Have you ever stared up at the night sky contemplating how the universe works? Have your thoughts ever drifted off into the realm of the infinite? Theoretical physicist Brian Greene not only ponders these questions, but his research into String Theory could one day prove successful in answering them.

Greene is an author, professor, creator of his own Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC), and a vegan ice cream lover. He has even made guest appearances on high profile television shows, such as “The Big Bang Theory”. First and foremost, through his research, Greene is searching for answers to some of the deepest questions surrounding the structure and creation of the universe.

The simplicity behind the thoughtful explanations to questions that boggle the greatest minds in science, stood out to me most when interviewing Greene. Because he is extremely talented at generating descriptive and vibrant explanations, it felt like he was splashing color on a canvas in my mind. He carefully approached every question without judgment – from the far-out and theoretical, to the concrete and factual.

At the beginning of our interview, I furiously took notes, but as we progressed, I let the recorders do the work and just listened to the stream of thought he shared with me on some of the most beautiful and elusive mysteries surrounding the cosmos.

RocketSTEM: Why physics? Were you curious as a child? Did that curiosity guide you gracefully towards your career path?

Brian GREENE: “It was a pretty seamless path. When I was a little kid I was completely fascinated by numbers, so I was kind of a math kid. A little later on I learned that math was more than just something you played with – that it could be used to describe how the world works – and that was a pivotal moment for me. I carried on that trajectory of applying mathematics to understand the physical universe, then as a grad student using math for some of the more esoteric and far-out ideas of physics. Things like unified theories and string theory I worked on and continue to work on, and that pretty much landed me where I am now.”

RS: What was a challenge you overcame to get where you are, something that people can relate to?

GREENE: “Well, physics is challenging every minute of every day. I like to think of it the following way: we have certain mental abilities that were largely formed in response to our need to survive. When we were in the jungle learning survival skills, really understanding how the world works and the mathematics of the underlying reality wasn’t useful. What was useful was the ability to run fast enough to catch your dinner.

What we do in physics is, in some way, going against the grain of evolution. We are really trying to push our minds into a place that they weren’t necessarily meant to go. That’s not easy. It’s not easy for students to learn physics and it’s not easy for physicists to do physics, but the ideas are so exciting, so wondrous, that we’re compelled to push onward, and push through those challenges. So I encourage all students to push through those challenges and recognize that they aren’t alone – even professionals are constantly scratching their heads, working hard to try to make progress.”

RS: What is a really cool fact about you – something that no one would expect?

GREENE: “Well, I don’t know if it’s a ‘cool’ or ‘curious’ fact, but I am vegan. I don’t eat anything of animal origin. When I was nine years old, I was a city kid, so I didn’t know where meat came from; it was just this stuff that came packaged from the supermarket. Then my mother made spare ribs, and that made the connection for me. The fact that it was an animal was obvious all the sudden and that sickened me. So, I stopped eating meat at that age, but I still ate dairy.

Then much later, about 20 years ago, I went to an animal sanctuary in upstate New York, a little town called Watkins Glen, and I learned about the dairy industry and how the animals are so mistreated. I could feel it coming, and a few days later, I just could not eat dairy anymore. I’ve been vegan ever since.”

RS: What is your favorite ice cream? Oh, wait! You don’t eat ice cream – that strikes that question!

GREENE: “Well, that’s not true! So, there are now ice creams that are dairy-free. My favorite one is … um … goodness. Well, it’s my favorite but I can’t remember its name. It’s a coconut vegan ice cream…it has bliss in the name…Coconut Bliss! My favorite flavor is …um…I forgot its name, too. You can ask me about the universe, but my favorite ice cream stumps me.

(He took to Google at this point.)

What is that flavor, that’s not it, that’s not it, negative, negative…OH! Cherry Amaretto, man, that is my favorite.”

RS: Would you want to live forever?

GREENE: “YES! So long as I could have my wife and my kids. And my ice cream, too.”

RS: What was your inspiration for creating World Science U and what kind of student did you have in mind?

GREENE: “The point of World Science University (WSU) is to bring science education to anybody who wants it. And I mean that literally – it really can be for the high school kid who is very advanced and finds school not challenging enough, for the college student who’s having difficulty in the classroom and needs help outside of the traditional instruction at their college.

It’s for the lifelong learner who gave up on science many years ago, but has always wanted to reconnect with it, and didn’t want to go back to college and enroll in classes – but this is a way in which, in his or her own time, one can immerse themselves in many wonderful ideas. The intended audience is broad.”

RS: How do you hope your students will utilize what they have learned in your courses?

GREENE: “Well, the initial courses that WSU is offering are in Einstein’s Special Relativity. That’s a subject which is not something that a student is going to apply to everyday circumstances – it tells us how the world behaves in unusual circumstances – when things are moving very, very quickly.

Rather than thinking about somebody using this material to specifically do something, what I really want is for people to leave the class with a completely changed perspective on how reality works – a very different perspective on the meaning of space, on the meaning of time, on the meaning of math, on the meaning of energy.

It is a course that has a capacity to really shake up one’s perspective on how the universe works.”

RS: Do you plan on eventually morphing this into a degree or certificate program?

GREENE: “We do offer certificates now to people that complete the initial courses. In terms of degrees – who knows? Way down the line I could very well imagine that there might be a more formal way in which a student can get credit for achieving a level of proficiency in these online courses.”

RS: Are you going to teach the courses yourself in the beginning?

GREENE: “Yes, I am the initial instructor, just to get the ball rolling, but we are now in conversation with a number of leading scientists, in a variety of areas, who are slated to be the next people in.”

RS: What are you most looking forward to about the World Science Festival later this month?

GREENE: “It is always full of surprises and great programs. I’m doing a program on quantum mechanics with a number of world renowned folks, whose expertise is in quantum physics. I also know there is a really cool event happening on the Intrepid ship in the Hudson river, and we are doing a screening of a science related film, together with astronauts to interact with families and audiences after the film. We like to think of it as a coming together of science and music and art and theater and film to create a celebration of one of the most important things our species does, which is explore.”

RS: What is your opinion of a “Horton Hears a Who” scenario for the universe? Stepping out of the science, what kind of ideas do you have about ‘what we are’?

GREENE: “The notion that there are worlds within worlds and that the reality we experience in everyday life is one level of reality – whether a very tiny realm or a very big realm, there are vastly different phenomena that take place – that really is true. That is what modern physics has taught us.

It hasn’t taught us that little tiny people live down there, but it has taught us that the laws at work in the microscopic realm are so different from the ones that we experience up here, that it is its own wondrous, distinct, separate universe. And the metaphor, the Dr. Seuss story, I think is aligned well with modern thinking.

Now, consider this. We think of ourselves as intelligent life. We share 99 percent of our DNA with chimps so a little tiny shift in our DNA takes you from chimp to us. Now, that suggests that if there are other creatures in the universe whose DNA differs from ours, for example, by a few percent in the right direction, their intelligence could be so enormous compared to ours, that they would look at us as if we were a bacteria. They would look at us as if we were worms crawling around on the surface of the earth.

So we always ask ourselves if there is other life in the universe. The answer might turn out to be that there is, and that life is so intelligent that when compared to ours, they’re really not interested in us, just like we really aren’t that interested in worms or bacteria, in that sense.”

RS: What do you think is outside of space? How did something come from nothing?

GREENE: “First of all, as for what is outside of space, well there simply may not be an outside of space. It makes sense to talk about what’s outside of your building, or what’s outside of your country, what’s outside of the earth, the galaxy – all that makes sense. But when it comes to the universe, it may be that it truly encompasses everything. And the notion of an “outside of the universe” may simply just be a concept that doesn’t make any sense.“

RS: Back to the big bang…doesn’t something have to exist for something else to come from it, though? How did something just start…from nothing?

GREENE: “Yeah, I mean, that’s again one of those natural thoughts based on everyday experiences. Because in everyday life, every object we experience, look at, has a history. That history involves us being created from other stuff that existed before the object ever existed. And maybe it will be true of the universe, too. Maybe it will be that our big bang, is not the beginning of everything, it was simply an event in a pre-existing reality and there may be a prehistory to the big bang – that’s quite possible.

On the other hand, it may be the case, that the universe is different from a baseball, a painting, or any other objects in the world that all have a prehistory. The universe may have come into existence in a given moment and there may not have been a prehistory there may not have been anything before that event took place.

Or, maybe the laws of physics existed, but somehow there wasn’t a physical reality within which those laws operated until those laws somehow coaxed the big bang into taking place, then all of the sudden there was stuff on which those laws operate. Perhaps before all that stuff was there, it was just the laws itself, some abstract realm.”

RS: How can there be any more than three dimensions, why is time described as a dimension, and do you see it as tangible?

GREENE: “When we talk about dimensions of space, indeed we imagine that there are three of them, (length, width, height) but it could be that there are dimensions in addition to those, that for some reason our eyes don’t directly see or directly detect.

In fact, I spent much of my adult career developing mathematical theories that’ll allow the universe to have a fourth, fifth, sixth dimension and so on in a way that wouldn’t contradict the fact we haven’t seen those dimensions.

Don’t allow your eyes to fool you into thinking that what you see is everything

Now, for time, we think of it as a piece of information necessary to delineate when and where an event takes place. For instance, if you are having a dinner party, you give your guests the street, cross street and floor numbers, to get to your apartment, but you also need to give them a time, so that they know when to show up. In that sense, that’s four pieces of information we consider to delineate where the party is taking place – in four dimensions – three of space and one of time.”

RS: In the absence of empirical data, how do you decide between different hypotheses? Do you have some kind of intuition for what might be true, do you go for the most beautiful theory, or do you go with the one that is most amenable to mathematical analysis?

GREENE: “Well I do think that the ultimate arbiter of truth is experimental data. So that is the thing that clearly trumps everything else. In the absence of that, you do use your intuition, your gut feeling – your aesthetic sense of which ideas seem most promising.

That doesn’t mean those ideas are right, it does, however, mean that you, based on your personal judgment, feel that they are the ones most worthy of your time and attention in order to be further developed. However, it could well be that things which did not feel intuitively correct, or the right way to go, may ultimately be picked out by nature.

Nature doesn’t care so much about our feelings – nature has her own set of rules and it is up to us to try to discern them.”

RS: What is the shape of space and what do you think of dark matter?

GREENE: “For the shape of space, the data seems to suggest that space is very close to being flat – in a sense that it doesn’t’ have any intrinsic curviness to it. Rather than being like the surface of a ball, the shape of space is more like that of a tabletop. And that tabletop might go on forever in all directions – that is our best guess at the moment.

As for dark matter, the evidence seems to be accumulating over many decades that there is matter in the universe that doesn’t give off light, but it does exist. It is exerting the force of gravity, and that is how we know the matter is there – even though we don’t see it – and that sets up a challenge to identify what constitutes dark matter.

People have been looking for the constituents of dark matter for a number of years – surprisingly yet – nothing has been confirmed. We are hoping in the next few years, that issue will be settled.”

RS: In simple terms, can you explain what string theory is?

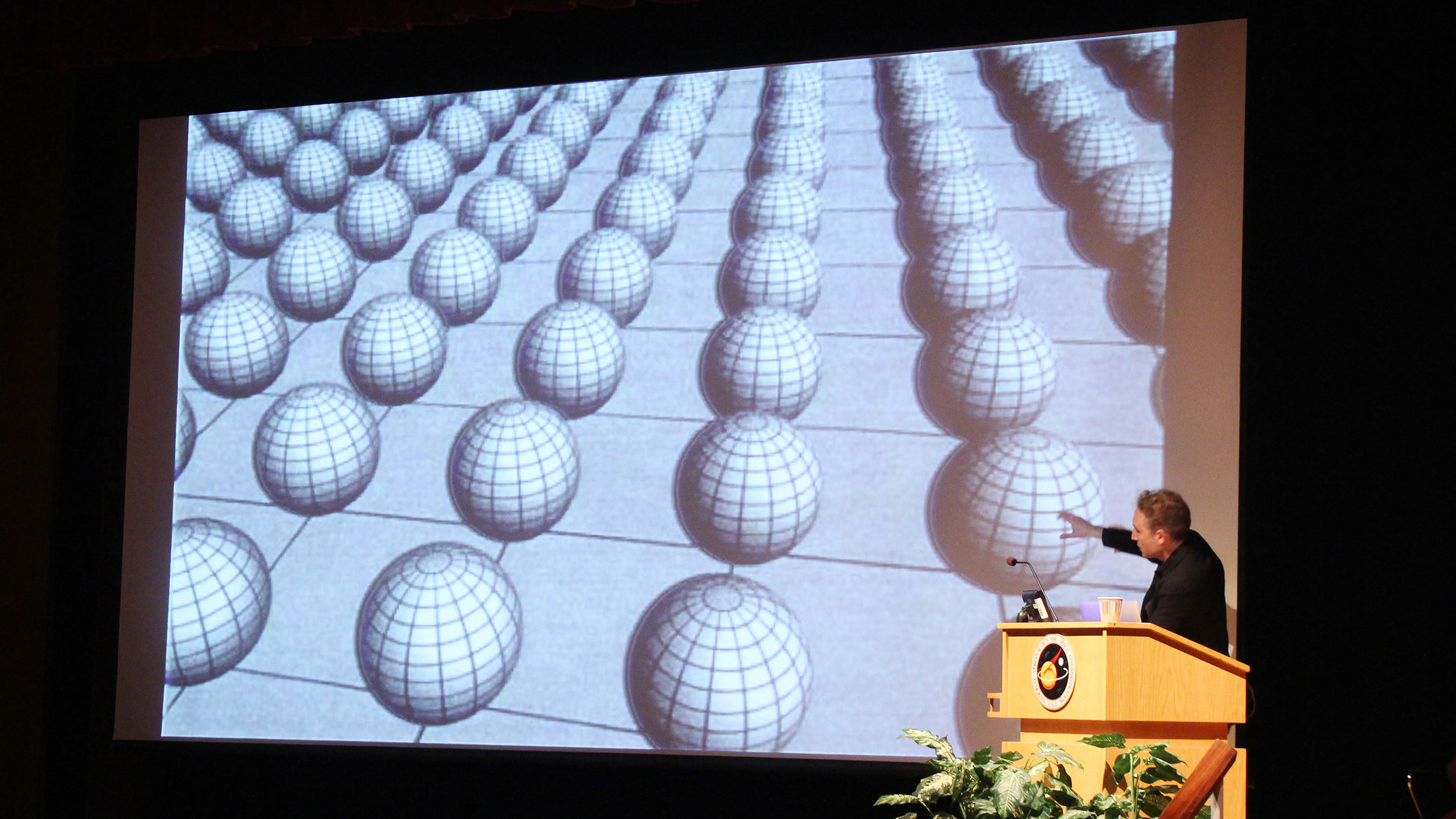

GREENE: “String Theory is a proposal that tries to reach Einstein’s dream of a unified theory of physics. And by that, Einstein meant the theory that from one principle – maybe to be articulated by one mathematical equation – we might describe everything. This includes stars and galaxies (the big stuff), the small stuff, molecules and atoms, and everything in between.

The way String Theory works, is to imagine that matter is not what we thought it was. Rather than matter being little dot like particles with no internal machinery, String Theory envisions that the constituents are little stringy filaments, and their different vibration patterns are meant to describe everything that happens in the world.

It is a hypothetical theory, and we are still trying to develop it in order to test it – it hasn’t yet been tested.”

RS: What do you think of the discovery of the gravitational waves that prove the big bang happened?

GREENE: “It is extremely exciting! If the results stand, they will be among the most important findings in cosmology and the search for the origin of the universe. It will be one of the most important findings in a hundred years. They will give us a new observational window into the earliest moments of creation, which will be a very powerful, new tool for us to use to understand the universe. However, I also want to emphasize that we won’t really believe these results until they are independently confirmed by other groups of researchers. But the team did a great job!”

RS: How are we trying to measure some of the alternate energies (i.e. dark energy)?

GREENE: “Well, measuring dark energy is a challenge, but there are very good teams of astronomers that have worked out techniques that often have to do with measuring the properties of supernova explosions. They tell us how galaxies are moving away from us. In the next few years, we are going to gain a lot more insight into the nature of dark energy, whether it changes over time, and if it was constant over the whole course of history.

These are the pretty vital questions to address and I think that we are going to start getting answers.”