Tales of strange alien worlds, fantastic future technologies and bowls of sentient petunias have long captivated audiences worldwide. But science fiction is more than just fantasy in space; it can educate, inspire and expand our imaginations to conceive of the universe as it might be.

We invited scientists to highlight their favourite science fiction novel or film and tell us what it was that captivated their imagination – and, for some, how it started their career.

Bryan Gaensler, astronomer, University of Toronto

Time for the Stars

– Robert A. Heinlein

Long before the era of hard science fiction, Robert Heinlein took Einstein’s special theory of relativity and turned it into a masterpiece of young adult fiction.

In Time for the Stars, Earth explores the Galaxy via a fleet of “torch ships”, spacecraft that travel at a significant fraction of the speed of light. Communication with the fleet is handled by pairs of telepathic twins, one of whom stays on Earth while the other journeys forth. The supposed simultaneity of telepathy overcomes the massive time delays that would otherwise occur over the immense distances of space.

The catch is that at the tremendous speeds of these torch ships, time travels much slower than back on Earth. The story focuses on Tom, the space traveller, and his twin brother Pat, who remains behind. The years and decades sweep by for Pat, in a journey that takes mere months for Tom. Pat’s telepathic voice accelerates to a shrill accelerated squeal for Tom, as Einstein’s time dilation drives them apart, both metaphorically and physically.

This is ultimately a breezy kids’ adventure novel, but it had a massive influence on me. Modern physics wasn’t abstruse. It was measurable, and it had consequences. I was hooked. And I’ve never let go.

Michael Brown, astronomer, Monash University

2001: A Space Odyssey

– Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey encompasses human evolution, space, alien life and artificial intelligence. Despite being released the year before Apollo 11, the Academy Award winning special effects still make its vision of space inspiring. It can be spine tingling when seen at an old fashioned cinema with a wide screen and a 70mm print (such as Melbourne’s Astor).

2001 is also a product of its time. During the 1960s NASA consumed roughly 4% of the US federal budget, and if that had continued, then perhaps the International Space Station would be a giant rotating behemoth seen in 2001. Indeed 2001’s Pan Am spaceplane seems like a natural progression from early (ambitious) proposals for the Space Shuttle.

Technologies in the film are ahead and behind what we have today.

The most memorable (and arguably emotional) character of 2001 is HAL, an eerily intelligent computer that is far in advance of any computer in existence. And yet astronauts on the moon are using photographic film, rather than digital cameras.

Kubrick deliberately made some space travel seem routine, so his space travellers are frozen in 1960s norms. The astronauts are mostly white men, with women mostly relegated to roles such as flight attendants (an exception is a Soviet scientist). Fortunately, in this regard, the 21st century is more advanced than 2001’s imagined future.

Alice Gorman, space archaeologist, Flinders University

Out of the Silent Planet

– C. S. Lewis

The first book of the classic “Space Trilogy” was written 20 years before the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957, the first “world-circling spaceship”. C. S. Lewis was no scientist – he was a professor of Medieval and Renaissance literature – but his deep knowledge of pre-modern cosmology gives his take on space travel a unique flavour. I find myself returning to Out of the Silent Planet and its sequel, Voyage to Venus, over and over again.

In the story, Lewis’ hero, Ransom, becomes a reluctant astronaut when kidnapped by the uber-colonial “hard” scientist Weston for a journey to Mars. Confined in the spherical spaceship, he becomes aware of a constant faint tinkling noise. In the world before space junk, it is a fine rain of micrometeoroids striking the aluminium shell.

Ransom’s “dismal fancy of the black, cold vacuity, the utter deadness, which was supposed to separate the worlds” fostered by modern science, is transformed by the experience of actually being in space.

His revelation is an intimately joyous recognition that space, far from being dead, is an “empyrean ocean of radiance”, whose “blazing and innumerable offspring” look down upon the Earth. He feels “life pouring into him from it every moment. How indeed should it be otherwise, since out of this ocean all the worlds and all their life had come?”

How, indeed, could we not long for space after such a vision as this?

Duncan Galloway, astrophysicist, Monash University

Ringworld

– Larry Niven

It was Larry Niven’s Ringworld that led, in part, to my career in astrophysics.

Ringworld describes the exploration of an alien megastructure of unknown origin, discovered around a distant star. The artificial world is literally in the shape of a ring, with a radius corresponding to the distance of the Earth to the sun; mountainous walls on each side hold in the atmosphere, and the surface is decorated with a wide variety of alien plants and animals.

The hero gets to the Ringworld via a mildly faster-than-light drive purchased at astronomical cost from an alien trading species, and makes use of teleportation disks and automated medical equipment.

The appeal of high-technology stories like this are obvious: many contemporary problems, like personal transportation, overpopulation, disease, and death have all been solved by advanced technology; while of course, new and interesting problems have arisen.

Grand in scope, and featuring some truly bold ideas, Ringworld (and Niven’s other books set in “Known Space”) are as keen now as when they were written, 40 years ago.

Helen Maynard-Casely, planetary scientist, ANSTO

The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy

– Douglas Adams

Whether you have heard the radio play, read the book or seen the film, this story of a hapless Englishman negotiating his way through the galaxy is an essential piece of nerd culture. I first heard the play as a teenager, and even now not many weeks go by without me delving into sections of this trilogy of five-parts.

As a scientist, my life can seem a little zany to an outsider. When your job does sometimes actually entail reversing the polarity of a neutron flow, you need to look to an even crazier fiction world for your escapism. And for me this book is it. A world where sperm whales and bowls of petunias can appear in space for no reason at all and staggering co-incidences happen every time you power up your spaceship.

The genius (and I do not use that word lightly) of Douglas Adams’ writing is that the loopy concepts of the book are presented with a thin veneer of “scienceness”, enough to make the fantastical concepts that little more believable. Then he “normalises” it all. A packet of peanuts will help you survive a matter transference beam, for instance.

The heart of this book is its characters, a suite of people/aliens that are echoed in every workplace (certainly every laboratory) across the world. Walk into any science institute and there will be a two-headed power-hungry presidential leader railing upon post-docs, with brains the size of planets, who really wish you hadn’t talked to them about life.

I get the impression that Douglas Adams would not have wanted you to take anything away from this book. But, for me it gives continued inspiration that there is always another way to sidle up to a problem. Most of all though: don’t panic.

Matthew Browne, social scientist, CQUniversity

Consider Phlebas

– Iain M. Banks

I love a lot of science fiction, but Iain M. Banks’ classic space-opera Consider Phlebas is a special favourite.

Banks describes the “Culture”, a diverse, anarchic, utopian and galaxy-spanning post-scarcity society. The Culture is a hybrid of enhanced and altered humanoids and artificial intelligences, which range from rather dull to almost godlike in their capabilities.

Most people in the Culture lead a relaxed, hedonistic lifestyle, going to parties, doing art, taking drugs (which they can synthesise from bio-engineered glands) and generally having fun. The tedious business of actually running the whole show is mostly left up to the most powerful AIs, called Minds, who manifest themselves in the great star-ships and orbitals in which most citizens live.

Of course, it’s a big galaxy, and not everyone shares the Culture’s easy-going approach to galactic citizenship. Consider Phlebas is set against the backdrop of a growing conflict between the Culture and the Idiran, a speciesist, religious and hierarchical empire with expansion on its mind.

Perhaps the best thing about Consider Phlebas (apart from the wonderfully irreverent ship names the Minds give themselves) is the fact that a story from this conflict is told from the perspective of an Idiran agent, who despises the Culture and everything it stands for.

My own take on the book is as an ode to progressive technological humanism, and the astute reader will find many parallels to contemporary political and cultural issues.

Rob Brooks, evolutionary biologist, UNSW Australia

The Truman Show

– Peter Weir

Truman Burbank, played with a delectable balance of animation and pathos by Jim Carrey, lives a confected life as unwitting protagonist in a reality television show. Conceived on camera, adopted by a corporation and manipulated at every stage by the show’s sinister creative genius, Christof (Ed Harris), Truman nonetheless comes to realise that his world is a sham and that almost every interaction he ever had was a lie.

Against the backdrop of Seahaven’s dystopic perfection, Weir exposes prescient glimpses of reality television, surveillance culture and the stalkerish targeted advertising we now find in our social media streams.

It’s like a peppy 1984 but with corporate hegemony replacing the totalitarian state. But I was most gripped by the fresh take on ancient debates about rationalist nature and empiricist nurture.

As a student of behaviour, I’ve always rued the amputation of biology from the social sciences, particularly the wasted opportunity that saw sociobiology turned into a perjorative in the late 1970s, at least outside the study of insect sociality. The rejection of evolutionary thinking as “biological determinism”, and its positioning as opposite to progress and liberation, has always rankled me.

I recall watching the film alone, between conferences, at an ancient cinema in Santa Cruz. What excited me most, and kept me up much of the night scribbling notes that would eventually shape my research direction and lead me to popular writing, was Weir’s clever inversion of the relationships between nature/nurture and determinism/free will.

While Cristof’s nurture tramples Truman’s nature throughout the film, in the end something inherent to Truman sets him free, as he whispers: “You never had a camera in my head!”.

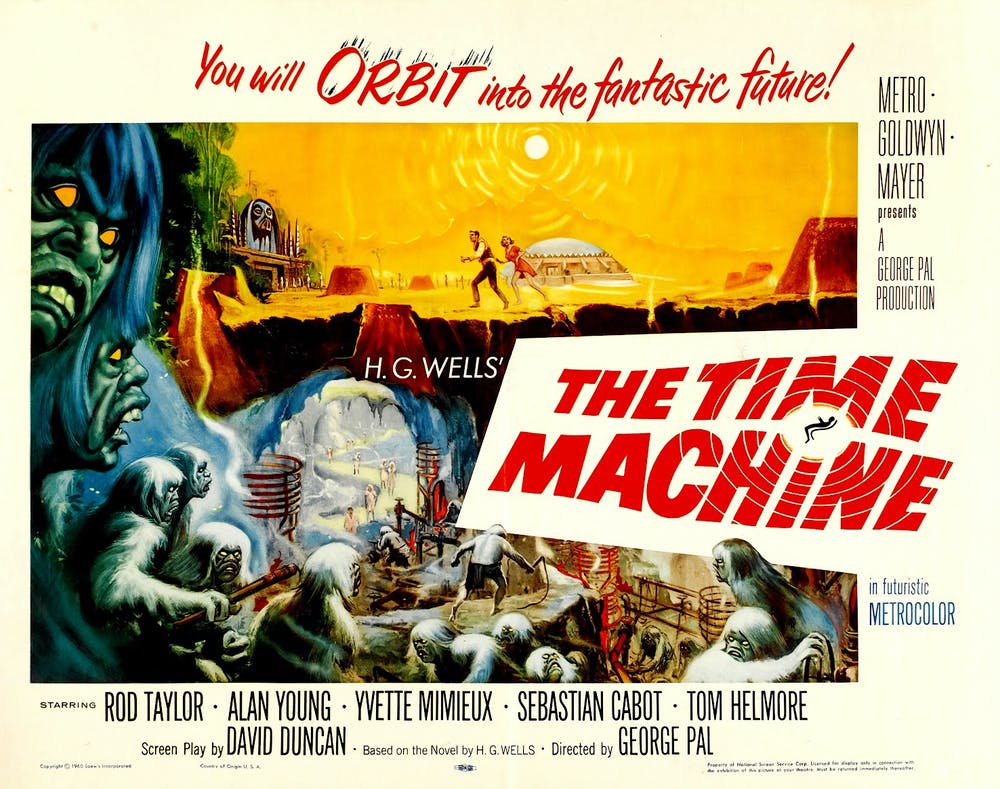

Geraint Lewis, astrophysicist, University of Sydney

The Time Machine

– H. G. Wells

In the decade before Albert Einstein told us that time and space were malleable, H. G. Wells gave us the adventures of the Time Traveller.

We never learn the name of this Victorian scientist, a man who explains “there is no difference between time and any of the three dimensions of space” and builds a machine to explore this new world. It was not from Einstein that I discovered the non-absolute nature of space and time, but from the Time Traveller, and his present-day incarnation, Doctor Who.

The Traveller doesn’t head to past, to be a voyeur at historical events, but into the unknown future. And the future of Wells is not glorious! The Traveller finds evolution has split humans in two, with delicate Eloi being little more than food for the subterranean Morlocks.

Escaping mayhem and heading even further into the future, the Traveller finds the life’s last gasp under a swollen, red sun, eventually seeing the Earth succumbs to final freezing, before he returns to the relative safety of Victorian London.

This scientific vision of the future struck me, and the nature of time has remained in my mind. At the end of the story the Traveller heads back to continue his exploration of the future; playing with the equations of relativity is likely to be the closest I will ever come to realising this dream.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Contributing authors to this article are Michael J. I. Brown, Associate professor, Monash University; Alice Gorman, Senior Lecturer in archaeology and space studies, Flinders University; Bryan Gaensler, Director, Dunlap Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Toronto; Duncan Galloway, PhD; Senior Lecturer in Astrophysics, Monash University; Geraint Lewis, Professor of Astrophysics, University of Sydney; Helen Maynard-Casely, Instrument Scientist, Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation; Matthew Browne, Senior Lecturer in Statistics, CQUniversity Australia, and Rob Brooks, Scientia Professor of Evolutionary Ecology; Director, Evolution & Ecology Research Centre, UNSW.