We missed the whole thing

It was a wondrous opportunity to be part of something historical. We just had a hard time comprehending what it would mean to other people, what it would mean to ourselves.

– Buzz Aldrin

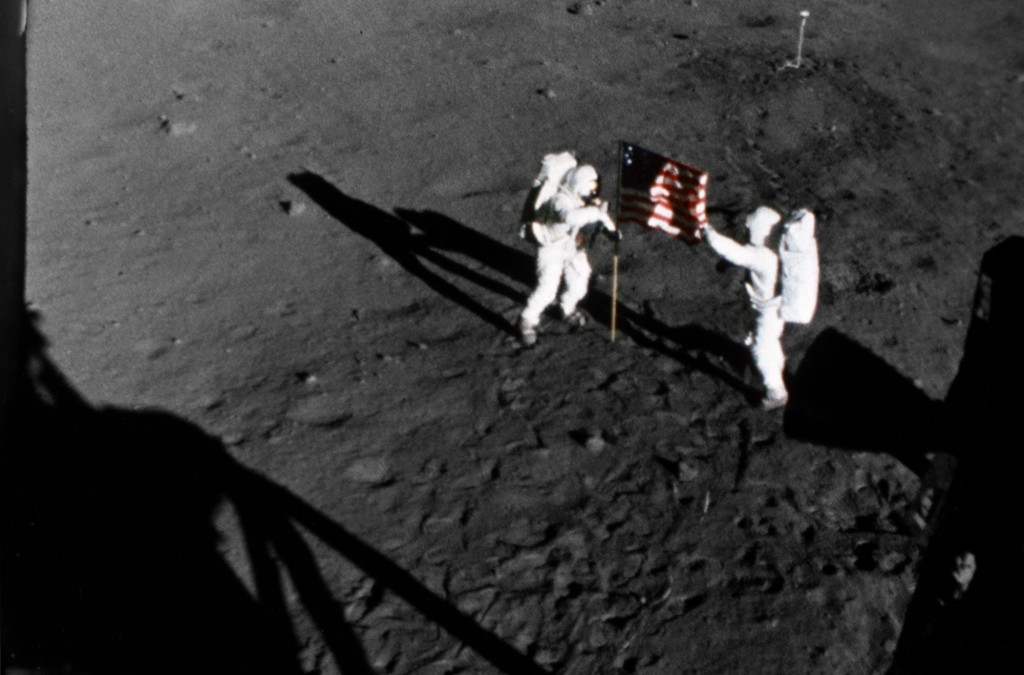

It was too much for us to grasp at the time. America was in hot battles at home and in cold wars abroad. Our campuses were in turmoil, our cities on fire. Our sons and brothers were in a war that divided our families and generations. Space travel was new, visionary, and dangerous, and we understood that for all its romance, the race to the Moon was yet another front like Berlin or Cuba in a struggle that made us do duck-and-cover drills under our schooldesks. Whatever winning was, we had to do it. And in the midst of all of that fear and fatalism, we saw the Earth whole for the first time, little and alone in the black of space, and two Americans stood on another world and said, “We came in peace for all mankind.” We were seeing our world as it might be, not as we had let it become.

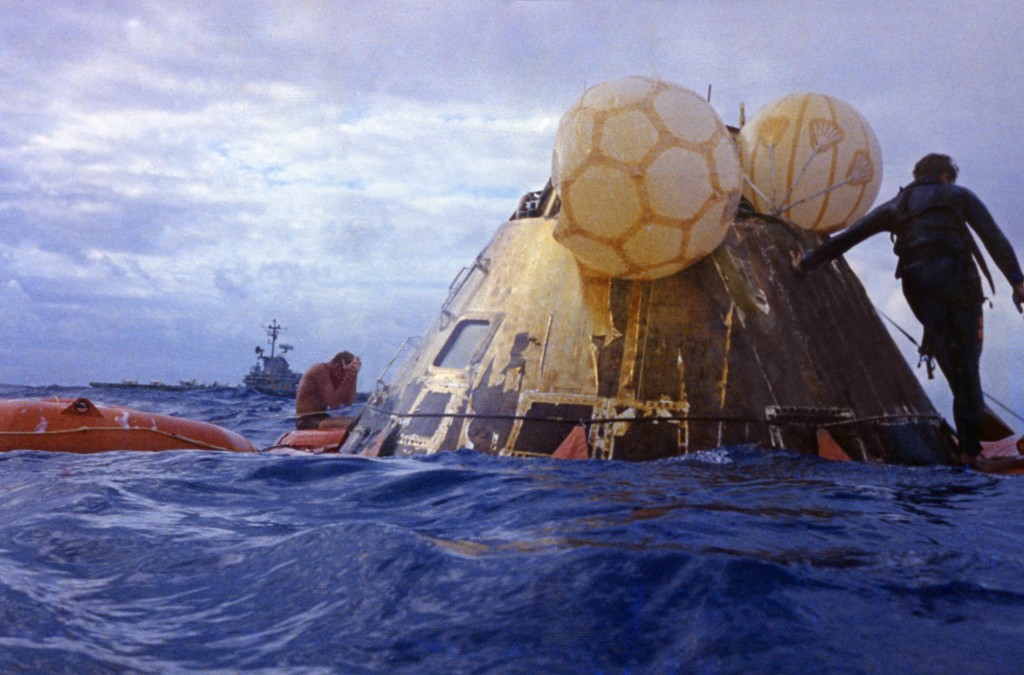

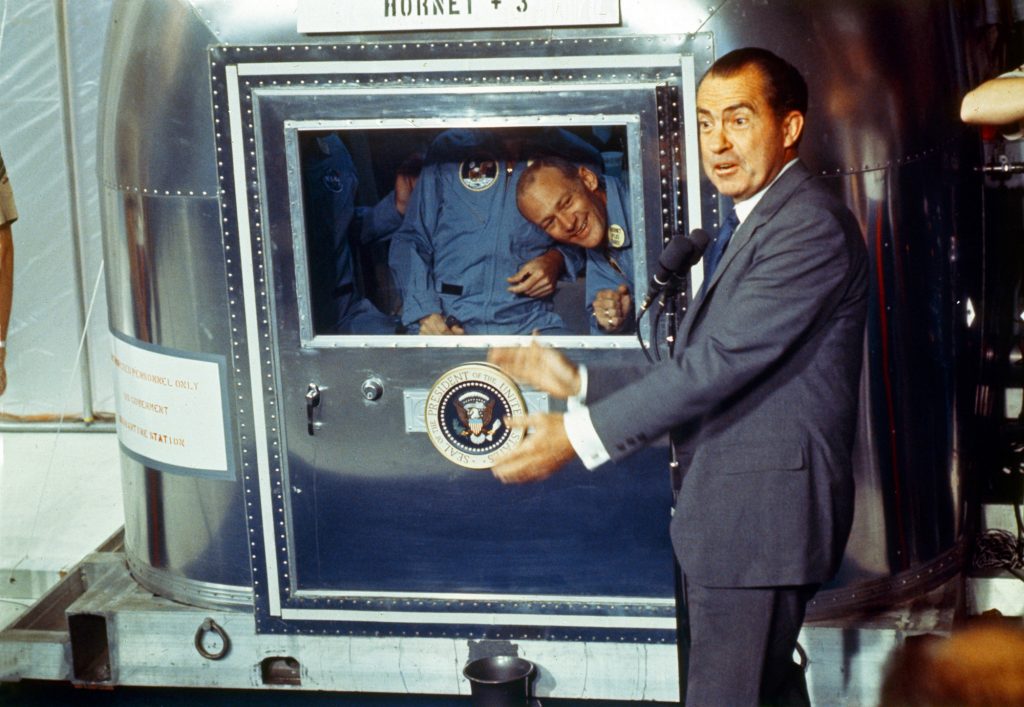

None of us could have been ready for it, not the ones who did it or those who witnessed it. Buzz Aldrin had a knack for capturing the feeling in succinct phrases like “magnificent desolation.” Perhaps his best characterization of it came after splashdown, when he realized the immensity of the world’s attention on Apollo 11, and saw that while he and his colleagues had been focused on deploying experiments, taking photos, collecting samples and making observations about the immediate, (“109:46:08 Aldrin: There’s absolutely no crater there at all from the engine”) hundreds of millions of people felt their lives changed in way they could not explain. “Neil,” he told Armstrong, “We missed the whole thing.”

We might still be missing it.

Armstrong and Aldrin had precious little time to spend on the grandeur of the place and the significance of the moment. Their heirs have had decades to weigh it all, and even with all this time, it remains irresistibly tempting for us to lose ourselves in the details. We can still be enthralled by the minutiae of acronyms and schematics. As years pass, the primary sources fade into archives; the facts get dramatized and mythologized; the people who did all this become heroes having sought only to be good at their jobs; and those of us most devoted to the real history of Apollo 11 can become merely the curators of specifics. We can spot a forged Armstrong autograph. We can explain a 1201 alarm, and navigate the meaning of “Mode Control, both Auto. Descent Engine Command Override, off. Engine Arm, off. 413 is IN” as though we are there now, much like the re-enactors with perfect reproductions of Civil War arms and uniforms can stand at the Bloody Angle at Gettysburg and tell visitors about Alonzo Cushing and Lewis Armistead. Retelling the old stories is irresistible, but the risk is the same one the crew of Eagle faced: missing the big picture, missing the reasons for it and the meaning of it while we focus on the tasks at hand; missing the whole thing.

Those of us who were lucky enough to have seen Apollo 11, and who remain privileged to shepherd its memory, might, as Americans, think of ourselves as part of the “we” who were first the Moon and of the “we” who came in peace. But we were observers, not participants. We watched it, we supported it, but we didn’t make it happen. A tiny sliver of Americans were involved hands-on. It was theirs.

Ours is what remains unfinished in the mission.

The generation before us went to the Moon. We have not been back since they did it. If “we” want to lay claim to the achievements and the legacy of Apollo 11 and to be part of something historical, let us deliver more than our memory for details. We are the spinoffs. We are the inheritors of the potential of Apollo. It fell to us to create the future of manned lunar exploration, and not just to witness it executed by someone else. The momentum flagged on our watch, but the questions raise fifty years ago still give us a galvanizing agenda, if we can take it. What ongoing steps of manned lunar exploration will best advance the first one? What can we do with what our predecessors learned? What does it mean to be multiplanetary humans? Can there really be such a thing on this divided world as “all mankind,” and can we rediscover that inspiration?

In viewing these iconic photos again, keep a quote from Buzz Aldrin in mind. It is not something he said on the Moon. He said it later, reflecting on what happened and on what happens next:

“Something is useless only if we do not know how to use it. If we use our Moon experience wisely in the years to come, there is no doubt that it will be a vital basis for greatly expanding our knowledge of the universe.”

Apollo changed nothing if we decline to live the change. The whole thing is yet to be fulfilled. Neil Armstrong made one small step. The giant leap is for us to make.

The story above was authored by David Clow.

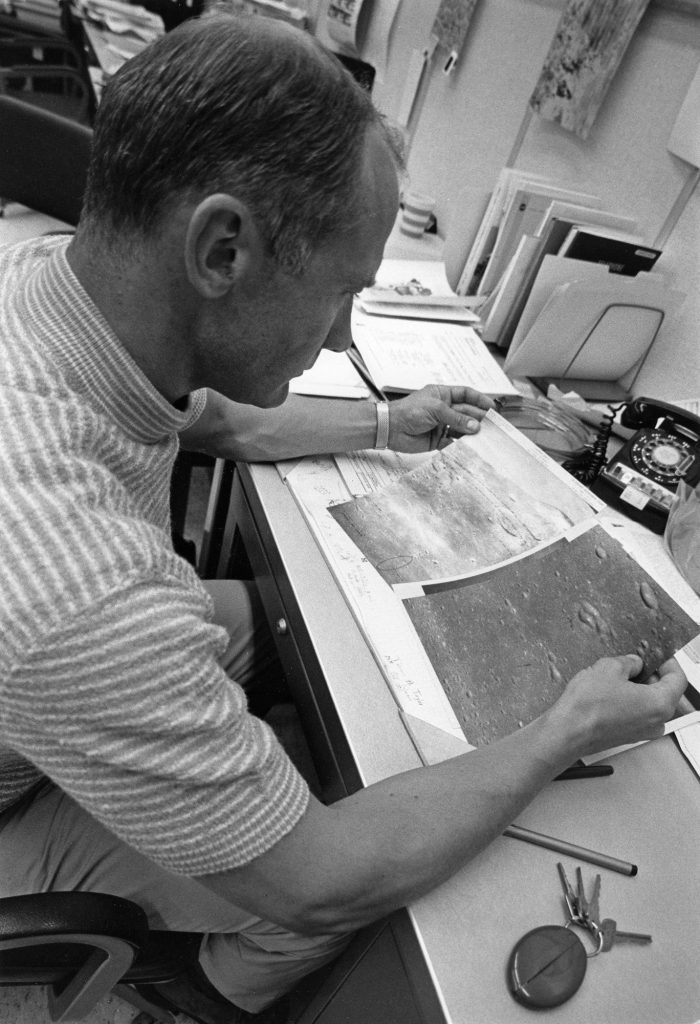

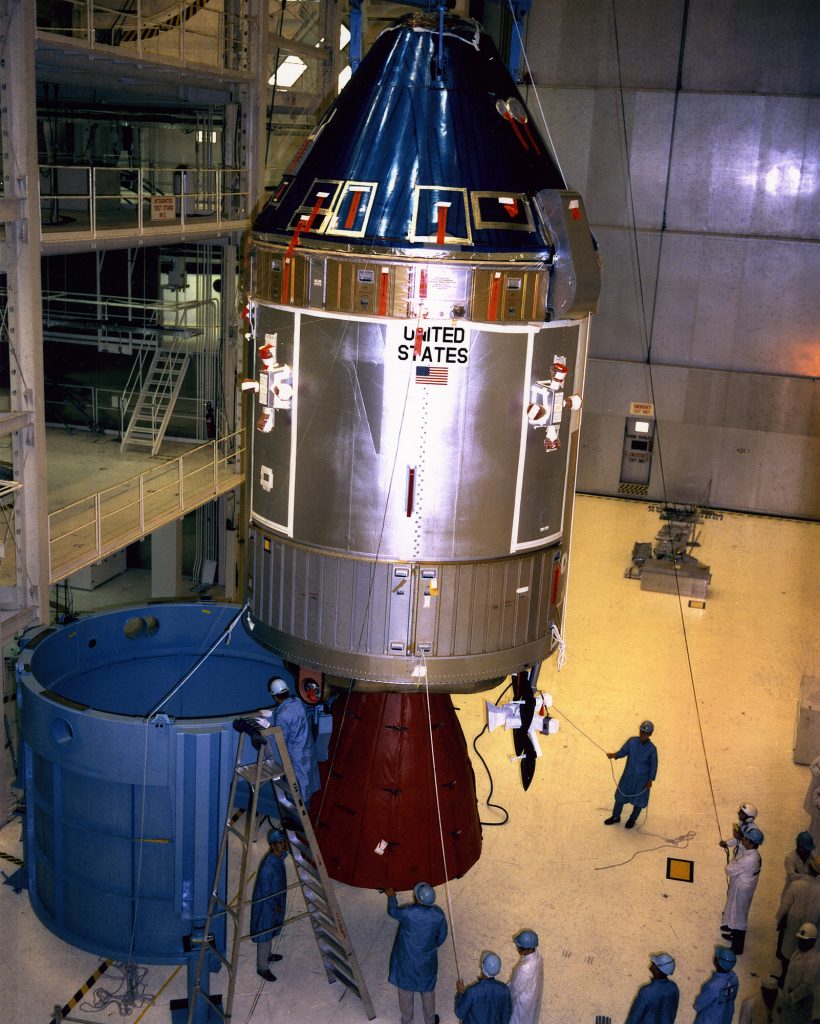

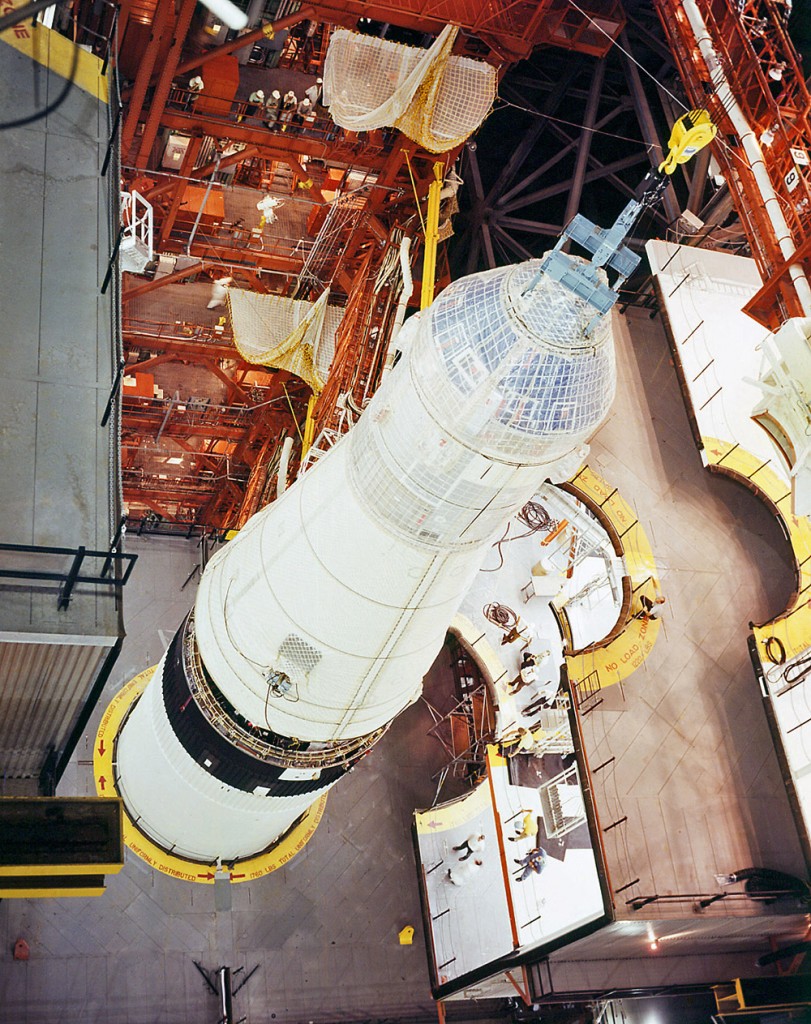

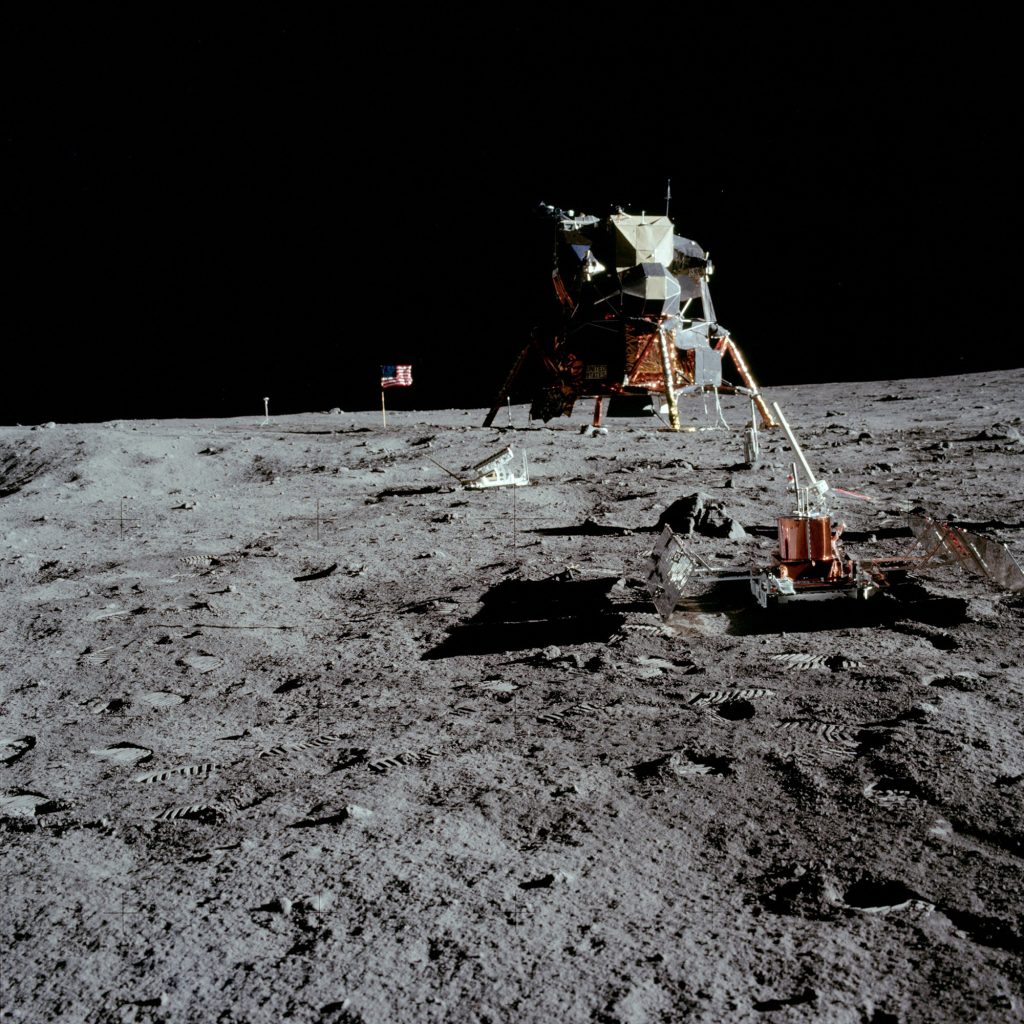

Following are some of the lesser known images from the Apollo 11 mission, as well as several stories from those involved with the historical program. Except where noted, the images were all provided by Retro Space Images and culled from NASA archives. Prepare for sensory overload, in 3…2…1.

In their own words:

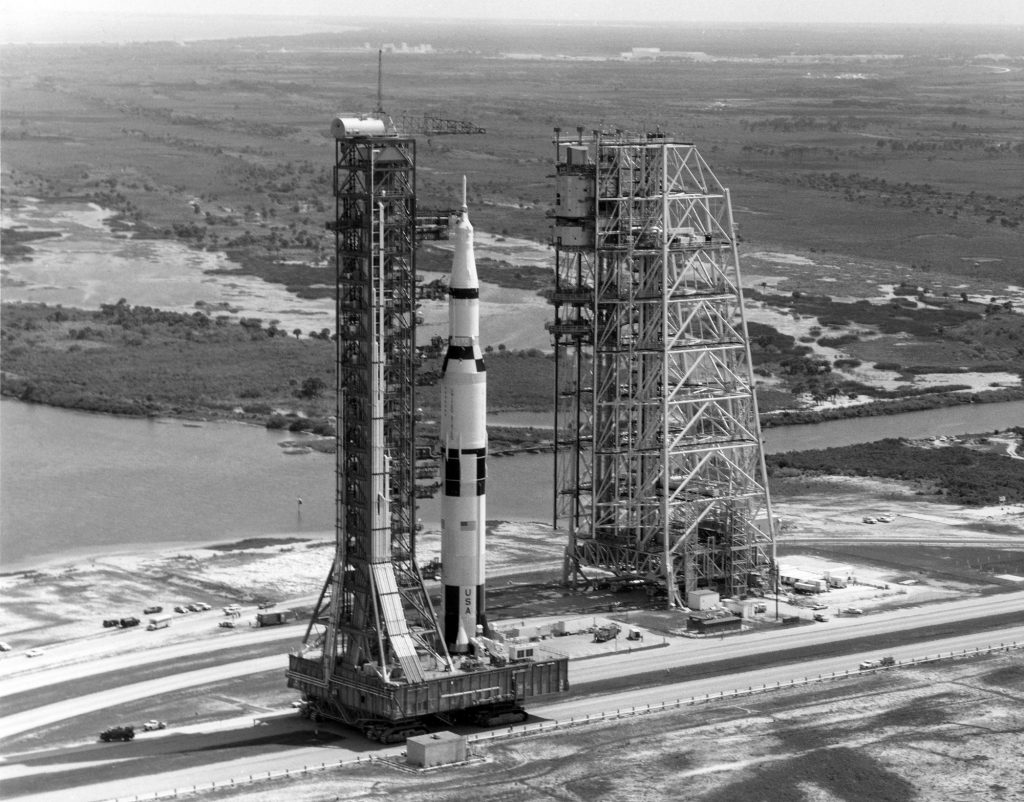

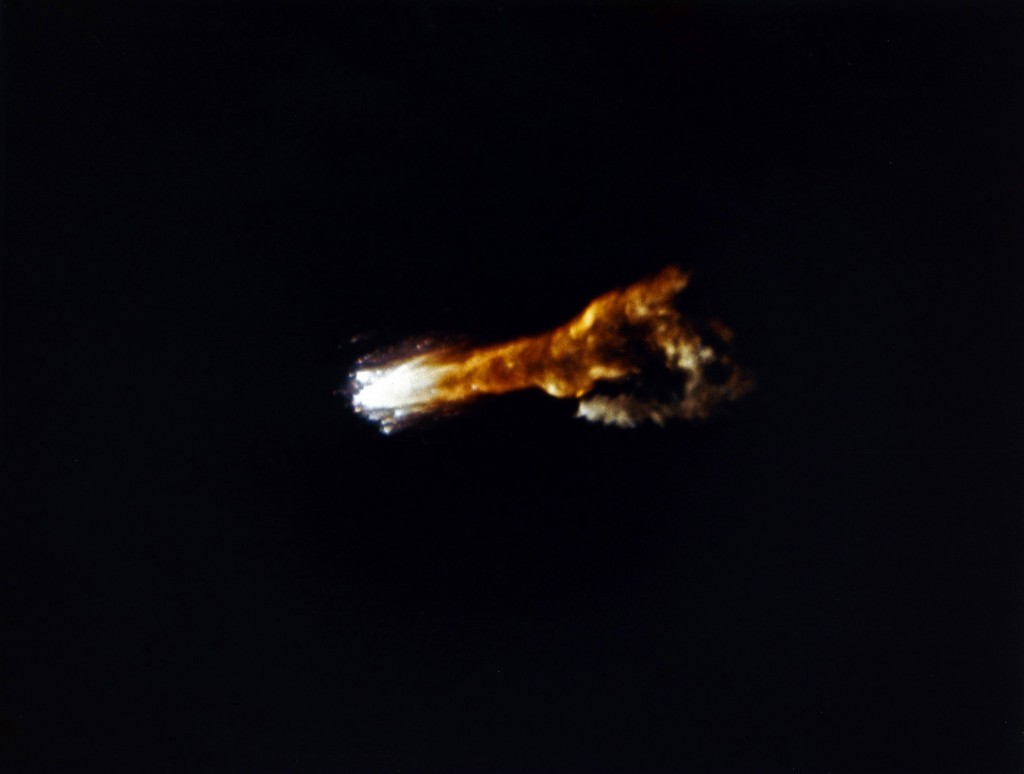

The rocket that rocked our world

Forty-five years ago a mammoth rocket and some pioneers of great vision helped humankind achieve a remarkable feat: walking on the moon. The event had a profound effect on those who witnessed it and created endless possibilities for those who came after.

Those of us old enough to have lived in Huntsville before NASA’s Apollo 11 moon mission can still recall the ground shaking as the mighty Saturn V first-stage rocket boosters, secured in a colossal test stand at nearby Marshall Space Flight Center, rumbled and roared. As the Earth trembled, we clung to our swing sets, paused our bicycles, jumped off our pogo sticks, and just stood still –mesmerized and amazed by what we knew was history in the making.

Soon after, the rest of the nation stood equally still – mesmerized and amazed as Neil Armstrong took his legendary “small step” on a distant world. A feat made possible by the same rocket.

It was one of those “transcendent moments of awe that change forever how we experience life and the world.”Although John Milton wasn’t speaking of the moment humankind set foot on the moon, his words aptly describe the profound effect events of such magnitude have upon those who witness them.

July 20 marks the 45th anniversary of the famous footstep – the result of a long and concerted effort by 400,000 NASA and contractor team members from across the country.

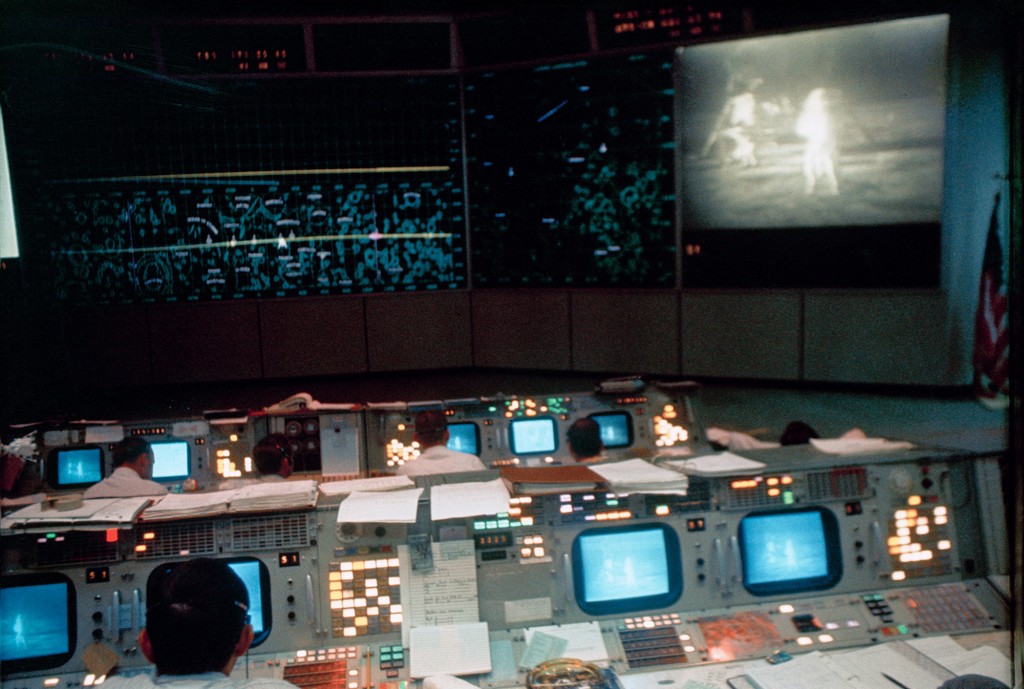

This incredible event inspired and uplifted the people who watched it unfold. Black-and-white televisions flashed patterns across darkened living rooms as viewers stared into the light at the almost surreal scene.

“I woke my two youngsters up to watch,” said Ed Buckbee, formerly of Marshall Public Affairs and the first director of the U.S. Space and Rocket Center. “They were half asleep on the couch – yawning, their eyelids drooping –but my eyes were open wide! I could hardly believe what I saw. We actually pulled it off – humankind walking on the moon! It was like something out of a science fiction novel.”

Ken Fernandez, who has worked at Marshall for more than 40 years, was 23 when the first moonwalk took place:

“The night of the moonwalk, I was in the Lake Guntersville campgrounds with a group from my church. We were watching the event on a portable TV plugged into my car. It was fairly late in the evening, but over 100 people from surrounding campsites gathered around our TV. Up on the moon, Armstrong came down a ladder and then stood on the lander’s pad. When he stepped off onto the lunar surface, there was a spontaneous cheer that was probably heard across the lake. It was one of those moments that you never forget.”

James Daniels, who worked for NASA from 1956 to 1981, attended the Apollo 11 Saturn V launch and then headed up to Fort Walton Beach for a brief respite.

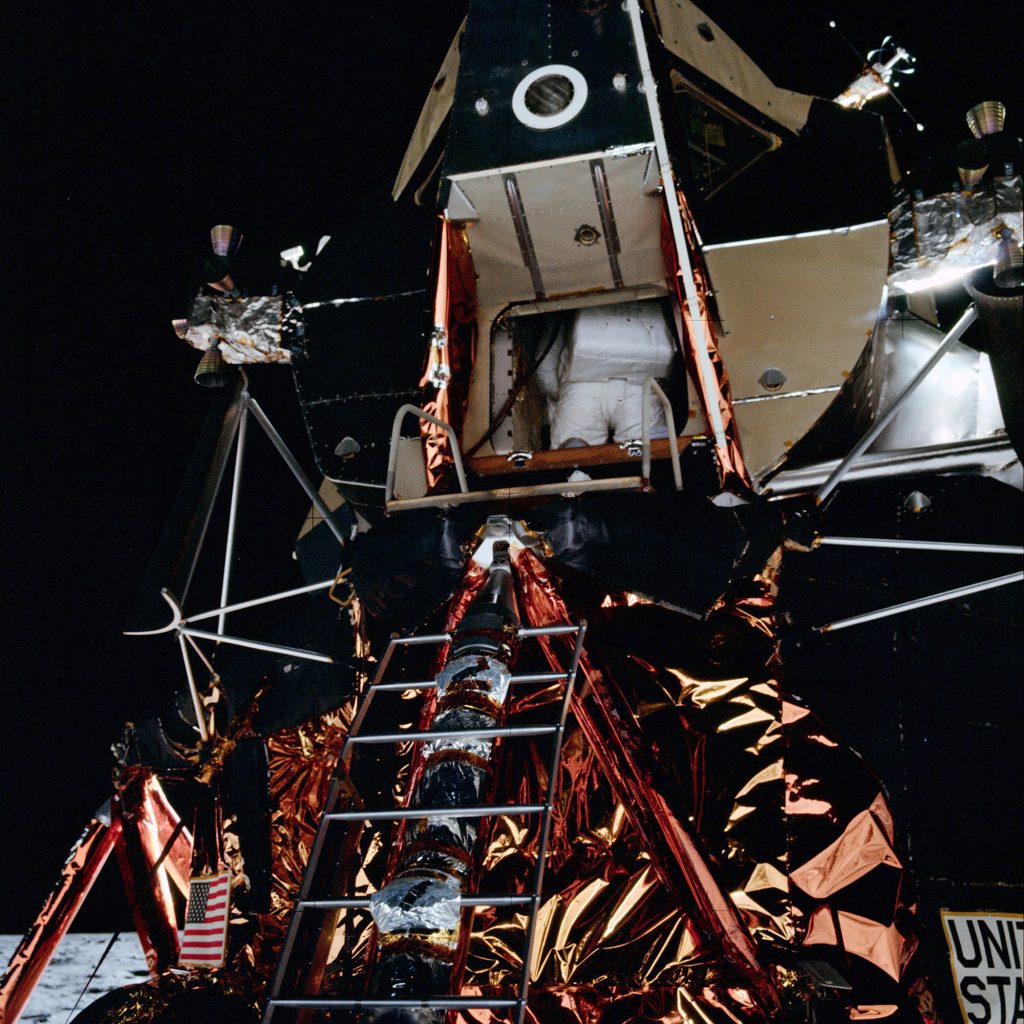

“I rented a room in a beachside apartment with a screened deck overlooking the Gulf. I put a little black-and-white TV out on the deck and watched most of the moon voyage coverage. I watched all during the late afternoon and early night of landing day. I was so relaxed by the Apollo landing time, which was late night at Fort Walton, that I dozed off in my chair in front the TV with the sounds of the ocean waves lapping the beach in the night. Fortunately, I awakened as Armstrong began his exit from the Lunar Module. I sat entranced by the ghostly glare of Armstrong’s space suit while he backed down the ladder in the darkened shadows of the vehicle and dropped off the last rung.

“When he uttered, ‘That’s one small step for a man, and a giant leap for mankind,’ I cried. My thoughts reeled at his words, which so well captured the event’s historic importance to us all.”

The Saturn V, the rocket that made it all possible, was designed at Marshall under the direction of Dr. Wernher von Braun. Bob Ward, the Huntsville Times’ first full-time space and missile reporter from 1962 to1966 and then Sunday editor, later wrote a book about the famous rocket scientist. And in 1969, he couldn’t resist stepping back into his reporter shoes to cover the big story.

“For old times’ sake, I assigned myself to Cape Canaveral in July 1969 to help cover the Apollo 11 launch. At NASA’s press site shortly after liftoff, I was sitting up in the press bleachers tapping out my story on an old typewriter when I suddenly spotted Dr. Ernst Stuhlinger leading an elderly gentleman whom I recognized through the crowd below. I hurried down from the bleachers and intercepted the pair. Amid the swirl of people moving about, I asked Stuhlinger if he would introduce me to his companion, Dr. Hermann Oberth, first space mentor to a teen-aged Wernher von Braun in Germany.

“With Stuhlinger translating, I interviewed the 75-year-old space pioneer –one of the founding fathers of rocketry and modern astronautics. Oberth found the Apollo 11 launch ‘even more exciting’ than he had dreamt as a boy. He said that NASA must press on and ‘undertake a manned Mars mission.’ It struck me as so very fitting that Professor Oberth should be present for this epochal mission to the moon.”

Fitting indeed. Twelve years before the launch, Oberth had written these words in his book Man Into Space:

“This is the goal: To make available for life every place where life is possible. To make inhabitable all worlds as yet uninhabitable and all life purposeful.”

Forty years ago, a big rocket rocked our world by helping a human step forth onto another world.

“Shall we follow…?” (from T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, Burnt Norton)

The story above was authored by Dauna Coulter.

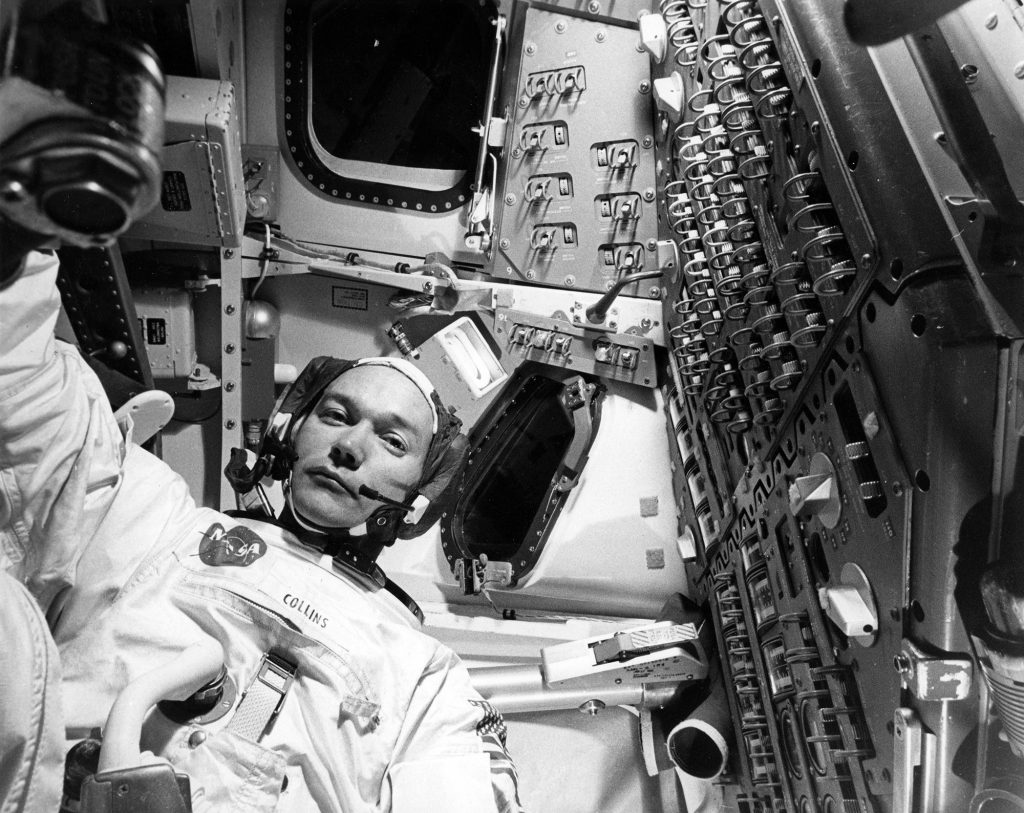

It’s human nature to stretch, to go, to see, to understand. Exploration is not a choice, really; it’s an imperative.

– Michael Collins

In their own words:

Kicking up the dust and everything

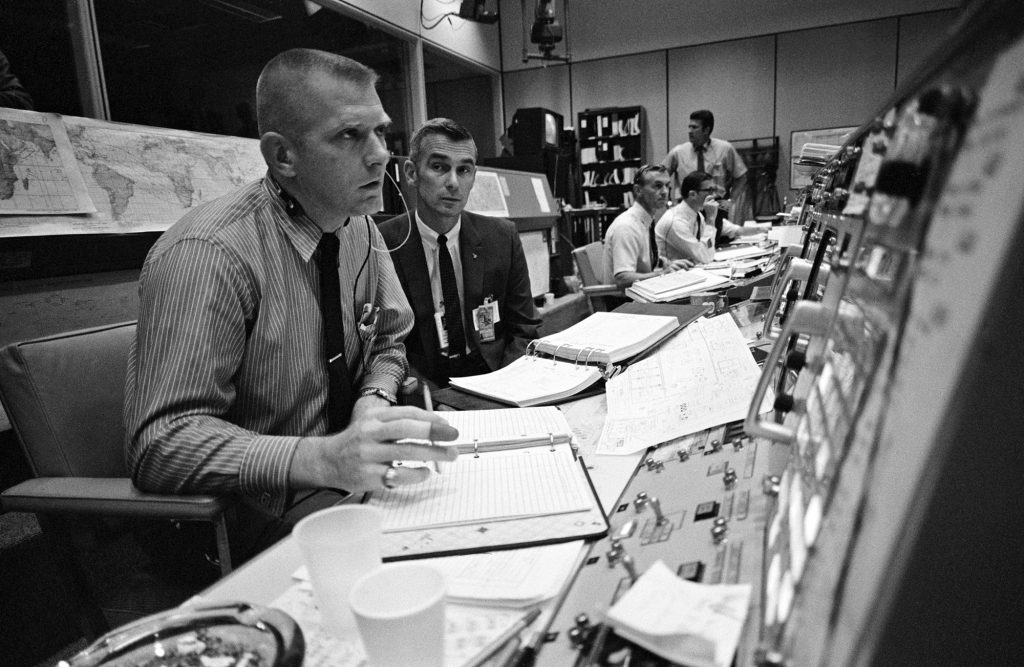

As chief of public affairs for the Manned Spacecraft Center, Paul Haney was known as the “Voice of Mission Control” for the Gemini and first four manned Apollo flights. In 1969, he left NASA to report on space missions for ITN (Independent Television News) in London. The astronauts were his friends, and he understood spaceflight procedures. He recalled his thoughts as the Apollo 11 lunar module was trying to land on the Moon.

When the 1201 emergency [computer] alarm was sounded, I was just listening to that as they came down [for lunar landing]. I knew that was an abort parameter and, boy, I took a bunch of breaths. Then I remember it was [Buzz] Aldrin saying, “Just ignore that.” He said that very quickly. And he did one hell of a job calling the landings. If you listen to that tape, he was busy. Charlie Duke was capsule communicator. After the landing, he said something like, “We’re all about to turn blue down here,” which was a pretty honest reaction. They had something like three or four seconds worth of fuel left in the descent tank. You couldn’t cut it any closer. But Neil seemed to know what he was about, kicking up the dust and everything. That was really hairy, I thought. What if the lift-off rocket doesn’t work in the LM? There was no backup. There was just one way to get out of there. It had to work, and that was the piece that was developed at White Sands, Las Cruces. They fired that thing up how many hundreds of times, and it worked real well. It had one hell of a success record. It worked six times on the Moon, too.

This is an excerpt from the book, “Space Pioneers: In Their Own Words” which was authored by Loretta Hall and released last month. The book is available for purchase at www.amazon.com.

Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.

– Neil Armstrong

That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.

– Neil Armstrong

In their own words:

Tears in the middle of the night

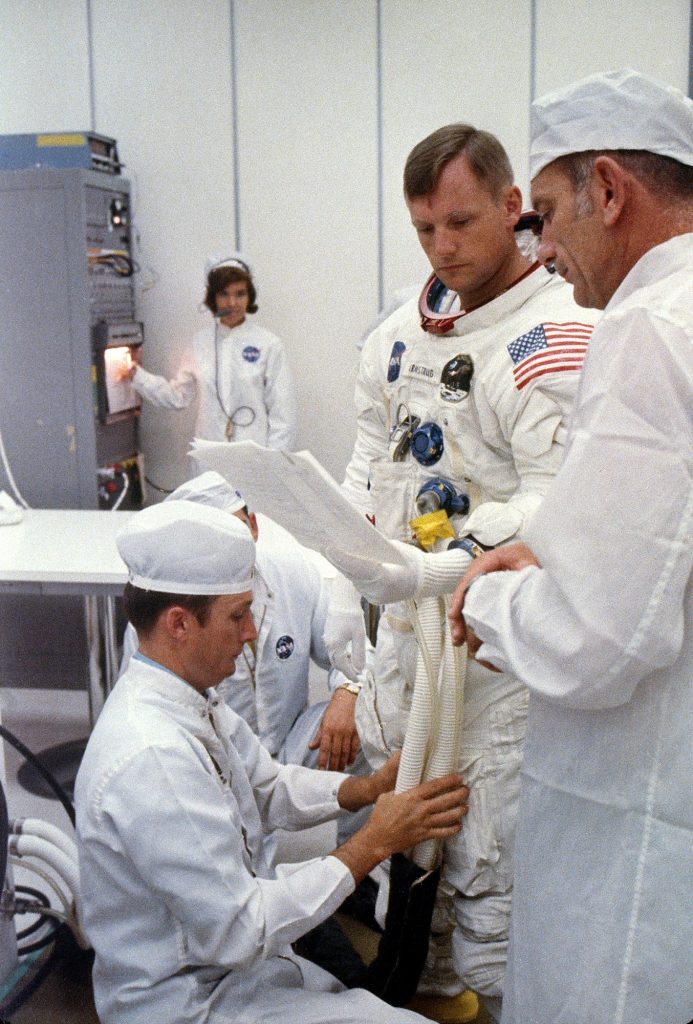

Skip Chauvin was a spacecraft test conductor for every one of the Apollo missions, overseeing the closeout crew on the day of launch for Apollo 11.

Things were going so fast in those days that, all the way through countdown, I never felt a big rush, like oh my god, oh my god, i’m nervous and can’t do this. I suppose in retrospect I should have been surprised that I wasn’t all nervous and uptight. But it just rolled on. We had done several before that, and I think we were all so anxious to each do our parts to the best of our abilities, that none of us seemed to be all excited.

The crazy part about it is, after liftoff, once we were sure things were OK, I packed up my family – three kids and my wife – and the boat and we took off south to Lake Worth down in southern Florida. So all during that time it was busy, busy, but when it came time for the landing itself on the Moon, I remember it was the middle of the night and all the family was asleep. I had the TV on and the sound down low and when it finally came time, you know, “The Eagle has landed,” I started crying. All by myself there with everyone else asleep. And I started crying.

It just built up inside me I guess and it all came out at that point. Tears were streaming down my face and I guess I said to myself, “Oh my god we did it.’ I say ‘we’ as a great many people that I worked with and others across the country contributed so much in every facet of the game. It all came together, and that is what I remember most about the lunar landing.

Here Men From The Planet Earth First Set Foot Upon the Moon, July 1969 A.D. We Came in Peace For All Mankind.

The biggest benefit of Apollo was the inspiration it gave to a growing generation to get into science and aerospace.

– Buzz Aldrin

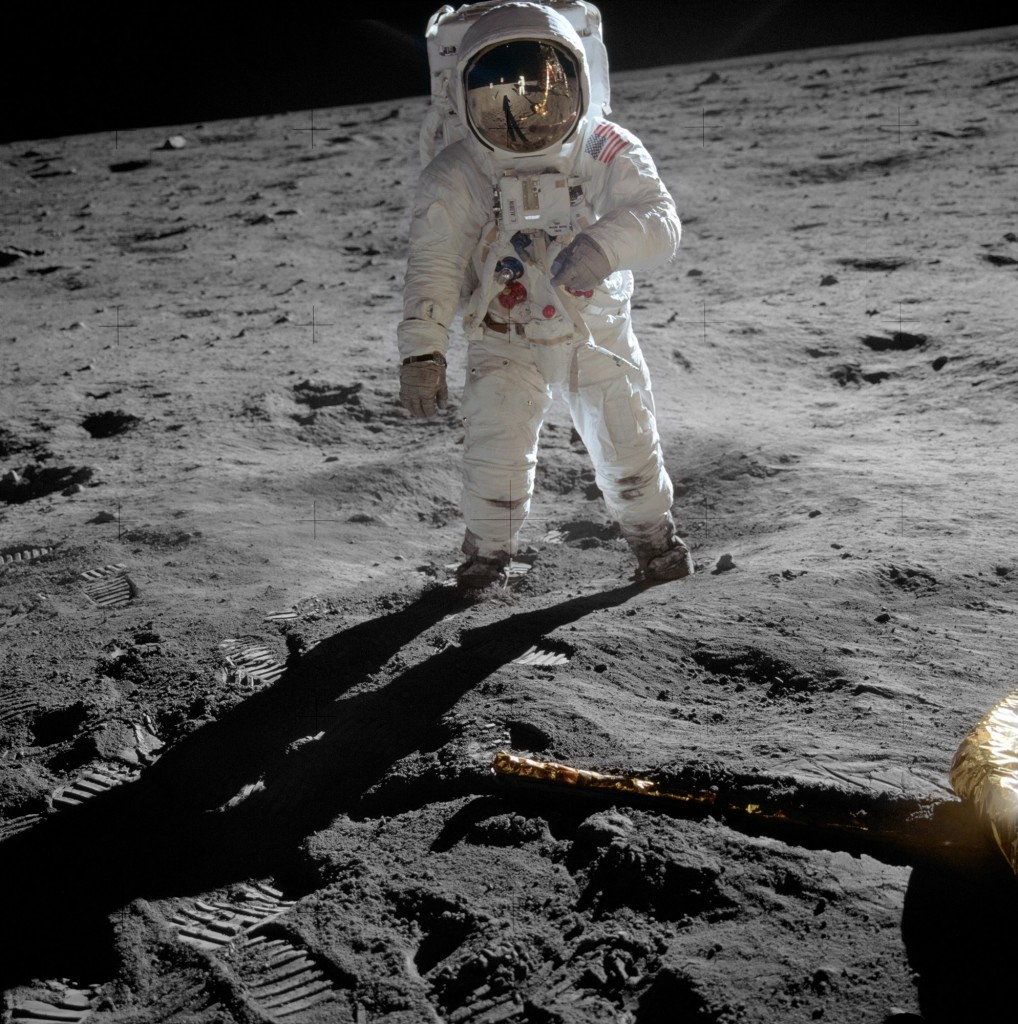

Magnificent desolation

– Buzz Aldrin

In their own words:

A change of plans

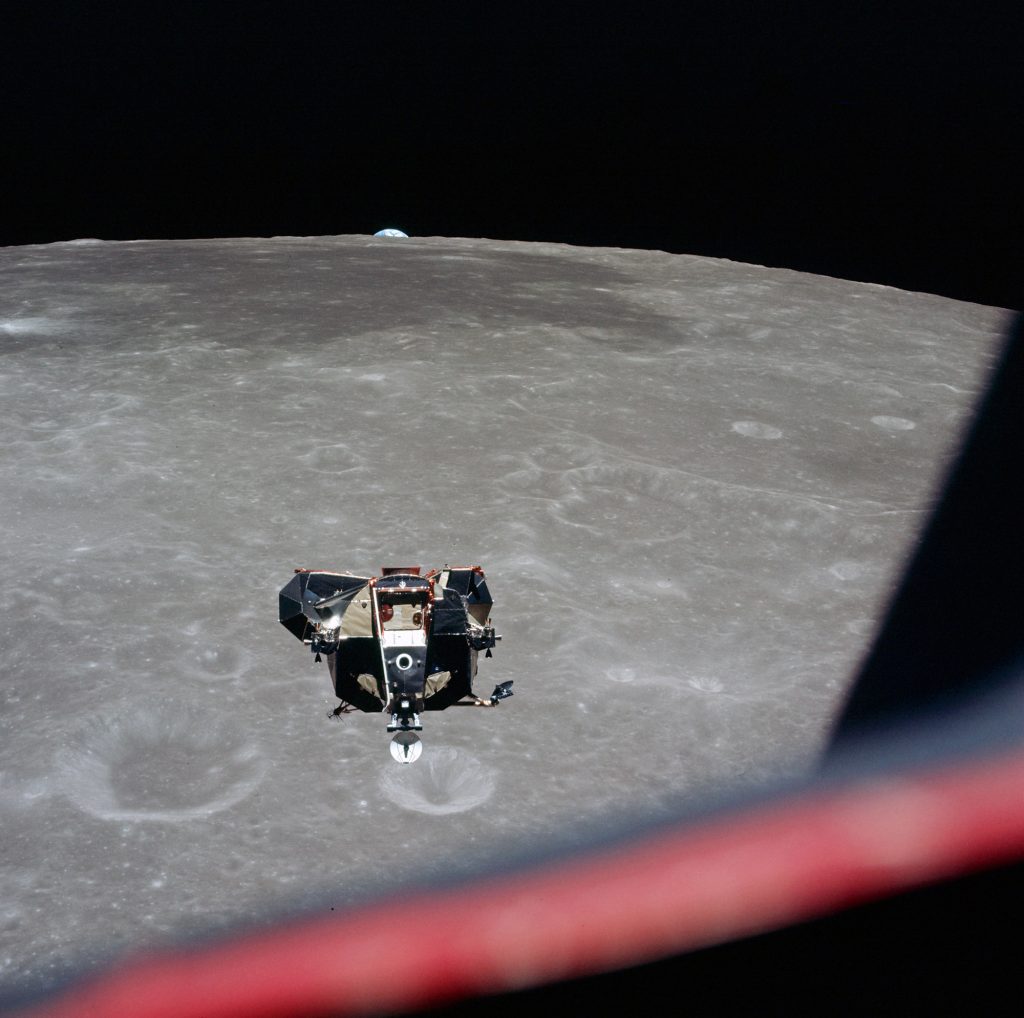

As retrofire officer for Apollo 11, Charles Deiterich was in charge of planning and monitoring the maneuvers to remove the command module from lunar orbit and head it back toward Earth. He recalled an unplanned schedule change after the lunar module (LM) lifted off from the moon and rejoined the command module in lunar orbit.

On Apollo 11, once you get all the rocks and stuff out and close out the LM, you really don’t want to hang around it. They had another rev to go before they were going to close the hatch. Well, they come around the corner [from the back side of the Moon] and the hatch was already closed. We go, hey, we don’t really want to stay on this thing, because it’s got the engine with things armed, and it’s ready to do stuff. So we had to separate one rev early. We would deorbit that thing out of lunar orbit, and then we’d check the seismometers from the ground on the Moon’s surface.

This is an excerpt from the book, “Space Pioneers: In Their Own Words” which was authored by Loretta Hall and released last month. The book is available for purchase at www.amazon.com.

The important achievement of Apollo was demonstrating that humanity is not forever chained to this planet and our visions go rather further than that and our opportunities are unlimited.

– Neil Armstrong

When the history of our galaxy is written, and for all any of us know it may already have been, if Earth gets mentioned at all it won’t be because its inhabitants visited their own moon. That first step, like a newborn’s cry, would be automatically assumed. What would be worth recording is what kind of civilization we earthlings created and whether or not we ventured out to other parts of the galaxy.

– Michael Collins

Sources

- Robert Block, Sentinel Space Editor. “EXCLUSIVE: Q & A with Buzz Aldrin. Apollo 11: 40 years later.” Orlando Sentinel. July 19, 2009. http://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/local/lake/orl-buzz-aldrin-interview-071909,0,4473935.story.

- Eric M. Jones, “One Small Step.” Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. http://www.hq.nasa.gov/alsj/a11/a11.html.

- Andrew Chaikin and the Editors of Time-Life Books. A Man on the Moon. Vol. I,. One Giant Leap. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books. 1999.

- Return to Earth. Colonel Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr., with Wayne Warga. New York: Random House. 1973.

- Retro Space Images, https://retrospaceimages.com

Loretta Hall, Dauna Coulter, Paul Haney, Skip Chauvin and Charles Deiterich contributed to this article.