting short-period comets. (Additional prefixes are discussed below.) The dividing line between “C” and “P” is somewhat arbitrary and has changed a bit over the usage of this scheme, but in general the current dividing line is an orbital period of 30 years.

The formal designation of the comet that bears my name is C/1995 O1, indicating that it was the first comet discovered during the second half of July 1995, and that it is a long-period comet.

It sometimes happens that an object will appear asteroidal at the time of its discovery and will accordingly be assigned an asteroidal discovery designation, however later observations may show that it is in fact a comet. In such cases, the asteroidal designation is maintained, but the appropriate “C” or “P” prefix will be placed in front of it to indicate that it is a comet. Examples are C/1997 BA6 and P/2001 MD7.

Since there is always a bit of uncertainty when it comes to the first expected return of a newly-discovered periodic comet, the first expected recovery will usually be assigned a designation in this scheme. Once that happens, the comet’s orbit can usually be considered as being well-known, and future “routine” recoveries do not receive a designation.

Once a periodic comet is considered “safe” and future recoveries can be considered “routine,” it will be assigned a sequential periodic comet designation of the form:

<number>”P/”<name>

When this scheme was implemented at the beginning of 1995 the “routine” periodic comets already known at that time were assigned the sequential numbers in the order they would have been assigned if the scheme had been in place at the time of their respective discoveries. Comet Halley, for example, is 1P/Halley (which can be shortened to 1P), Comet Encke is 2P/Encke (and shortened to 2P), and so on. At the time of the scheme’s implementation there were 115 numbered periodic comets, but due to the rapid increase of comet discoveries since then, the highest-numbered comet at this writing is 393P.

Other prefixes can be assigned in the discovery designations, as necessary and appropriate:

D: This means that the comet has disappeared. It is usually used when a periodic comet has been missed at several returns, and thus may well have disintegrated, and at the very least is “lost.” It can also mean that a comet has been destroyed, for example, Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9, which impacted Jupiter in 1994, is D/1993 F2. The “D” designation can also be utilized in place of “P” in the list of numbered short-period comets; one of the previous “Comet of the Week” comets is 3D/Biela, which was observed during six returns in the late 18th and early 19th Centuries but which has not been seen since 1852, and which has apparently completely disintegrated.

X: This means that the comet was so poorly observed that no reliable orbit can be calculated. For historical comets this designation is applied to comets that may well have been very bright but there simply isn’t enough accurate positional information that will allow the calculation of a valid orbit, whereas for more recent comets this may be applied to comets that appear on one or two old photographs or images, which is not enough information to allow for the determination of a valid orbit. One future “Comet of the Week” is an “X/”comet.

A: Originally this was meant to be assigned to objects that might have (mistakenly) been described as comets at the time of their discovery and assigned a cometary discovery designation, but later observations show are in fact asteroids. This prefix was never utilized in that sense, but more recently it has been applied to objects that are traveling in definite long-period cometary orbits but that have not exhibited cometary activity. If such an object later does show cometary activity, the prefix can be changed to “C.”

I: This prefix has just recently been added to the designation scheme, and applies to objects – cometary or otherwise – that are interstellar, i.e., they have arrived from outside the solar system on a hyperbolic orbit and will likewise leave the solar system. At this time, two such objects have been found, both of which will be individually discussed in future “Ice and Stone 2020” presentations.

S: This prefixed is utilized to designate newly-discovered moons around planets and asteroids, and is described below.

When the new designation scheme was implemented at the beginning of 1995, all the comets that had appeared prior to that time were retroactively assigned the appropriate “new style” designations. Since the literature references at the time of their respective appearances utilized “old style” designations, and since many of my earlier-observed comets did so as well, for my purposes here in “Ice and Stone 2020” I am using “old style” discovery designations for the pre-1995 comets.

Since about the mid-18th Century comets have traditionally been named for their respective discoverers; this is a tradition from which I have benefited. There have been many occasions when a comet has been discovered almost simultaneously by more than one person, and accordingly has received both names; since Thomas Bopp in Arizona discovered the same comet I did at right about the same time, it accordingly received both our names. Sometimes there are three independent discoverers, and a comet accordingly has received all three names, but for obvious reasons the number of different names given to a comet has been limited to three. Since there have been occasions when a bright comet has suddenly appeared seemingly from out of nowhere and there are many independent discoveries of it, these comets have not necessarily received names but are simply known as the “Great Comet of” whatever year they appeared.

There have also been comets that have been jointly discovered by a team of two or more people. For quite some time the practice has been to give the comet the names of the different people involved in the discovery (again, up to three names), but with the advent of the comprehensive survey programs at the end of the 20th Century it has become the practice to name the comet after the program itself, for example, LINEAR, PANSTARRS, etc. (The various survey programs are discussed in a future “Special Topics” presentation.) Likewise, if a comet is discovered in images taken by a spacecraft, the comet will receive the name of that spacecraft; examples are IRAS and SOHO.

Prior to 1995 a comet would generally be assigned a name when its discovery was announced, but since then the names are assigned later by a committee chartered by the IAU for this task. Among other things, this allows for any belated discovery claims to be analyzed. While each situation may have its own peculiar details, in general, if the person “on duty” for a survey program clearly recognizes a comet as such, it will receive that person’s name, otherwise, it will receive the program name. There has also been a conscious effort by the IAU to limit the names on a comet to two, although sometimes circumstances necessitate a third name; for example, in November 2018 amateur astronomer Don Machholz in California visually discovered a comet, which a few hours later was independently discovered by two Japanese amateur astronomers, Shigehisa Fujikawa and Masayuki Iwamoto, who were utilizing CCDs; the comet – which was formally designated C/2018 V1 – was named Machholz–Fujikawa-Iwamoto.

Sometimes a periodic comet is discovered, then “lost,” and then re-discovered again at a future return. Until 1995, when a comet would receive its name upon discovery, this would usually necessitate the comet’s receiving both names once the identity was determined. Since then, the IAU committee will usually not assign a name until checks for possible identities with previous returns have been performed; if such a check turns up positive, the practice has been not to assign the comet the name of the discoverer on the recent return but rather to keep only the name of the discoverer from the earlier return.

It is not unusual for a discoverer – either individual or team – to discover two or more periodic comets. Prior to 1995, such comets would be assigned sequential numbers to differentiate between them at future returns; for example, Comet Wild 1, Comet Wild 2, etc., Comet Shoemaker-Levy 1, Comet Shoemaker-Levy 2, etc. (Again, these were only assigned to the periodic comets, not to any long-period comets that the discoverer(s) might have found.) With the new scheme implemented in 1995 and the sequential numbers assigned to all periodic comets, this practice was no longer necessary to differentiate between periodic comets, and thus it has been discontinued. In fact, it has been argued that the periodic comet numbers alone can serve as sufficient for identification, and officially the earlier-assigned numbers are no longer utilized; for example, Comet Wild 1 is now officially 63P/Wild (and not 63P/Wild 1), Comet Wild 2 is now officially 81P/Wild and not 81P/Wild 2, and so on. For my purposes here in “Ice and Stone 2020” I am keeping the earlier-assigned numerals; the Week 1 “Comet of the Week” can be called either 81P/Wild or 81P/Wild 2; I called it the latter, although formally it is referred to as the former.

Especially with the advent of the comprehensive surveys, in which more and more comets are being discovered by and assigned the names of those surveys, the IAU has wished to de-emphasize the importance of the names. (With even more comprehensive surveys expected to become operational within the not-too-distant future, the rationale for this should continue to become more apparent.) The formal practice of the IAU is to make the discovery designation of a comet the primary means of identifying it, with its name being added parenthetically; for example, the comet that bears my name is known officially as:

Comet C/1995 O1 (Hale-Bopp)

For my purposes here in “Ice and Stone 2020” I am elevating the importance of the name to being equal to that of the discovery designation, and am reversing the order, for example:

Comet Hale-Bopp C/1995 O1

While “small bodies of the solar system” usually refers to asteroids and comets, the moons of the planets – and, in particular, the smaller moons that may actually be “captured” asteroids and/or comets – as well as the moons of individual asteroids, are also “small bodies.” They will, in fact, be covered in some detail in a future “Special Topics” presentation.

The current designation scheme for newly-discovered moons was implemented in 1978, although it has undergone some minor modifications since then. At present, the scheme for moons of major planets follows the following format:

S/<year>space<one-letter abbreviation of planet>space<number>

As with asteroids and comets, the “year” is the year of discovery, and the number is the sequential order of discovery (around a particular planet) that year. The one-letter abbreviations are, as one would expect, “J” for Jupiter, “S” for Saturn, “U” for Uranus, and “N” for Neptune. For example, if a moon around Jupiter were to be discovered this year, it would be designated S/2020 J 1, and if two moons were to be discovered around Saturn, the first would be S/2020 S 1 and the second would be S/2020 S 2.

Once a moon has been observed sufficiently well such that its orbit is well-determined and that it will no longer be “lost,” it can be assigned a permanent designation. (Sometimes, as in the case with asteroids, this orbit-determination process may involve objects discovered in earlier years but subsequently “lost.”) This permanent designation has the form:

<Planet>space<Roman numeral>

The Roman numerals are sequential. At this time, Jupiter has 72 moons that have been so numbered, and seven moons that are “lost;” if and when any of those are re-discovered or an as-yet-undiscovered moon is found and observed well enough for a valid orbit determination, it would be designated Jupiter LXXIII. For what it’s worth, at this time Saturn has 53 formally-designated moons (with over 30 more – many of which were just announced late last year – awaiting confirmation or recovery), Uranus has 27, and Neptune has 14.

For the most part, names have been assigned to moons in keeping with their respective parent planet. Jupiter’s moons have usually been named for descendants of the mythological Greek god Zeus, Saturn’s moons have usually been named for the Greek Titans and their descendants, and Neptune’s moons have been assigned the names of Greek water deities. Following the precedent set by William Herschel, who discovered not only Uranus but also its first two known moons (Titania and Oberon), Uranus’ moons are usually assigned names out of the plays of William Shakespeare. With the advent of modern imaging technology which, in theory, can allow for very tiny moons to be discovered, the IAU has been discouraging the assigning of names to more recently-discovered moons, although a few have nevertheless been assigned.

The designations for moons of asteroids follows the same basic scheme, with the exception that an asteroid’s formal sequential number is used instead of the first letter of its name. The first-known asteroid moon to be designated was found (by the Galileo spacecraft) around the main-belt asteroid (243) Ida, and was designated (in the current scheme) as S/1993 (243) 1, and the moon around the near-Earth asteroid (65803) Didymos (the destination of the forthcoming DART mission, which was discussed in the “Special Topics” presentation two weeks ago) was designated S/2003 (65803) 1. Formally, these moons are now designated (243) Ida I and (68503) Didymos I.

Although only a handful of asteroidal moons have been formally named, in general those that have been have followed the precedent established by moons of the major planets, i.e., some association with the name of their parent body. For example, Ida’s moon has been named Dactyl, after the creatures that inhabited the mythological Mount Ida. Didymos’ moon has not received a formal name at this time, although it is informally known as “Didymoon;” perhaps it might receive a formal name by the time DART arrives.

More from Week 17:

This Week in History Comet of the Week Free PDF Download Glossary

Ice and Stone 2020 Home Page