Anyone who has witnessed a Space Shuttle or rocket launch in person from Cape Canaveral, Florida has probably seen the Pave Hawk helicopters patrolling up and down the coast in the hours before launch. The airmen onboard serve a critical role for every launch – providing safety and security surveillance to the Eastern Launch Range. Simply put, if they do not secure the range, rockets do not launch.

The 920th Rescue Wing, based out of Patrick Air Force Base, serves as an Air Force Reserve Command combat-search-and-rescue unit. They are responsible for a variety of demanding missions, ready to deploy at a moments notice, and trained to perform some of the most highly specialized operations in the Air Force.

They were the primary rescue force serving as “guardians of the astronauts” for 50 years, providing contingency response for a variety of emergencies that could potentially come up during a Space Shuttle launch or landing. These airmen and their elite team of Pararescuemen, known as PJs, are among the most highly trained emergency trauma specialists in the U.S. military, capable of performing life-saving missions anywhere in the world, at any time.

In addition to combat search and rescue operations, the 920th also provides search and rescue support for civilians at sea who are lost or in distress, as well as providing worldwide humanitarian and disaster-relief operations supporting rescue efforts in the aftermath of disasters such as earthquakes, floods, and hurricanes. When a covert four-man Navy SEAL team was ambushed and surrounded in a Taliban counter attack high in the Hindu Kush mountains of Afghanistan in the summer of 2005, the 920th is who they called for rescue.

In the spring of 2012, I was invited by the 920th to fly along on a range-clearing mission to support the historic launch of the first SpaceX Dragon spacecraft to the International Space Station. The mission, known as COTS-2, was the first to see a commercial company deliver supplies to the orbiting outpost, which orbits some 250 miles above Earth. No photojournalist had ever flown with the 920th for any launch since they began supporting the U.S. Space Program in 1961, I was the first, and I was very humbled for the opportunity.

Although America’s human spaceflight program is currently 100% dependent on Russia since the retirement of NASA’s Space Shuttle program, the 920th’s role supporting unmanned rocket launches from the Cape is still as active, and as important, as it has ever been.

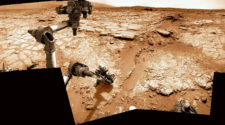

of the SpaceX Falcon 9 COTS-2 launch. Credit: Mike Killian

Hawks & Falcons

Crews take to the skies in one of the most sophisticated helicopters in the world, the HH-60G Pave Hawk, a “Black Hawk on steroids” according to Captain Cathleen Snow, Chief of Public Affairs for the 920th Rescue Wing. They feature an upgraded communications and navigation suite that includes integrated inertial navigation/global positioning/Doppler navigation systems, and satellite communications. They are also equipped with an automatic flight control system, night vision, and a forward looking infrared system – known as color radar – that greatly enhances night low-level operations and allows them to fly in virtually any weather, day or night.

Many of the Pave Hawks flown by the 920th still have bullet holes from their tours in Afghanistan and Iraq, a sobering reminder of the reality of their jobs as combat-search-and-rescue airmen.

I arrived at Patrick AFB at 12:30 a.m. May 19 for our flight supporting the first launch attempt. After security checks, I proceeded to go meet the crew and conduct the standard pre-flight briefing. The briefing is incredibly thorough, nothing is missed, everything from contingency plans in case of an emergency, to radio frequencies, to the positions of both Pave Hawks at launch time is covered.

Both Pave Hawk crews were also brought up to speed on the launch itself and the details of the COTS-2 mission, and they were not shy about showing their excitement for a one-second launch window as opposed to a typical two- or three-hour launch window. Our Pave Hawk would patrol north of the launch site, call sign Jolly 1. The other (Jolly 2) would patrol to the south of the launch site.

Once everyone was briefed it was time to put on our flight gear and life support equipment. The building where we geared up, at first glance, resembles a locker room at any gym, except instead of football helmets and dirty socks there are night vision goggles, parachutes, flight helmets and headsets, inflatable military life preservers, and probably a few pairs of dirty socks. We geared up and made sure our headsets worked properly, then walked to the flight line, where two of Patrick’s 14 Pave Hawks were being prepared for our mission.

After talking with the crew and going over emergency scenarios, such as learning how to safely bail out of a Pave Hawk, the APUs started and the choppers came alive. Our pilot was Colonel Jeffrey “SKINNY” Macrander, who just so happens to be the Commander of the 920th Rescue Wing – responsible for the management and supervision of some 1,700 citizen airmen under his command. A veteran of Operations Allied Force, Northern Watch, Noble Eagle, Southern Watch and Operation Enduring Freedom, Colonel Macrander is a rated command pilot and has over 4,500 hours of flight time in five different military aircraft. He was also part of the crew who rescued ambushed Navy SEALS in the Afghan mountains in 2005.

“They usually like us to clear the box about two hours prior to launch. Since it is 2:00 a.m. we don’t expect a whole lot of small boats out there, but we still get the commercial traffic that cruises back and forth,” said Col. Macrander minutes before our flight. “The big boats are always up on a maritime frequency, so we have a special radio in the Pave Hawk to call and talk to the boats. We’ll tell them to either speed up, change their course, or slow down so that they are not in the range for the launch window. We’ll call the coordinates into the control office at the Cape and they will plot it, do some math, and let us know what the boaters need to do to stay out of the range. A lot of times the small boats are just fishing and not monitoring their radios, so sometimes we have to come down there and hover pretty close to get their attention and let them know with hand gestures to get on the radio.”

I would find out later that evening just how close they get to those small fishing boats not paying attention to their radios. We even hovered within 200 feet of a boater who was sound asleep, using the noise from the rotors and flashing bright spotlights on his boat to wake him up. I can only imagine his reaction, waking up to an Air Force Pave Hawk circling him in the middle of the night.

As for the launch, it scrubbed 0.5 seconds before liftoff. A second launch attempt was scheduled for three days later. In the meantime I had a different assignment on the other side of the country, but was already looking forward to my flight for launch attempt number two.

Dragon’s Breath

I returned Monday night, May 21, at 10:30 p.m. to do it all over again, but this time with Lt. Colonel Rob Haston piloting our Pave Hawk. Lt. Colonel Haston has been supporting rocket launches for nearly twenty years, piloting Pave Hawks and clearing the range for nearly every launch since 1995 – including Space Shuttle launches and landings. He has witnessed three rockets explode, so he understands first hand the importance of the 920th’s role in securing the Eastern Range for a launch.

“I liken supporting rocket launches to fishing. There are a lot of nuances to range clearing that I’ve experienced over the years,” said Lt. Col. Haston. “You get to know the type of boats and generally where they are going. A lot of different skills are involved depending on the type of boats you are dealing with. You may be dealing with a 1,000-foot freighter with a non-English speaking captain, or a brand new boat owner in a sailboat.” Lt. Col. Haston’s unique experience supporting launches is, as he put it, “not the sort of thing you pick up in Air Force regulations,” but rather tricks of the trade.

We went through the same routine as we did for the first launch attempt, but this time the crew gave me a pair of night-vision goggles so I could see what they see and shoot some photos to give viewers their perspective. The night vision goggles help amplify the available light from the Moon and stars by up to 5,000 times onto a green phosphorous screen; the human eye can distinguish more shades of green than any other color. There was no moon this night, and even 60 miles out over the ocean in the darkest black I have ever seen, the goggles illuminated everything, I could even see the ripple of waves on the ocean’s surface.

We took to the skies two hours before launch, heading up the coast of Brevard County towards Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, where SpaceX Launch Complex 40 and their Falcon 9 rocket stood fully fueled. We hovered a short distance away from the rocket for a few minutes, allowing me to shoot some exclusive photos from our unique vantage point before heading out to sea to clear boat traffic off the range. Our orders were to clear an area about 20 miles wide and 60 miles long around the launch site.

“They (range control) want us to clear 8-10 miles away from the azimuth. With a small rocket like this, it’s a small box, but because it’s brand new we need to keep it pretty clear,” said Lt. Col. Haston.

The night was fairly quiet, there was not much boat traffic getting in the way, but it was interesting to come within a couple hundred feet of a Carnival cruise ship and tell them to hurry up and get into Port Canaveral before the launch. I can only imagine the surprise people onboard must have felt when they saw, or heard, us circling overhead.

Lights go off in the Pave Hawk during night-ops. Small fluorescent tubes reference our emergency exits, and the cockpit controls and displays – as well as the LCD screens on our cameras and cell phones – were the only lights we had. The pitch black view 60 miles out over the Atlantic allowed the Milky Way to shine brightly in the sky, and the sound of our rotors with no visual of anything was very strange, even eerie.

At one point I lost all reference of direction and could not even see the camera gear I had strapped to me.

Eventually the lights of Florida’s Space Coast began to shine, and the unmistakeable sight of xenon lights on the Falcon 9 rocket came back into view. Even from 30 miles out, on a dark moonless night, NASA’s massive Vehicle Assembly Building stood out like a sore thumb – many of my friends and colleagues were on the roof to cover the historic launch.

We arrived at the shoreline north of Kennedy Space Center about 20 minutes before launch, at which point we headed south along the beach, over Apollo/Shuttle launch pads 39B and 39A before hovering one final time next to the Falcon 9 for some last minute photos. We then proceeded to fly over KSC, at which point Lt. Col. Haston brought us over to the VAB, circling it from the back and bringing us within throwing distance of the rooftop and the press site. I could see some of the press corps flashing lights at us, their way of saying hello – we were close enough that I could see the light from the LCD screens on their cameras.

We positioned ourselves just north of the VAB and hovered with a great view of Falcon 9 out the left side of our Pave Hawk. We listened to the launch commentary on our headsets and watched in awe as the Falcon 9 roared to life under cover of darkness. The power of its nine Merlin engines turned night into day and the entire landscape of Kennedy Space Center lit up. The rocket and its Dragon spacecraft accelerated quickly through the atmosphere, vanishing as it climbed above the Pave Hawk’s rotors and out of view, at which point Lt. Col. Haston tilted us up so I could get in a few more shots. We then circled to try and position ourselves for another view, but by that time the rocket was already gone, still visible, but already on the edge of space en route to the International Space Station.

With that, our mission was complete, and we headed south back to Patrick. As we approached Port Canaveral, the first stage of the Falcon 9 was already re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere, shining as bright as a comet as it plunged back to Earth. Upon reaching the Port, Lt. Col. Haston decided to show me a little more of what the Pave Hawk could do, performing some maneuvers that most would describe as a roller coaster ride over Port Canaveral. I’m sure some of the folks on the ground wondered why a Pave Hawk was going crazy in the sky, but it sure was fun.

“Day launches are my preference as you encounter wildlife from the aircraft. You can see various fish, turtles and dolphins, and the occasional whale while flying over the wide open ocean,” said Lt. Col. Haston. “But supporting any landmark launch, like this one, is always a great thing to be a part of.”

Landing at Patrick was the end of my day, or night, depending on how you look at it. But for the crews I flew with, it was just the beginning, as they were getting ready to perform a search-and-rescue operation for a ship 1,200 miles off the coast of Florida in the area of Bermuda. Their motto, “These things we do, that others may live” is a way of life for the men and women of the 920th Rescue Wing, and I am honored to have flown with them, twice, to cover a launch which marked a pivotal turning point for America’s space program.

For more information on the 920th Rescue Wing, visit their website: www.920rqw.afrc.af.mil or follow them on Facebook: www.facebook.com/920thRescueWing.

Originally produced by Mike Killian for ARES Institute’s Zero-G News.